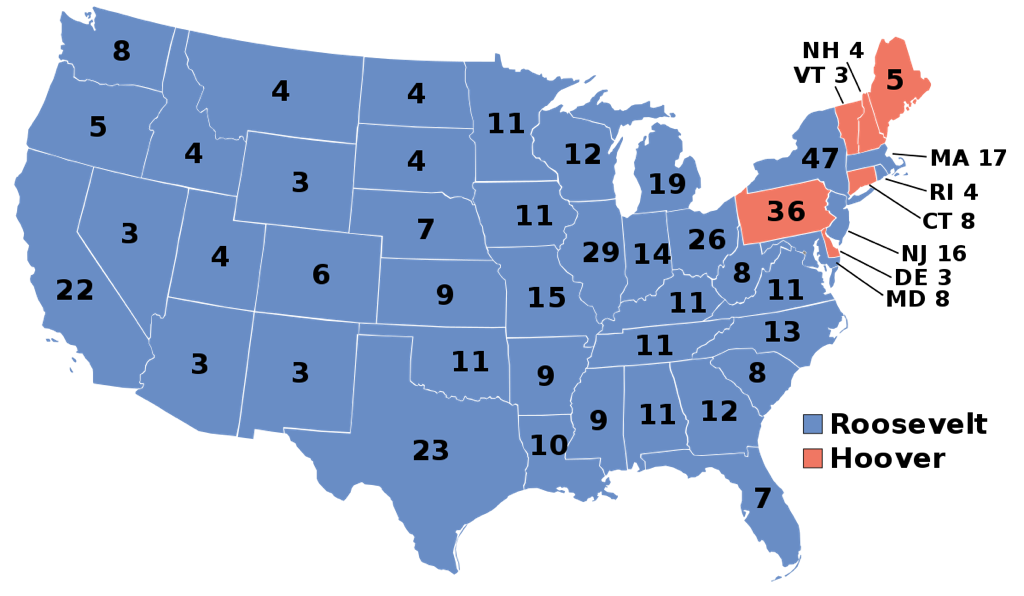

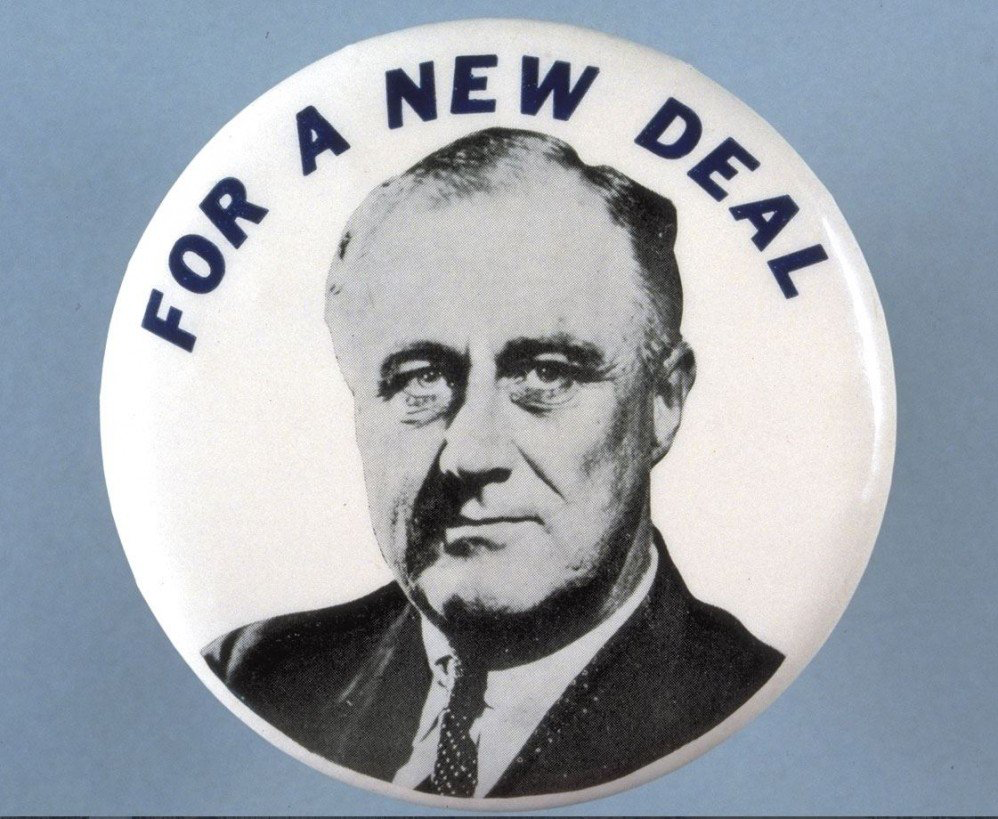

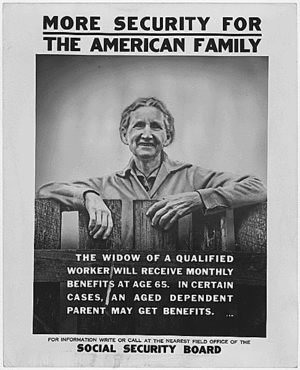

The New Deal: Three lessons on the malleability of significanceStudents of history are often charged with determining the significance of events, issues and people. The New Deal offers a wonderful opportunity to delve into the many ways that significance can be determined, assessed, and deployed. In March 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took control of the White House from Herbert Hoover. FDR was a man born into a wealthy New York family and was as close to an aristocrat as you were likely to come across in interwar America. He held public office almost unceasingly from 1910 (when he became the Senator for New York) until his death in 1945 whilst serving as President. Hoover was a self-made man, beginning his career as an engineer and developing himself into a very successful businessman. He entered public office as the head of the US Food Administration during the First World War, creating a name for himself as a global humanitarian. As Secretary for Commerce during the 1920’s, Hoover was known for his dedication, professionalism and efficiency. A Republican, he served as the 31st President of the United States from 1928 until his humiliating defeat to the Democrat, Roosevelt, in 1932. Rarely has there been a US presidential election that so starkly illustrated the differences between the modern incarnations of the Republican and Democratic Parties. For the majority of the 1920’s, the central tenets of Republicanism - ‘Rugged Individualism’, a laissez faire approach to economic growth, a fervent (near hysterical) aversion to socialism, and an unwavering belief in the robustness of the American Dream - dominated the economic, social, and political landscape. Three successive Republican presidents, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and then Herbert Hoover, presided over an America that appeared (at least on the surface) to be immune to the normal boom-bust cycles of economic theatre. In fact, in a campaign speech in 1928, Hoover stated that, “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land”. In less than a year, the US stock market crashed and the country entered a period of sustained economic collapse. Roosevelt, a man who, over a decade earlier, had expressed a desire to see Hoover become president, stood against many of the principles upon which Hoover and the Republican establishment - so long the saviours of America after the upheaval of the Great War - had based their policies. In his campaign, FDR had offered the American people a ‘New Deal’. What this ‘New Deal’ constituted was kept deliberately vague, but it promised something that Hoover and his fellow Republicans (who had naturally borne the brunt of public dissatisfaction over the problems associated with the Great Depression) seemed incapable of demonstrating: action. In his inaugural address on the 4th March 1932, FDR said the following: “This Nation asks for action, and action now”. Whatever the reality of the promises he made and the solutions that he proffered in the build up to the election, the American public bought into them. He beat Hoover in the presidential election of 1932 with 472 Electoral College votes to Hoover’s 59. FDR took around 60% of the popular vote. The following are three lessons that I have learned through my study of FDR and the New Deal. The following are three lessons that I have learned through my study of FDR and the New Deal. The Semantic Lesson: What’s in a name? FDR and his writers were familiar with, and understood the value of, the post-war print and radio media. Although he was prolific in his campaign movements around the country, personal appearances at rallies would always be restricted by his polio, the size of the US, and the challenges associated with criss-crossing it. The ‘New Deal’ was crafted as a slogan before it ever became a set of principles and policies and it was designed to encapsulate all that Roosevelt offered and all that differentiated him from Hoover and the Republicans. Economist, social theorist, semanticist and advisor to Roosevelt, Stuart Chase created the modern manifestation of ‘A New Deal’ (although in purely literary terms it belongs to Mark Twain) and essentially offered it to FDR as a piece of semantic perfection that would resonate with the electorate without denoting specific policy stipulations. Anything ‘New’ meant change and any change meant difference. Any difference meant the opposite of what had come before. The opposite of what had come before could only be better than what had happened, and was continuing to happen in America. In 1932, there were roughly 18 million Americans unemployed (nearly a quarter of those men and women employable). By the end of 1932, most banks were closed or had gone bankrupt. GDP had collapsed to less than half of what it had been before the Wall Street Crash. Whatever it meant in truth, to the electorate it was clear that ‘New’ was a good thing. The Republicans had spent over a decade reinforcing the truism that an administration’s approach to governance was only successful when that governance was ‘hands off’. Success in all walks of life was due to individual hard work and a steadfast belief in an unregulated private sector. Consequently, when the country went to Hell in a handbasket, the people of America lost faith in those principles of Republicanism which had, for so long, trumpeted self-help over community assistance, as well as government non-intervention. Hoover was labeled (quite incorrectly, in many respects) a ‘do nothing president’, at a time when the people of America were desperate for help. FDR’s New Deal offered that help. In fact, it offered them a ‘deal’ - a partnership. No longer would Americans feel ‘forgotten’ in their time of need. US citizens would no longer feel alone and abandoned because Roosevelt and his administration were ‘in it with them’. Their problems were his problems, and vice versa. Perhaps for the first time in US history, the government du jour would cease to be a remote and unsympathetic entity, it would be an equal partner with, and have an equal investment in, the success and wellbeing of its citizens. One (the government) would be indistinguishable from the other (the citizens). A Deal’s a Deal. Particularly a New one. The Political Lesson: The difference between success and failure depends upon your vantage point In the most recent New York Times rankings of ‘Presidential Greatness’ - a poll with a variety of metrics and revisited every four years - Franklin Delano Roosevelt ranks third behind Abraham Lincoln (1st) and George Washington (2nd). Among Democratic, Republican and Independent scholars, his position is unmoved and has remained that way for almost as long as the poll has been going. And yet, and yet... FDR did not end the problems associated with the Great Depression - he didn’t even come close. So, how is it that we can judge FDR as worthy of such historical praise, even though it is summarily accepted that the Great Depression evaporated almost as soon World War Two began, rather than because of the impact of the New Deal? The answer (in addition to everything else contained in this post) is simpler than you might imagine: there are always different interpretations of ‘success and failure’. A simple example might be: unemployment during the early days of the Great Depression reached 18 million; by 1939 it was 9 million. A critic would judge 9 million people as an extraordinary number of Americans still unemployed - and thus cite the New Deal as a failure in its ‘primary task’: that of putting people back to work. Others, including FDR himself, would take the same evidence and, using a different vantage point, would turn the same statistic on its head, arguing that the New Deal was able to cut unemployment by 50% in 6 years. Perhaps another example, should one desire to have another, might be that whereas many countries in Europe began turning to extremist politics for solutions to the economic damage wrought by the worldwide depression - the obvious being the fascist risings in Germany, Italy, and Spain and the tide of communist support pushing into mainstream politics - the United States was never troubled by any such dangers. Even in the UK - the supposed bastion of even-tempered, long suffering souls, Oswald Mosley gained tremendous support for his Hitlerian-style aspirations. Is it fair or right to say that the New Deal was responsible for maintaining America’s resolute adherence to democracy and capitalism? Maybe, maybe not. It depends upon your vantage point. The Historical Lesson: Precedent is often more important than achievement As we have just read, the Great Depression and its associated problems still continued, for the most part, unabated until the outbreak of World War Two. If the New Deal did not kill the Depression, then why discuss it at all in terms of achievement? Franklin Delano Roosevelt won an unprecedented four presidential elections and there is no reason to think that, had he survived, he would not have won a fifth. The 22nd Amendment to the US Constitution, ratified in 1951, put restrictions on those looking to hold the office of the presidency, stating that “No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice”. This was, without doubt, a response to the tenure of FDR. Though many precedents were set by the 32nd president that were to be followed by others, his four term presidency was not one of them. Precedent 1: Regulating stock brokers can often be like taking candy from a baby - they may cry, but it’s good for them to understand that overindulgence can lead to problems later. Prior to the New Deal, regulation of the Stock Market was seen as unnecessary, unwelcome, and dangerous. Consequently, activities that we would consider crimes today (and in truth were crimes that went unpunished then - so called ‘blue sky laws’ were ignored en masse) such as insider trading, manipulating markets, cartels and such, were overlooked and, in fact, often actively encouraged because of the government’s ideological commitment to deregulation. However, after the crash of 1929, many in government (even some Republicans) saw that the stock market required some form of federal control. The Securities Exchange Act of 1934, passed to enforce the Securities Act of 1933, created the Securities and Exchange Commission - more commonly known as the SEC - which was designed specifically to tackle the corruption and lack of transparency of the US Stock Market. The SEC did much to restore/instill public faith in the way the American stock market would operate and helped to stabilise, in relative terms, Wall Street. However, the achievement of the SEC, bearing in mind its first chief was Joe Kennedy - the wildly successful financial malepractor and prolific breaker of banking laws -, is its existential longevity as well as its value as a precedent that would be followed by governments across the world. The SEC continues to regulate Wall Street to this day and well over half of the world’s countries have their own version. Precedent 2: Government intervention isn’t always a bad thing Despite the emergence of the progressive parties and politicians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the American people still remained, until 1933, a people encouraged (if not downright forced) to fend for themselves. The principles of ‘Rugged Individualism’ had dominated North American life for centuries (the products of which were embedded as thoroughly in the political landscape as they were in the physical) but they had recently come to represent the inadequacies of three Republican administrations. As a result, Roosevelt decided early in his presidential campaign that his government needed to look out for the ‘forgotten man’ of America. Hoover once said that “If a man has not made a million by the age of 40, he is not worth much”; FDR, on the other hand, said that government plans must ‘...build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid”. Roosevelt’s New Deal may very well have failed to rescue the country from the deeper-set problems of the Great Depression, but one thing it did achieve was a general acknowledgement from many within the political establishment, and a keen expectation from many Americans, that government needed to do more to protect its citizens from hardship. It was no longer sufficient for government to create an environment conducive to prosperity, it also needed to provide a safety net for those who were either unable to take advantage of that environment or those who suffered when that environment evaporated. As it did in 1929. Perhaps the greatest example of the New Deal’s paradigm shift towards the social and economic wellbeing of its citizens can be found in the Social Security Act of 1935. This remarkable piece of legislation introduced federal funding for old age pensions, child welfare, public health, people with disabilities, and unemployment insurance. In this, as well as other New Deal laws, were distilled the essence of the New Deal, and this essence - although not always successful - projected into the future of America. Perhaps ‘Obamacare’ is one of the most recent examples predicated upon the precedent established by the New Deal. Precedent 3: Presidents must be seen to be doing something While there is no doubt that Roosevelt was indeed a man of action - his first one hundred days in office were busier in terms of federal and executive action than any that had gone before and possibly after (regardless of President Trump’s assertions) - there is also no doubt that Herbert Hoover worked himself to exhaustion trying to solve the problems of the Depression. However, while there were clear ideological differences between the two men, and these certainly contributed to the outcome of the 1932 election, one of the more immediately recognisable differences (to the detriment of Hoover) was the ‘media savvy’ that one demonstrated and the other catastrophically failed to understand. No matter how hard a president actually works, he must be seen to be working. Hoover never understood the value of appearance - this is why he was labeled the ‘do nothing president’; FDR embraced the media and was, perhaps, the first of the ‘modern’ presidents, inasmuch as he he understood the importance of appearance as well as reality. Different historians characterise FDR’s relationship with the media using different adjectives: Graham J. White saw in Roosevelt a ‘virtuosity’ in his handling of a press that could not “...cease to admire” him; Leo Rosten, however, believed FDR was more cynical, turning his media charm on and off like a ‘faucet’. None, however, doubt that his relationship with the media was significant in the life of the New Deal. From his 998 press conferences during which crowds of reporters swamped his desk and freely asked their questions - unprecedented in the access they were afforded to the president -, to the famous ‘fireside chats’, whereby the reassuring actions of his government and the optimistic expectations he had of the American people, would be laid out in 31 radio addresses across his four terms, FDR was unlike any other president before him. Even those Americans who were unimpressed by either his policies or the ideology that underpinned them, could not fail to admire the image that he had created for himself through the media - as an energetic and active workman. This cultivated image (warranted or otherwise) is made all the more impressive when we remember that he was confined to a wheelchair for the duration of his presidency. How many photographs have you seen in contemporary newspapers of FDR in his wheelchair? I’ll wager good money that the number is low. With the advent of television and then social media, the importance of presidential appearance has become almost as important as the work done by the president. There is a strong case to be made that Roosevelt created this Presidency of Appearance. Dr Elliott L. Watson

Co Editor of Versus History

0 Comments

British-Australia was established 84,766 days ago (at the time of writing - 23 February 2020). Today, the Commonwealth of Australia has a democratically elected prime minister and a hereditary monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. Her Majesty is represented in Australia by the Governor-General. Unlike today, however, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, power was concentrated in hands of the governor appointed by Britain, resident in Australia. The fifth governor, Lachlan Macquarie, featured in one of the recent GCE / A-Level History examinations. The question required that students analyse his contribution to the development of British-Australia in the early nineteenth century. So, then, what are the key three things that we should know about the man?  Portrait of Governor Lachlan Macquarie, 1810-1821. Portrait of Governor Lachlan Macquarie, 1810-1821. Lachlan Macquarie in Context New South Wales was established as a British penal colony in January 1788, during the reign of King George III, as the intended repository for the ever-growing number of convicted criminals in Great Britain at the time. Previously the Thirteen Colonies of British North America had been the destination of transported criminals. However, with the loss of America in 1783, Britain was in desperate need of an alternative. British jails were massively overcrowded in the late 18th century, to the extent that decommissioned ships were converted into temporary floating prisons. The alternative to America was some 16,500km from London, rather than the 5,500km to New York. Australia was - in the eyes of the British judicial system - ersatz America. Historian Lawrence James argues: "They (convicts) were to provide the sinews of a new colony that, in time, would profit Britain, which would be preferable to having them idling in prison cells or the hulks." The new ‘pop-up’ penitentiary was populated mostly by convicted felons in its early days. It was initially marshalled by the New South Wales Marine Corps and then quickly relieved by the New South Wales Corps between 1789-1810, whilst being run by a governor appointed from London. Indeed, whilst the American colonists had chafed under the rule of the various British governors before 1776, early British-Australian convicts had virtually no say whatsoever in the governance of the colony. This responsibility rested solely with the Governor, backed by a cadre of Redcoats for muscle. Convicts were in Australia to serve sentences, work and, if they were able to serve the duration of the time spent at ‘Her Majesty’s Pleasure’, gain a small land grant. Into this context entered Lachlan Macquarie. He became the fifth governor of New South Wales, serving between 1809-1821. Arriving some 21 years after the establishment of British-Australia, Macquarie was tasked with developing the colony and ensuring a swift and sustained return to good discipline and order. Indeed, it was not just the convicts that needed correction. The New South Wales Corps themselves had rebelled in 1808. Against this turbulent backdrop, Macquarie commenced his role as the Governor, some six months after setting sail from Britain. What three things should we know? 1) Macquarie built. He took the reins of British-Australia in 1810; this was a turbulent and testing period in the nation’s history. By the time that Macquarie had relinquished his post in 1821, the colony was significantly more stable and prosperous than when he had arrived. The elaborate building works in Sydney were a testament to his grandiose vision for the colony. Moreover, the footprint of Macquarie can still be seen in Australia’s earliest towns. He assiduously nurtured the development of the five ‘Macquarie Towns’ - Castlereagh, Pitt Town, Richmond, Wilberforce and Windsor - which laid the platform for early and future urban development in Australia. These towns were built towards the ‘Blue Mountains’, where sheep farming - one of the primary staples of Australia’s future economy - could take root. This contributed to the increased level of self-sufficiency in terms of food production, reducing Australia’s dependence on foreign imports. By end of Macquarie’s time ‘down under’, there were nearly 300,000 sheep in Australia, which served the white-settlers’ pockets and their bellies well. However, this had a truly devastating impact on the aboriginal population, who found that the sheep devoured the land on which the native kangaroo lived and pushed them into increasing conflict with land-hungry colonial farmers. 2) Macquarie rehabilitated. Historian Niall Ferguson highlights the continuities and the changes between Macquarie’s governorship and those of his predecessors. "Macquarie was every bit as much of a despot as his naval predecessors ... But unlike them, Macquarie was an enlightened despot. To him, NSW was not just a land of punishment, but also a land of redemption. Under his benign rule, he believed, convicts could be transformed into citizens." Governor Macquarie certainly aimed to ensure that the convicts could attain earthly salvation through hard work, obedience and good discipline. For every convict that was able to complete their sentence, a generous grant of 30 acres of land awaited them. Moreover, Macquarie allowed some convicts to undertake legal roles and aimed to improve the awful conditions aboard the penal ships that were used to transport the felons to Australia. 3) Macquarie was a Marmite figure. He certainly did not please everyone. Australia’s reformed criminals no doubt looked upon his munificent land grants positively. In addition, Macquarie’s contribution towards the planning and development of Australia’s early towns is undoubted. That these towns have stood the test of time constitutes Macquarie's enduring legacy. To this end, Macquarie was admired by those who viewed his developmental endeavours as a necessary prerequisite in the process of transition from a dedicated penal colony to a fully functional outpost of the British Empire. However, there were those in London who viewed Macquarie as financially wasteful, a misguided spendthrift and a colonial loose cannon, beyond the reproach or rebuke of his superiors in London. There were those in Australia who viewed Macquarie as being overly lenient on the convicts. His unswerving commitment to the provision of land grants was seen by some as a dangerous threat to the social status-quo and the entrenched privileges of Australia's 'free settlers'. Moreover, the indigenous aboriginal population continued to suffer significantly while Macquarie was governor as little of substance was done to reign in the settlers' lust for land or moderate the concept of terra nullius, which the British applied to Australia. Like Marmite, Macquarie was not to everyone's taste.

Thank you for reading. Feedback is always welcome! Patrick O’Shaughnessy (@historychappy) Co-Editor of Versus History The War of 1812 is something of a historical anomaly. The very fact that it is named after the year of its commencement is probably a tacit acknowledgement of the lack of enduring traction that it has had in the historical consciousness of its combatants, the British and the Americans. Of these two nations, the War of 1812 has (arguably) had a greater impact and legacy in the United States of America. For Britain, the War of 1812 was, for the most part, an inconvenient sideshow to the primary conflict of the early nineteenth century, the tussle with Napoleonic France. Prior to the convincing British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, the spectre of a potential naval invasion and subsequent conquest by France loomed large in the British national psyche. By the outbreak of the War of 1812 with America, Britain was acutely aware that Napoleon’s ground forces posed a grave threat to the balance of power in continental Europe, even though the prospect of a naval invasion of Britain itself had receded. Therefore, in terms of the British strategic paradigm in 1812, the war with America had to play second fiddle to that with France. It should be remembered that it was ultimately America that declared war on Britain, not the other way around, which is probably revealing in terms of which nation viewed the War of 1812 as most significant at the time. From the perspective of the newly formed United States of America, Britain’s attempts to regulate its global trade and impress its sailors amounted to an attack on its recently acquired sovereignty and nationhood. HMS Leopard firing on, boarding and subsequently impressing 4 sailors from USS Chesapeake in 1807 could be considered a direct and unabashed attack on America’s small navy and sovereignty. The mantra ‘Free Trade and Sailors Rights’ both fuelled and reflected the sense of grievance felt by some in America towards British actions. In 1812, President Madison authorised the first ever American declaration of war and an invasion of Upper Canada, which had been a British colonial possession since the conclusion of the French and Indian / Seven Years' War in 1763. This invasion marked the first offensive and official action of the War of 1812. While not intending to be an exhaustive account, here are three key learning points about the War of 1812, which may serve you well the next time you undertake a game of Trivial Pursuit! 1) Many will know and be familiar with the American national anthem, which since 1931 has been entitled the ‘Star Spangled Banner’, written by Francis Scott Key. Some might be surprised to learn that the lyrics of the anthem itself were actually inspired by the intense British naval bombardment of the American Fort McHenry in Baltimore, Maryland in 1814, which took place during the War of 1812. Therefore, the American anthem is actually the story of this British attack on America. Thus, the ‘bombs bursting in air’ were actually fired by the Royal Navy and the fact that in the morning ‘the flag was still there’ is a tribute to American resistance against the overnight shelling of Fort McHenry by the British. Perhaps ironically, a British composer, John Stafford Smith, wrote the melody of the American anthem. Moreover, it was part of a popular British drinking song at the time, with which many a contemporary Londoner would have been familiar in the numerous pubs and taverns of the English capital city. 2) The last time that the American Senate declared war was in 1942, against Romania. However, the War of 1812 is significant because it was the very first time that this had happened in the new nation’s history. Since the War of 1812, the Senate has passed a ‘Declaration of War’ on only ten further occasions in over 206 years. At the start of the War of 1812, the American army numbered only around 5000, relying heavily on the contribution of the state militia to bolster its ranks. Moreover, their Officer Corps lacked vital experience, with many of the revolutionary-era officers having retired. Today, American military personnel are stationed in over 150 countries around the world, highlighting the scope of U.S international involvement. In addition, by 2017 U.S military services boasted nearly 1.3 million trained personnel, with a substantial reserve component in addition to this. Much has changed in the 206 years since the War of 1812! 3) The War of 1812 was the first time that the American homeland was invaded. The White House in Washington D.C was burnt by British troops on 24 August 1814 as a punitive response to American forces burning the British Governor’s residence in York, Ontario. The next major attack to punctuate the consciousness of American’s was the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, some 46,357 days later. To conclude the War of 1812, the Treaty of Ghent was signed on 24 December 1814 by British and American representatives. However, whilst the War of 1812 was inconclusive and ended in a draw, there were some significant outcomes. Canada was never to join the United States of America and embrace republicanism; Queen Elizabeth II is the Queen of Canada as well as the Queen of the United Kingdom. Furthermore, rather than expanding north following the War of 1812, American expansionism adopted a westward trajectory. By 1840, well over a third of Americans lived to the west of the Appalachian Mountains. Considering that King George III had prohibited settlers in the former Thirteen Colonies from such expansionism in 1763, this represents an important development for the ‘land of the free and the home of the brave.’ If you have enjoyed this blog post, you might also fancy checking out the Versus History Podcast on the topic, which can be found here. Thank you very much indeed for reading. If you have any queries, comments, questions or corrections, please do get in touch! Patrick O'Shaughnessy (@historychappy) Co-Editor of Versus History |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed