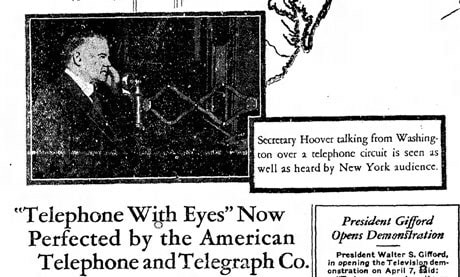

...THAT THE FIRST LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION BROADCAST IN AMERICAN HISTORY STARRED A SOON-TO-BE-PRESIDENT (It’s not who you think).At 3.25pm on April 7th, 1927, a group of journalists, Bell Laboratory executives, and AT&T President, Walter S. Gifford, listened to a voice transmitting from 200 miles away in Washington D.C.. Gathered in an auditorium in Manhattan, the attention of the audience was rapt, not by the voice - which was falling out of the loudspeaker - but to the grainy image that was moving in time with the voice. Walter S. Gifford, the President of AT&T, sitting in a leather-studded wooden chair that was raised about two feet from the ground, crouched over a standup rotary telephone that was itself perched on a shelf attached to a wardrobe-sized wooden box, and squinted into a small rectangle projecting at 45° from the same ‘wardrobe’. On the small rectangle, a picture of the man whose voice was spreading out from the loudspeaker, appeared. It also moved. At 18 frames a second, the monochrome picture, synchronised with the voice, created a staccato but recogniseable and moving form - that of Secretary of Commerce and future President of the United States - Herbert Hoover. Herbert Hoover appearing on America's first long distance television broadcast Referring to the demonstration, Hoover claimed, “Human genius has now destroyed the impediment of distance in a new respect, and in a manner hitherto unknown.” Despite Hoover’s enthusiasm, the front page of the New York Times proclaimed, the day after the display, that television’s “Commercial Use in Doubt”. If you are interested in watching a short video of the actual demonstration, follow this link: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=116047015077905 Dr. Elliott L. Watson @thelibrarian6

0 Comments

...ronald mcdonald has been a mcdonald's mainstay since the 1960s?McDonald’s probably has one of the most instantly recognisable brands in the world. Since its inception in San Bernardino, California in the 1940s, the fast-food restaurant chain has gained a truly global footprint, with well over 35,000 branches in over 100 different countries. That is pretty impressive. The Happy Meal, the Big Mac and the McFlurry are just some of the McDonald’s product range. When it comes to advertising the ‘McDonald’s’ brand, the ‘Ronald McDonald’ clown character has been a core feature of its promotional efforts, dating back to the same year that the USSR put the first woman - Valentina Tereshkova - into space. That was 1963! Since Ronald’s debut, the mythical character has had an interesting history. Here are just a few of Ronald’s 'history highlights' ... 1) Ronald McDonald’s early appearances in TV adverts indicated that he was a resident of an imaginary cartoon world known as ‘McDonaldland’, which he shared with the Hamburglar, amongst others. ‘McDonaldland’ landscape cartoons were a regular feature on the walls of McDonald’s restaurants in the 1980s, but these were gradually phased out and often replaced with more sober and corporate style imagery. 2) Ronald McDonald is not the only cartoon mascot for a fast-food burger restaurant chain. Wimpy - who were in direct competition with McDonald’s in North America and Europe in the 1970s and early 1980s - had their very own ‘Mr Wimpy’. 3) Ronald McDonald was a regular visitor to children’s parties across the world in the 1980s and 1990s. Anyone who hosted or visited an event at a McDonald’s restaurant around this time might have been lucky enough to receive a visit from the clown character himself. The author of this article has many such happy memories of Ronald. While Ronald McDonald remained a pivotal plank of the promotional activities of McDonald’s franchises in the Far East between the late 1990s-2010s, he was far less visible in Western Europe during this time. Indeed, in this geographical area, the chain largely mothballed the character. Ronald did, however, make occasional appearances in Happy Meal toys and promotions from time-to-time. Officially, Ronald McDonald was never retired and he remains a facet of the McDonald’s corporate image to this very day, albeit a less visible one in some areas.

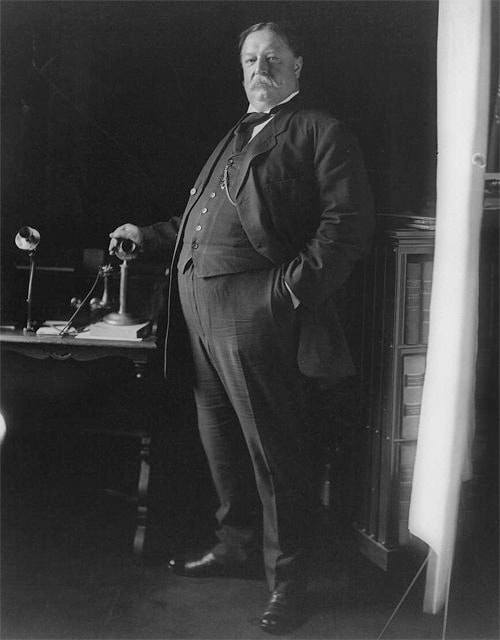

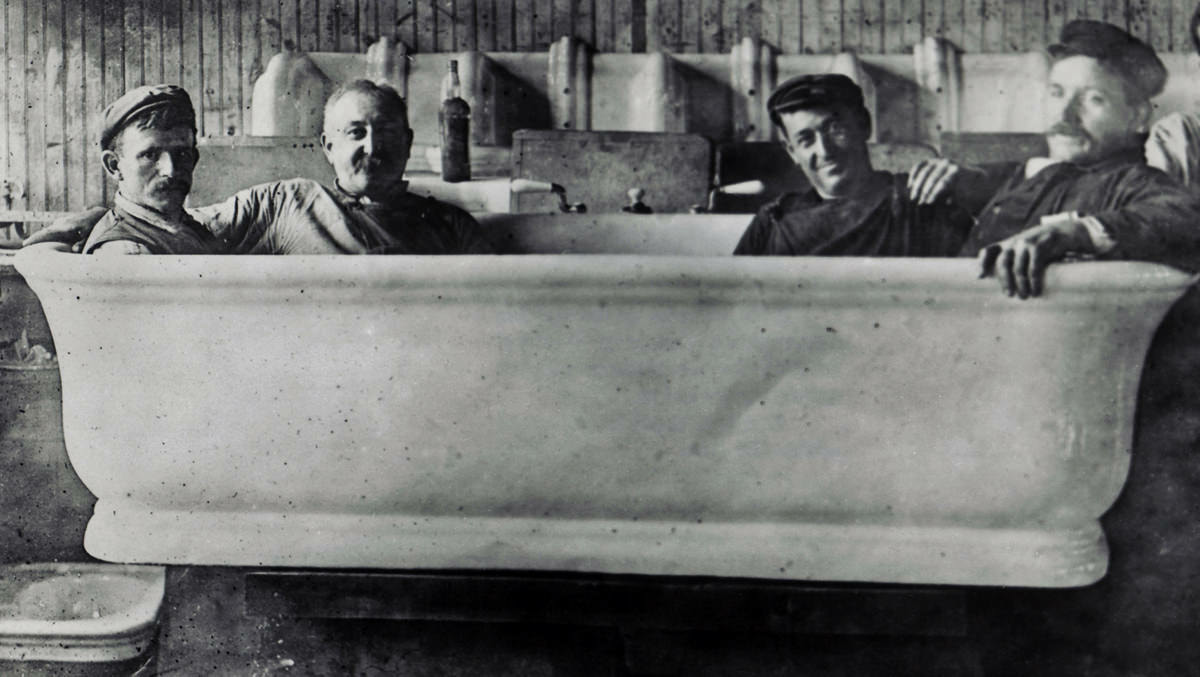

Patrick O'Shaughnessy (@historychappy) ...THAT DONALD TRUMP IS ALMOST, BUT NOT QUITE, THE ‘HEAVIEST’ PRESIDENT IN AMERICAN HISTORY.Last week, President Donald J. Trump had his annual health check up with physician Dr. Sean Conley. Despite being labeled by Dr. Conley as “...in very good health”, the President had increased his weight by 4 pounds (not quite 2 kilograms) since his last checkup. At 243 pounds, and 6 feet 3 inches, Donald Trump’s BMI index is 30.4. This pushes him into the category of ‘obese’. Since this is a history blog and not a nutritionist website, the healthiness or otherwise of this information will be left to experts. Having said this, historically-speaking, Trump is a heavy US president. He is, however, not the heaviest. That dubious honor goes to William Howard Taft. President William Howard Taft The 5 ft 11 inch 27th president of the United States was well over 350 pounds (nearly 160 kilograms) and had, according to a Forbes article entitled, A History of Fat Presidents, and written by Erik Kain, a BMI of 42.3. Despite the - most likely apocryphal - story of him getting stuck in the bathtub, President Taft was the first President of the United States to be advised by his physicians to go on a diet. With more than a minor penchant for steak, often breakfasting on the delicacy, it should come as no surprise that, even during an era when there was little societal pressure to diet, Taft was thought to be in need of a more ‘restrictive’ daily menu. Incidentally, Taft did die in his bathtub - but one that he had specially installed to accommodate his size. After his death, the media, who had ceaselessly mocked him for the size of his bathtub, became less...mean. President William Howard Taft's bathtub. President Taft’s physician, Dr. Nathaniel E. Yorke Davies, hailed from Lanrwst, north Wales, and was the son of the Headmaster at Lanrwst Grammar School. By all accounts, Yorke Davies was something of a nutritionist guru of the age - publishing a number of best-selling books on diet and exercise that captured the imagination of the time. His most popular book was Foods for the Fat: A Treatise on Corpulency. According to a New York Times article, entitled In Struggle With Weight, Taft Used a Modern Diet, the diet as advised by Dr. Yorke Davies, seems to have been such that modern Americans would find much in it that is familiar. The term ‘obese’ is very much a word belonging to the latter half of the 20th century - it replaced the equally unsettling, ‘corpulence’. According to the previously cited Forbes article, A History of Fat Presidents, the list of ‘Great Presidents’ as adjudged by Arthur Schlesinger Jr, seems to suggest that the corpulence of presidents is actually something of a boon to their historical ‘greatness’. Prior to the election of Donald J. Trump, the most ‘obese’ presidents were (in descending order) Taft, Grover Cleveland, William McKinley, Zachary Taylor, then Theodore Roosevelt. According to the BMI, President Trump would bump McKinley into fourth place. Taft enjoyed a ride. Dr. Elliott L. Watson

@thelibrarian6 ...That pigeons helped win wwii.While back in the UK over the most recent holidays my family and I were in the vicinity of Bletchley Park and so, as an indulgence to me, we decided to pay a visit. On visiting I was expecting to learn some nuggets about the mechanics of ciphers, codebreaking or the mechanics of the early calculating machine, the bombe. However, that my takeaway memory was provided courtesy of the Royal Pigeon Racing Association was something of a surprise. Attaching small messages to a bird in the form of a scroll and then allowing the bird to fly home has been a method of sending messages for a long time. Records of this date back to the Romans and possibly the Persians, but this practice has disappeared more recently than you might think. Pigeon post was very widespread in WWI and the stories of some of the more famous birds like the wooden-legged Cher Ami, are relatively well known. As a History teacher I have included them in lessons on WWI. Students are very often to hear of the scale of animals’ involvement in WWI with horses being the ‘backbone’ of transportation through much of the war; indeed the war saw the death of some 8 million horses! After WWI however, surely the widespread adoption of radio, telephone lines and technology made such ‘old-school’ methods as homing pigeons redundant? Not so, as I discovered to my surprise. During WWII, a conflict which saw such incredibly advanced technology as the atomic bomb, pilotless V2 rockets and radar, pigeons still played a mainstream role. Something of the order of 250,000 birds were used by the UK alone. Each and every RAF bomber took one with them on missions! Nor was this a solely British phenomenon, with virtually every nation and theatre of war seeing their widespread use. One could argue that this shows we should not discount analogue solutions so readily and, as I did, assume technology renders them otiose. However, it also serves to remind me that you never know what you will find as you get out and explore the History on your doorstep. To discover more about the role of pigeons in war visit https://www.rpra.org/pigeon-history/ Conal Smith

@prohistoricman ...your ancestors could choose death by crushing instead of entering a plea in court! but why would they?If your English ancestors stood trial for a crime in a court of law prior to 1772, the potential punishments - if convicted - could be extremely severe. For instance, when the Gunpowder Plotters were convicted of ‘high treason’ against King James I, they were hung, drawn and quartered. The potential punishments for those convicted of a crime during the Tudor and Stuart era could include - but were not limited to - being beheaded, death by hanging and being put in the stocks, depending on the severity of the crime committed. If prosecuted in a court of law for a capital offence (e.g: murder or treason) during the reign of King George III or a monarch preceding him, your English ancestors would have been faced with a simple choice. To plead ‘guilty’ or ‘innocent’ of the stated crime. Right? Actually, it’s wrong! The choice of plea facing the accused at the start of the trial was not actually a simple binary between ‘innocent’ on the one hand and ‘guilty’ on the other. There was a THIRD option! This is where things get slightly complex. We can safely assume that a plea of ‘guilty’ in a trial for a capital offence would have meant almost certain conviction, death and the subsequent forfeiture of all land and property owed to the Crown. A plea of ‘innocent’ would have either resulted in the previous outcome or, if one was lucky, an acquittal (although this was unlikely in treason cases as these were often a fait accompli). The third option would have appealed to those with significant estates and wealth. To avoid the seizure of all property and estates by the Crown, the accused could refuse to enter a plea. This could result in what was known as peine forte et dure. In English, this meant ‘hard and forceful punishment’. This involved the defendant being subjected to crushing by increasingly heavier rocks; the idea being to elicit a plea from the defendant, which would then result in the trial being resumed. However, if the accused perished during the ‘crushing’ process, they would technically die as an ‘innocent’ person. Therefore, the ‘next of kin’ could inherit the wealth of the deceased, rather than it being seized for the Crown. So, until 1772, the wealthier the defendant in a capital offence, the more incentive they had to refuse to enter a plea. The past was indeed a strange place. Patrick O'Shaughnessy (@historychappy) ...THAT NAGASAKI WAS NOT THE ORIGINAL TARGET OF THE SECOND ATOM BOMB IN JAPAN.Mushroom cloud over Nagasaki. (US gov [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) At 8.15am on August 6th 1945, a B-29 Superfortress from the 393rd Bombardment Squadron called the Enola Gay - named after the mother of its pilot, Paul Tibbets - released a bomb carrying 64kg of uranium 235. After just under 45 seconds of freefall, Little Boy - this was the name of the atom bomb - detonated at 580 metres above the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Close to 80,000 civilians died instantly. When the Japanese Imperial Army refused to capitulate, a meeting on the US-controlled Pacific island of Guam, including such military luminaries as General Curtis Lemay and Rear-Admiral William R. Purnell, was convened to determine the next move. With no Japanese surrender forthcoming, the ‘next move’ was adjudged to be the dropping of a plutonium-based weapon, codenamed Fat Man (named by Robert Serber of the Manhattan Project after a character in The Maltese Falcon) over the city of Kokura. Kokura, in the south west of Japan was, incidentally, the secondary target had Hiroshima been cloud-covered on the 6th of August. Now it was the primary target. 'Fat Man' being sprayed with plastic on the island of Tinian At just after 3.45am on the 9th of August, another B-29 Superfortress - this time named Bockscar - took off from the island of Tinian in the Pacific Ocean, loaded with Fat Man, and headed towards the Kokuran military arsenal. After rendezvousing with support planes above Yakushima Island, Bockscar flew onto Kokura. For a good portion of the final months of the war in the Pacific, the USAF had been firebombing the mostly wooden cities of Japan in the hopes of causing such terrible civilian casualties and damage to property that the High Command would be forced into surrender. During the previous day, American bombs had set fire to the nearby city of Yahata. The smoke that continued to billow from the city obscured the primary target of Kakura such that, despite three bombing runs above the target, the Bockscar could find no opening in the cloud cover. As a result, the secondary target was selected. Nagasaki, and not Kokura, would bear the brunt of history’s atomic age. B-29 Superfortress, Bockscar. (ASAF [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) Two minutes before any clock in Nagasaki struck 11am, Fat Man fell from Bockscar. 43 seconds later, one gram of matter (from the 6.19kg of plutonium) was converted into heat and radiation 500 metres above the ground. Approximately 40,000 Japanese people died almost immediately. The number of deaths would have been far higher had it not been for the mountainous topography of Nagasaki which helped shield some residents from the blast. As it was, tens of thousands died from leukaemia and other radiation-related illnesses, as well as the fires that raged long after. Atomic cloud over Nagasaki from Koyagi-jima(Hiromichi Matsuda (松田 弘道, ?-1969) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) Dr Elliott L. Watson

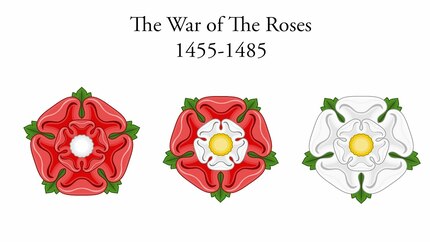

@thelibrarian6 ...THE BATTLE OF BOSWORTH DIDN’T END THE WARS OF THE ROSES. THEY NEVER EVEN HAPPENED.Every Briton who has studied the Tudors would be able to tell you that the first Tudor King, Henry VII, became King because he killed Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth. Thus far they would be correct, but if they were to say this ended the Wars of the Roses they would be wrong on a number of counts. Firstly, and perhaps most simply, the Battle of Bosworth was not the last battle in the struggle between York and Lancaster. Even after Henry had married Elizabeth of York in 1486, thereby supposedly uniting the two Houses, he had to fight to hold his throne. In 1487, with Henry having been on the throne for two years, a sizable Yorkist army of 8,000 was mustered, sailed from Ireland to Lancaster and thence marched into the Midlands. This army was gathered in support of the claim of Lambert Simnel (or Edward of Warwick if we believe the “pretender’s” claims). Simnel’s forces were comprehensively beaten at the Battle of Stoke, but clearly Bosworth was not the conclusive end to the conflict between the two Houses which is in our popular imagination. Moreover, even the Battle of Stoke cannot be considered the end of the struggle. This is not just because there were further pretenders to the throne, such as Perkin Warbeck, championing the Yorkist cause, but rather because the Wars of the Roses never happened. In Henry VI Part 1, he has nobles pluck a flower as a badge of their allegiance: PLANTAGENET Let him that is a true-born gentleman And stands upon the honour of his birth, If he suppose that I have pleaded truth, From off this brier pluck a white rose with me. SOMERSET Let him that is no coward nor no flatterer, But dare maintain the party of the truth, Pluck a red rose from off this thorn with me. WARWICK I love no colours, and without all colour Of base insinuating flattery I pluck this white rose with Plantagenet. SUFFOLK I pluck this red rose with young Somerset And say withal I think he held the right. However, the white and red roses were not universal symbols of Lancaster and York in the mid fifteenth century. Instead, the white rose was only one of many symbols associated with York; with the yellow sun being more common and Richard I fighting under a white boar. For Lancaster there is even less evidence of the red rose being a defining symbol. Instead, the Lancastrians tended to fight under royal coats of arms, with only the household servants using the red rose for demarcation. Henry VII seemingly adopted the red rose out of symbolic convenience when he married Elizabeth of York. Thus allowing him to create a visual symbol of the union of the Houses in the Tudor Rose. By using the term the Wars of the Roses, we then are unwittingly utilising and propagating Henry VII’s propaganda. He would be very happy to hear us use it, even if those who lived through the Wars themselves would be rather perplexed.

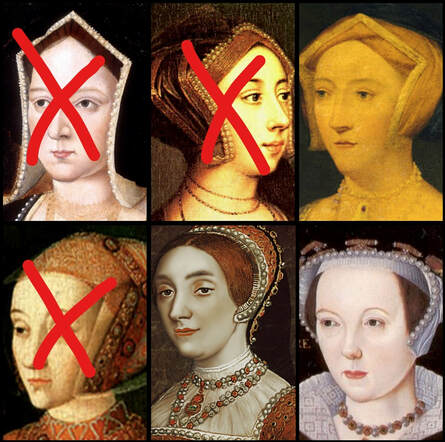

…THAT KING HENRY VIII DID NOT HAVE SIX WIVES. Ok, hopefully that got your attention. It is mostly the case that the study of History requires a degree of contextual empathy that is often lacking in the manner by which the subject is taught - particularly when that subject is a supposedly ‘well known’ one. As in the case of King Henry VIII. Too often we are guilty of examining the subject from our ‘future’ vantage point and looking backwards in time, examining it, if you will, at a ‘contextual distance’ and not from the contingent perspective of the time occupied by the subject. It is often easier to merely repeat the basic historical tropes - Henry VIII had six wives - than it is to evaluate their authenticity. Putting it in a simpler form, if you were king Henry VIII, in the 16th Century, how would you have replied to the following question, presuming that it had been put to you at the end of your reign: “How many wives did you have, sire?”. The authentic reply would most likely have been, “I have had three wives”. Without exploring the semantics embedded within the language of marriage too deeply, the key difference (as I see it) between the History we can often be taught in school versus the contemporary experiences as they were lived at the time, is distilled perfectly, microcosmically-speaking, in the difference between two words: annulment and divorce. Only one of these are we routinely taught when exploring Henry and his ‘wives’: divorce. A divorce is the legal dissolution of a valid marriage - an acknowledgement that there used to be a marriage, and always will have been one in the eyes of the law and therefore of history; an annulment, is a legal recognition that a marriage was never valid in the first place and thus never actually existed - both legally and historically. Of course, the language of annulment is very clearly designed to create a legal and historical ‘resetting of the clock back to zero’, so that whatever follows, maritally-speaking, will always take precedence over what has gone before. Which, technically, is nothing. Cardinal Wolsey laboured unsuccessfully to get Henry an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon. Thomas Cromwell was able to get the annulment, but ultimately fell foul of Henry's executioner. Both Thomas Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell expended great energies navigating the legal language of their king’s ‘marriages’. And with particular reason. The semantic and legal tenor of the word 'annulment' was incredibly helpful for King Henry because he needed to void any claim of Mary (the child he shared with Catherine of Aragon) and Elizabeth (the child he shared with Anne Boleyn) to the Tudor throne. He needed a male heir - which was provided to him by Jane Seymour the moment she gave birth to Edward. And so, if Henry had been asked in the year of his death how many wives he had had, he almost certainly would have replied (particularly having irreparably altered the legal and religious landscape of England by his marital maneuverings) that his first wife was Jane Seymour, his second was Catherine Howard, and the third and final was Catherine Parr. He would, no doubt, claim that he had never actually been married to either Catherine of Aragon, Anne Boleyn or Anne of Cleves. Legally, and thus historically, speaking, he never was. By saying that Henry had six wives instead of three, while simultaneously using the historically redundant noun ‘divorce’ in our teaching of the subject, we may be guilty of historical laziness at best, or historical disingenuity at worst. Dr. Elliott L. Watson @thelibrarian6 ...SIX OF THE ORIGINAL THIRTEEN COLONIES ARE NAMED AFTER BRITISH KINGS & QUEENS!On 4 July 1776, the Thirteen Colonies of British North America withdrew their allegiance to King George III in the Declaration of Independence. The fighting that ensued between the British and the American Patriots was bitter, costly and was considered to be a ‘civil war’ by the British. Hence, no British Army regiment was ever awarded battle honours for their role in the conflict. The American Revolutionary War rumbled on until 25 November 1783, when the final remnants of the British Army were evacuated from Manhattan, New York. However, while the Declaration of Independence accuses the British King of establishing an “...absolute Tyranny over these States”, you may be surprised to learn that six of the original thirteen colonies of British North America took their names from British monarchs.

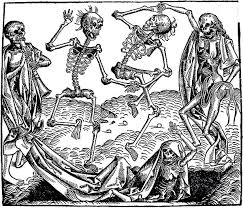

Therefore, in a sense, the connection between America and its former monarchy lives on (in name only), some 243 years after independence. Patrick O'Shaughnessy (@historychappy) ...the black death was actually a good thingIf you know anything about the Black Death, it is most likely that it was a horrible disease that killed huge numbers of people right across Europe a long time ago. This is certainly true, but did you know that (so long as you escaped the illness) it actually hugely improved life for most people in Britain? In the year 1348 a terrible condition began to strike people in England and rampaged through the nation for the next four years. A contemporary description by Giovanni Boccaccio gives us a graphic view of the horrors of the disease which “began both in men and women with certain swellings in the groin or under the armpit. They grew to the size of a small apple or an egg, more or less, and were vulgarly called tumours. In a short space of time these tumours spread from the two parts named all over the body. Soon after this the symptoms changed and black or purple spots appeared on the arms or thighs or any other part of the body, sometimes a few large ones, sometimes many little ones. These spots were a certain sign of death, just as the original tumour had been and still remained” To catch the disease was clearly extremely painful and unpleasant, but also fatal in most cases. Estimates of the casualty rate in England range from one third of the population to roughly half. On a national level it was a disaster. This was perhaps most obvious for those who caught the disease. However, with such a high mortality rate everybody would have close family and friends struck down and been affected in the most harrowing way. Yet, the survivors of the disease actually found their lives materially improved in the second half of the fourteenth century. With such a high proportion of the population removed, and therefore the available pool of labour shrunk radically, peasants, as the majority of the population were, found themselves in demand. Statistical data is inevitably patchy, but the laws passed by the government in the wake of the Black Death reveal the increased value in peasants’ labour.

The Ordinance of Labourers, a law of 1349, stated that when hiring workers “no man pay, or promise to pay, any servant any more wages, liveries, meed, or salary than was wont, as afore” (before the plague) As well as attempting to freeze wages the Ordinance also placed a price freeze on staple foodstuffs such as meat, fish and bread as well as the price that could be charged by skilled craftsmen such as smiths. Fortunately for the labourers of England, evidence suggests this law was unsuccessful. It was followed up by another legal attempt to restrain prices in 1351 called the Statute of Labourers, but neither of these seem to have had a large impact; as many economists will tell you, market forces can be hard to control. In his seminal work Making a Living in the Middle Ages, Chris Dyer states that “the rise in wages was at first modest, and striking improvement often came in the last quarter of the fourteenth century”. So there it is. If you were an agricultural labourer, as most Englishmen were, and you survived the Black Death, you could gain a little more coin for your hard labours and perhaps find it a little easier to put food on the table for yourself and your family. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed