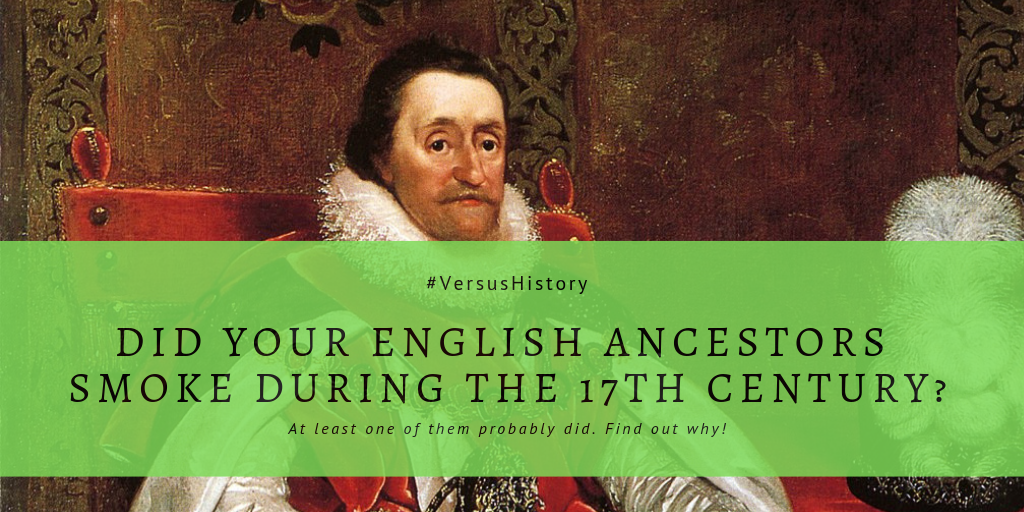

...THAT AT LEAST ONE OF YOUR ENGLISH ANCESTORS (PROBABLY) SMOKED IN THE 17TH CENTURY.Smoking tobacco is an addictive, dangerous and expensive habit. It can be potentially ruinous to the health of the smoker and those around them via the vehicle of passive smoking. In the UK, tobacco products cannot be advertised. Nor can they be visibly displayed on the shop floor of your local supermarket or convenience store. Needless to say, due to the ever-increasing public awareness about the negative health implications associated with tobacco smoke (and the relatively high cost of the tobacco products themselves), the number of people who regularly smoke in the UK is in a steady period of decline. However, if you have English ancestry dating back to the 17th century and the Stuart-era, then the chances are that at least one of them smoked tobacco imported from the Americas. Moreover, they may well have believed that tobacco was actually good for them! "In the late 16th- and 17th-century in England tobacco was thought to be a panacea that was universally good for the body." (Jennifer Evans, 2019, History Today) Tobacco was first imported to England during the Tudor period (pre-1603) from the Americas. When Queen Elizabeth I died in 1603, leaving no heir, the Scottish Protestant King James VI, was invited to become King James I of England. His reign witnessed many key historical events: the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 and the journey of the Pilgrim Fathers on the Mayflower to the 'New World' in 1620, to name but two. It also witnessed an exponential growth in the importation of tobacco products from the Americas to feed rising demand. Interestingly, King James actually detested smoking, while simultaneously craving the source of revenue that it raised for the coffers of the Crown: "A custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs, and in the black, stinking fume thereof, nearest resembling the horrible Stygian smoke of the pit that is bottomless." (King James I) Clearly, King James understood the dangers associated with this newly imported habit. When English colonists arrived in Virginia on the east coast of the modern United States of America in the very late 16th and early 17th century, the majority had hoped to 'strike it rich' by finding a bountiful supply of gold and precious metals. When no such find was readily forthcoming, the English colonists slowly but surely switched to tobacco as a source of revenue. The cultivation of the tobacco plant required a vast pool of labour to undertake the grim, repetitive and burdensome work on the plantations. Initially, white indentured labour was used, but this soon gave way to slave labour, with Africans being forced into service under horrific and barbaric conditions. As the number of English smokers during the Stuart-era grew, so the amount of tobacco produced and exported to England rose exponentially to satisfy the rising demand. "By 1670 half the adult male population of England used small pipes made from clay to smoke tobacco on a regular basis." (James Evans, 2018, Why the English Sailed to the New World) Given that in 1570 very few English people would have been exposed to the leaf that emitted the infamous 'stinking fume', this represents a significant growth amongst a population of just over 5 million people by 1650. Therefore, if you have English ancestry dating back to the Stuart-era, it is highly likely that at least one of your forefathers took up the habit of smoking between 1603 and 1714. To take this a step further, you may well have English ancestors that emigrated to the American colonies during this time to participate in the tobacco production process, either directly or by supplying its feeder industries. Approximately 10% of the English population left for the American colonies between 1600 and 1700. While a significant proportion of English migration to the American colonies at this time was fuelled by religious motives, for those such as the family of George Washington the provision of tobacco products to the mother country may have also been a significant financial incentive to make the 3000-mile journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

1 Comment

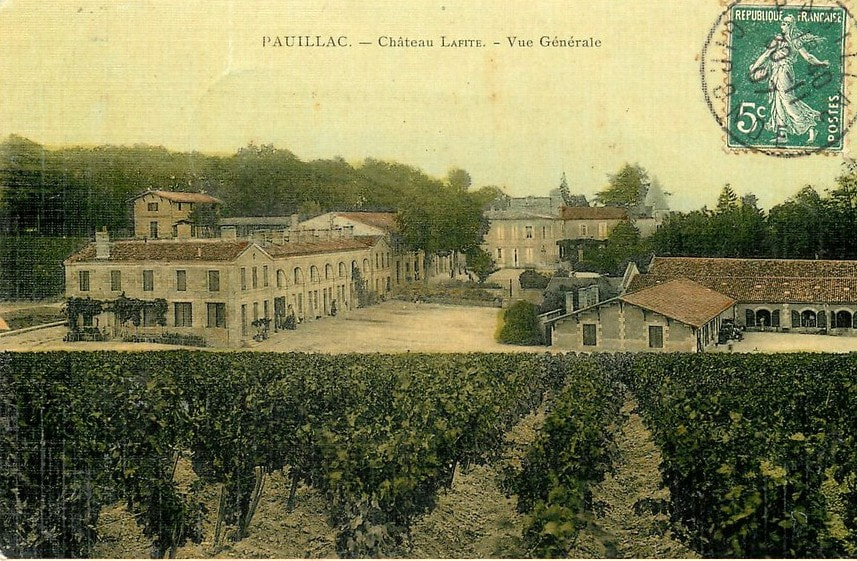

Executive director of trance hotels, graduate of École Hôtelière de Lausanne, and certified Court of Master Sommeliers, Suryaveer singh, takes us through the incredible history of wine.Benjamin Franklin once said “Wine is constant proof that God loves us and loves to see us happy”. The world of wine has a dark and mysterious past filled with ups and downs which run parallel to our very own existence as humans. In the mid-1970s a group of Archaeologists, working in the ancient site of ‘Khramis- didi- Gora’ in present day Georgia, stumbled across an artifact which would augment our understanding of the drink we know as wine. The artifact was an 8,000 year old Neolithic jar with fine engravings of grapes on it, used as a vessel in which to crush wine grapes and brew the delicate liquid which represented the terroir and love of the land. Such is the history of wine that it is intertwined with humanity’s history- wherever a civilization was set to thrive and flourish, the evidence of wine being grown is present. From the very moment the Ancient Chinese in 6000 BC discovered the art of fermenting crops into alcohol, humanity has twisted and turned alcohol recipes to suit palates for different ethnicities - be it beer or fortified rice wine. However, the terrain of modern-day Europe turned out to be ideal to grow wine through grapes and thus started the friendship of the Homo Sapien with wine. ‘Khramis- didi- Gora’ wine jug Wine seemed to serve numerous purposes for man - it was a safer to consume beverage over water, it was relatively easy to grow and consume, it was a valuable barter item, it was an ideal beverage to enjoy with food, the drink could be stored for longer periods and all sections of societies enjoyed it. The appreciation of wine in society is made visible with engravings of how to make it in the Pyramids of Giza in 2580 BC: King Tut’s tomb had countless wine jars for him to take to the after-life. On 197 occasions, the Old Testament mentions wine and refers to the beverage as ‘the blood of Christ’. Caesar used to command his mighty Roman army to consume up to 3 litres of wine a day/per soldier. Even Leonardo da Vinci didn’t shy from placing Jesus’ hand reaching for a glass in his iconic ‘The Last Supper’. Wine plays an integral part in mapping the history of Europe. Wine was introduced to the Mediterranean – present day Italy – by the Phoenicians in about 1550 BC, and the Roman Empire brought the crop from there to France. Throughout this time, the local population, through trial and error, figured out the most perfect and fertile plots of land to grow and perfect wine. One can examine the history of the renowned vineyards of Bordeaux in North Western France, which were historically under swamp water but drained by Dutch engineers in the 1600s’, as an example. The Dutch eventually farmed this land and turned it into a gravel and clay based soil – an ideal combination to grow award-winning wines. This new soil happened to bear fruit for the best wine making regions of Haut Medoc, and for wineries like Chateau Margaux and Chateau Lafite, which went on to be recognized by Napoleon and eventually the world as some of the greatest wines of our times. Chateau Lafite Winery The Romans perfected wine maturing in barrels along with the usage of hardened glass to protect the delicate liquid and showcase its most pure character. With wine thriving in Europe thanks to the Renaissance, the beverage was soon exported across the continent and throughout nations further afield through colonization. The discovery of the Americas, South Africa and Australia in the 1600s saw settlers bringing their favorite vines to new shores – George Washington being an avid wine grower himself. The New World, as it was referred to, had less rain and strong summers, which helped to ripen the fruit and bring about a more fruity flavored taste compared to the more mineral flavors in the European mainland. The 17th century was a seminal year for grape wine, with a sparkling variety of the beverage being introduced through sheer chance by a Christian monk named Dom Perignon in the Northern French town of Champagne. The world-of-wine now had a beverage to mark celebratory occasions. In 1703, tensions between the French and the British led to the development of Portugal growing wine of their own to feed the demand of Anglophiles. Portugal and Spain’s wine culture was disrupted under the rule of Islamic conquerors from 792AD to 1492AD. Greek youth using an 'oinochoe' or wine jug. 490-480BC The history of wine, however, does have a dark side. The beverage almost met its demise in the period from 1860 to 1890 due to an insect named Phylloxera which would chew the vines and ruin the fruit. Wine production from all countries dropped to a quarter in this period and with the growing popularity of alcoholic spirits, the wine market neared collapse. The industry finally figured out how to evolve their vines to withstand the bug and started to focus on the more common grape varieties of today- Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. The 20th century gave the industry a new challenge: with growth of the global population from 1.6 Billion in 1900 to 6.1 Billion in 1999, wine growers had to increase supply and adopt technology to rid themselves of archaic methods in order to improve their yield and quality. Two world wars caused a drop in production: the vineyards of Champagne were scenes of battle trenches, and cellars were looted. The state of Alsace in France, bordering Germany, exchanged occupation between the two warring countries, which resulted in the region producing German Rieslings with French finesse still to this day. The United States’ wine industry faced a devastating blow in the 1920s thanks to prohibition, which saw century-old vines uprooted and discarded. The industry lay dormant and discouraged until the 1960s. In 1966 an American called Robert Mondavi invested large sums of money to kick-start his very own winery in Napa, California. Mondavi’s winery encouraged others to follow suit and thus the golden age of New World wines began, with Californian wines often defeating their French superiors in blind tasting competitions. The New World, which comprised of non-European nations, adopted new techniques and methods such as temperature-controlled vats to ensure wine quality and screw caps to appeal to a new market. Today the New World produces more wine than any other single country. In 2019, the $423 Billion a year industry is at an exciting stage with strong demand from cash-rich China, overtaking the markets of Britain and France. With technology, wine growers are aiming to grow the grape in regions where, previously, none would have been deemed possible thanks to their long summers – India, China and Indonesia. Whatever we may see in the future, with global warming and the advent of artificial intelligence – wine will continue to remain man’s true companion, to sit beside him as one enjoys the fruits of life.  Suryaveer Singh, Executive Director of Trance Hotels Instagram: curious_sommelier ...that you were pronouncing the word caesar 'incorrectly'.We, at Versus History, must have taught Roman history - in one form or another - for a significant part of our careers. In the main, Roman history is delivered to the younger among our students and, if they remember little else (hopefully they remember substantially more than that), they remember the title and name ‘Caesar’. Now, I must have said the word ‘Caesar’ thousands of times over the span of my talking life but, I am rather embarrassed to say, it is only in recent years (perhaps the last seven) that I have pronounced it ‘correctly’.

Although the meaning of Gaius Julius’ cognomen (nickname, if you like) - Caesar - is debated (it either meant that he was ‘hairy’, born of a Caesarean section - ‘cut’, had ‘grey’ eyes, or killed an ‘elephant’!), what is universally agreed upon is the way it was pronounced: with a hard ‘c’ sound. As in ‘k’. For hundreds of years - up until 1066, in fact - English-speaking peoples pronounced the word ‘K-eye-ser’. It was the influence of the French language on English (after the Norman Conquest) which softened the ‘c’ of Caesar to the pronunciation we generally use today. Nevertheless, the original hard ‘k’ sound of the Latinate word spread and mutated via the Danes and the Germans, to the point where the English language once again incorporated ‘Kaiser’ to mean German ruler. Having said all of this, language does become correct by usage, so maybe I shouldn’t feel too guilty about pronouncing the original ‘K-eye-ser’ as ‘Seezer’. Dr Elliott L. Watson @thelibrarian6 ...Hollywood probably has it right, friar tuck was most likely overweight.Have you ever noticed the tendency in Hollywood or television series to depict monks, such as Friar Tuck in Robin Hood, as rather heavy set? I hadn’t; or at least it hadn’t registered until recently. Even if I had noticed this tendency I perhaps would have written it off as a lazy stereotype to be utilised for cheap gags or, in my more cynical moments, a sly dig at the opulence of the Church in the middle ages. However, there may be a little more this depiction than you might expect. A lot of the information that a historian has regarding gluttony on the part of monks is such that one must take it with a pinch of salt. Sources such as the reports conducted by inspectors of the Monasteries on behalf of Thomas Cromwell are easy to write off. These discovered monks engaged in a whole litany of vices, with gluttony being one of the seven deadly sins. Clearly such claims cannot be taken at face value given the vested interest such visitations had in finding wrongdoing. Much the same can be said for some of the anti clerical writings of the Reformation. However, recent archaeological investigation seems to have lent at least some credence to such accusations. Excavations of the remains of monks at three London based abbeys, for example, show the incidence of obesity related joint conditions to be five times higher than in the secular population.1 Moreover, the domestic accounts of some monasteries also paint a picture of indulgence, with monks eating five eggs and 700g of meat a day at St Swithun’s Priory in Winchester!2 Such information can hardly be deemed conclusive and we should not imagine that every monk, prior and friar was corpulent. To thoughtlessly extrapolate such limited data would be to stand on shaky ground. However, it does seem that Hollywood has a little factual backing for its caricatures of Friar Tuck and other monks as people who would mind going back for seconds. 1. Gilchrist & Sloane, Requiem: The Medieval Monastic Cemetery in Britain, 2005 2. M. Whittock, Life in the Middle Ages, 2009 Conal Smith

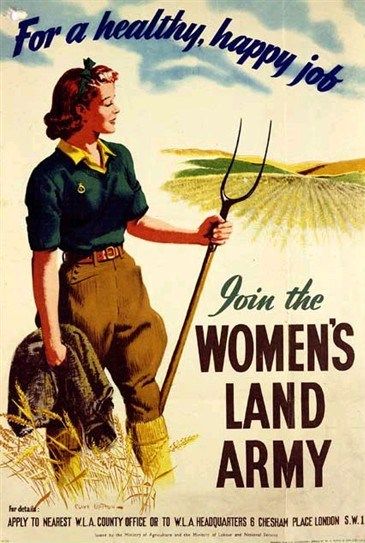

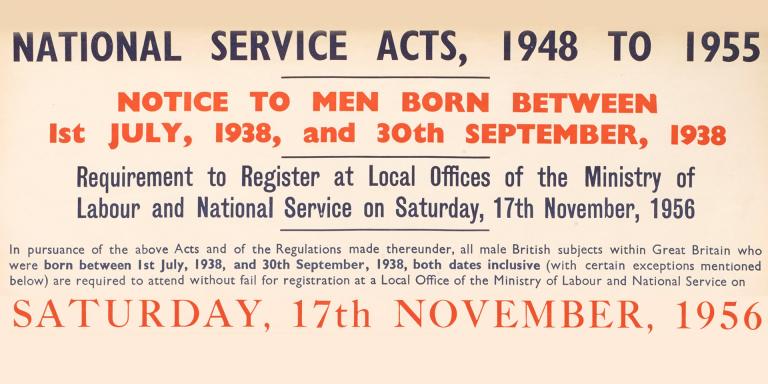

@prohistoricman ...AT LEAST ONE OF YOUR BRITISH ANCESTORS (PROBABLY) SERVED IN THE ARMED FORCES.Did your recent British ancestors serve in the Armed Forces? In short, at least one of them probably did, whether they be male or female, either as a professional soldier or as a conscript. The British Armed Forces have been a significant employer over the past 300 years. Men from across the British social spectrum have served the Crown and taken up arms (and those of many other countries, if Britain’s former colonies are included). Indeed, until the 1860s, men from wealthy and privileged social backgrounds could actually ‘buy’ a job as an Officer in the British Army! Those who were relatively less prosperous were still needed to serve both at home and across Britain’s sprawling Empire, although they were often drafted into the lower ranks of the British Army, or forcibly ‘press-ganged’ into service in the Royal Navy where the conditions were often harsh and the pay was low. In the twentieth century, however, via the process of conscription and national service, many British citizens who had not chosen a career in the armed forces were compelled to don a military uniform and serve under arms. During WW1, conscription was introduced in 1916, which meant that all unmarried men from 18 to 41 years of age were liable for service in the army. This was quickly amended to include married men and to raise the upper age limit to 51. In the era of attritional and highly mechanised warfare, Britain needed all the manpower it could get, even if the recruits had not willingly volunteered. Conscription was reintroduced for the duration of WW2, 1939-1945. This time women were conscripted, too. The British government was well aware that the contribution of every available adult would be needed if Britain were to successfully fend off the threat of Fascism. In 1941 it became legal to conscript single women between the age of 20-30 to undertake essential war work. By 1943, the majority of women - single or married - were undertaking work related to the war effort, even if they were not officially in the armed forces. In short, most men of service age would have served in the armed forces in some capacity during WW2 unless they were in one of the few exempt occupations and most eligible women would have served too. This means that if you have British ancestry dating back to this period, it is more than likely that they undertook service in some form during either or both world wars A further form of compulsion to serve in the armed forces was introduced in Britain from 1948 to 1960, in the form of National Service, where all men who were not registered as 'conscientious objectors' had to be available to serve. This was, in simple terms, peacetime conscription. If you have any male relatives who turned 18 during this period, it is possible that they may have participated in one of the conflicts that Britain was involved in at that time, such as the Korean War. Britain's global role changed significantly during the twentieth century. It went into WW1 as a superpower and emerged from WW2 as the junior partner to the USA in the Cold War. The process of decolonisation after WW2 and its commitments to NATO meant that Britain still needed a significant military presence.

The chances are that at least one of your British ancestors served in or supported the British Armed Forces in the Twentieth Century, in some capacity, whether they elected to (as many did!) or conscripted. Patrick O'Shaughnessy (@historychappy) ...president Harry s. truman didn't have a middle name. My name is Elliott L. Watson. My middle initial is L. and it stands for Lowther. The 33rd President of the United States, Harry S. Truman, had a middle initial and it was S. This middle initial stood for...S. Yes, S. By rights, there should be a second full stop (period) after those two S’s because not only do they come at the end of two separate sentences, they are also mandated by the U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual to come with their own full stop (period). Confused? Just wait. When Harry Truman was born he was to be given, like many of us, a middle name. His grandfather on his mother’s side was called Solomon Young; his grandfather on his father’s side was called Anderson Shipp Truman. Young Harry’s parents knew they would name him after one or the other but couldn’t decide immediately after his birth and, as a result, merely wrote his middle initial as ‘S’ on the register until a decision could be made. That decision was never forthcoming. Consequently, the future president went through life with a middle initial but no middle name. Harry Truman was adamant that his middle initial be followed by a full stop (period), despite it not being short for anything. Whenever he signed his name - from boyhood to manhood - he deliberately and clearly nailed a full stop (period) to the space directly after his middle initial. The only exceptions to this were when he signed his name using a single stroke of the pen. Because of Truman's emphatic punctuation, and for reasons of consistency, the U.S. Government Printing Office Style Manual decided that all governmental documenting of President Truman’s middle initial must carry the S followed by full stop (period). What’s in a name? In Harry S. Truman’s case, nothing. Apparently.

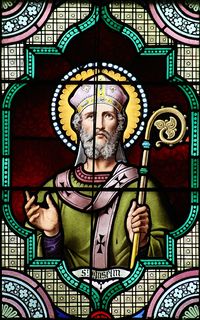

Dr. Elliott L. Watson @thelibrarian6 ...that slavery in england wasn't abolished by wilberforce et al.If one thinks of those who led to the abolition of slavery in Britain, inevitably one thinks of Wilberforce, Prince, Equiano and Sharpe. After all, that is what I and countless others were taught at school. Their role in bringing about the ending of the abhorrent trade in human beings in legislation of 1807 and 1833 is rightly remembered as crucial. However, a detail that is easy to miss in this story is that there was no slavery in Britain itself, it was limited to the British Empire.

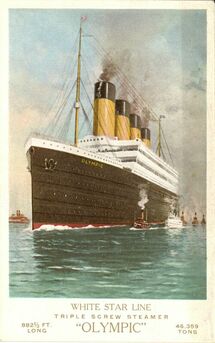

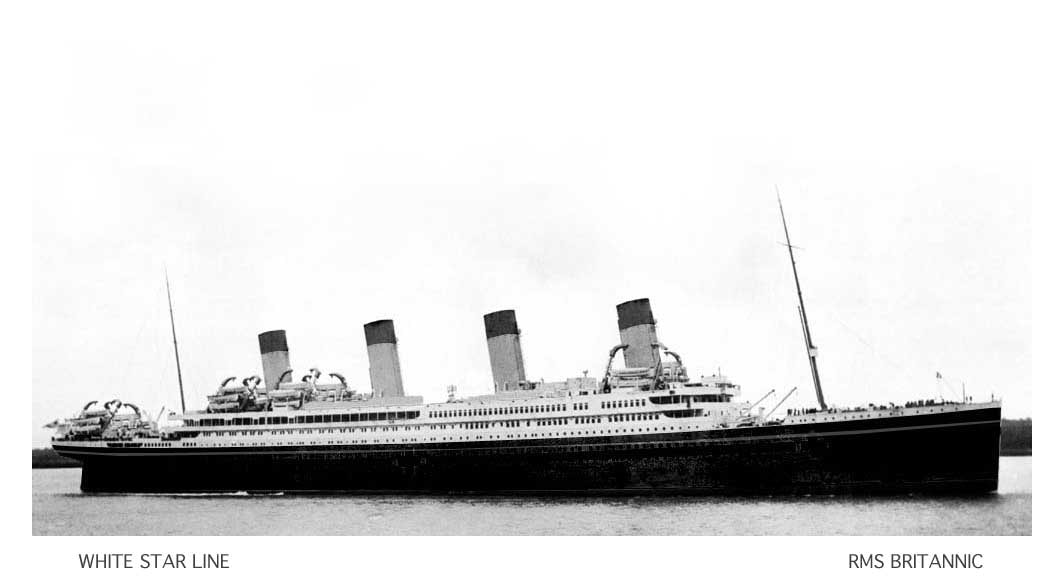

Slavery in England had been abolished way back in 1102 by the Statute of Westminster, overseen by the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Anselm. The capture and forced labour of men and women as slaves was a common feature throughout Europe in the eleventh century. Under the Vikings and Anglo-Saxons this was a trade in which England played an active part. However, in the 1102 Statute of Winchester a law was passed which included the provision “let no one hereafter presume to engage in that nefarious trade in which hitherto in England men were usually sold like brute animals” As is always the case in History, things are not as black as white as one might wish. After 1102 many people with in England remained unfree. They were forced to carry out unpaid labour services on their lord’s land, and were unable to leave without his permission, for which they were given the name of ‘villeins’. However, they could no longer be uprooted, shipped to far flung corners of the continent and sold to the highest bidder, as many of their fellow human beings would be over the next 700 years. For that there was reason for an Englishman to be grateful in 1102. Co-Editor, Conal Smith @prohistoricman ...THAT YOUR ENGLISH MEDIEVAL ANCESTORS WOULD MOST LIKELY HAVE BEEN TRAINED IN THE USE OF THE LONGBOW. bY LAW. The ‘bow and arrow’ has etched itself into English folklore. The legend of ‘Robin Hood’ and his trials and tribulations in Nottinghamshire’s ‘Sherwood Forest’ is a testament to that! Indeed, the English Army won some key battles in medieval history - such as Falkirk in 1298 and Agincourt in 1415 - due largely to their proficiency, skill and experience with the longbow. However, did you know that if you have English ancestry dating back to this period, then it is highly likely that you have ancestors who used the longbow, even if they didn’t fight in any battles during this period? This is because English men during Medieval times were compelled to use the longbow - by law. In 1285, archery targets were set up in every English town by King Edward I as part of the 1285 ‘Statute of Winchester’. To take this a step further, King Edward III mandated in 1363 that archery practice was mandatory on every feast day, Sunday and holiday for adult men. Therefore, by law, every English man able to do so had to take part: … every man ... if he be able-bodied, shall, upon holidays, make use, in his games, of bows and arrows... and so learn and practise archery. The reason for this is clear. The longbow had largely transformed the nature of warfare by this point in time. English Kings wanted (and needed!) to be able to call upon a reservoir of talented longbowmen from across the realm during times of War, which were pretty frequent during the Hundred Years' War, 1337 to 1453. Therefore, even if your English ancestors were fortunate enough to escape the horrors of the medieval battlefield, it is highly unlikely that they managed to elude the use of the longbow. ...that the Titanic was one of three near-identical ships built by the White Star Line. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed