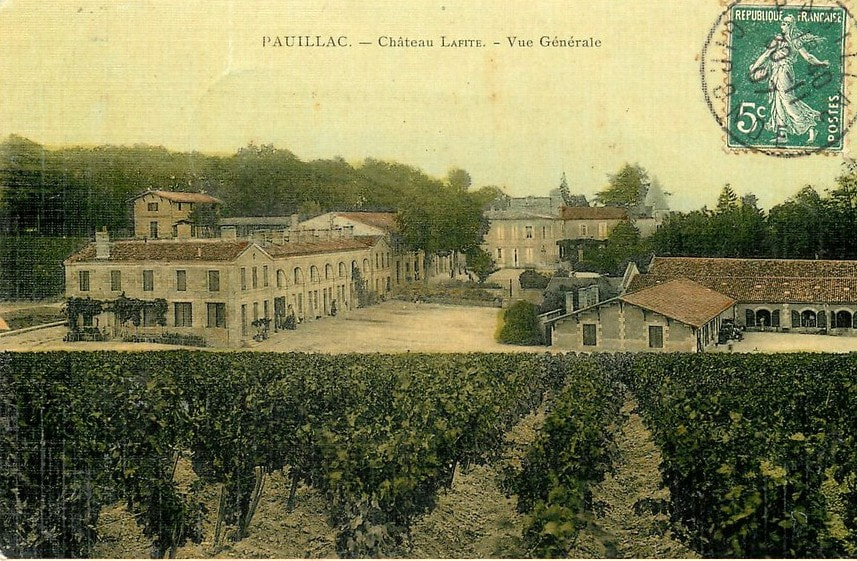

Executive director of trance hotels, graduate of École Hôtelière de Lausanne, and certified Court of Master Sommeliers, Suryaveer singh, takes us through the incredible history of wine.Benjamin Franklin once said “Wine is constant proof that God loves us and loves to see us happy”. The world of wine has a dark and mysterious past filled with ups and downs which run parallel to our very own existence as humans. In the mid-1970s a group of Archaeologists, working in the ancient site of ‘Khramis- didi- Gora’ in present day Georgia, stumbled across an artifact which would augment our understanding of the drink we know as wine. The artifact was an 8,000 year old Neolithic jar with fine engravings of grapes on it, used as a vessel in which to crush wine grapes and brew the delicate liquid which represented the terroir and love of the land. Such is the history of wine that it is intertwined with humanity’s history- wherever a civilization was set to thrive and flourish, the evidence of wine being grown is present. From the very moment the Ancient Chinese in 6000 BC discovered the art of fermenting crops into alcohol, humanity has twisted and turned alcohol recipes to suit palates for different ethnicities - be it beer or fortified rice wine. However, the terrain of modern-day Europe turned out to be ideal to grow wine through grapes and thus started the friendship of the Homo Sapien with wine. ‘Khramis- didi- Gora’ wine jug Wine seemed to serve numerous purposes for man - it was a safer to consume beverage over water, it was relatively easy to grow and consume, it was a valuable barter item, it was an ideal beverage to enjoy with food, the drink could be stored for longer periods and all sections of societies enjoyed it. The appreciation of wine in society is made visible with engravings of how to make it in the Pyramids of Giza in 2580 BC: King Tut’s tomb had countless wine jars for him to take to the after-life. On 197 occasions, the Old Testament mentions wine and refers to the beverage as ‘the blood of Christ’. Caesar used to command his mighty Roman army to consume up to 3 litres of wine a day/per soldier. Even Leonardo da Vinci didn’t shy from placing Jesus’ hand reaching for a glass in his iconic ‘The Last Supper’. Wine plays an integral part in mapping the history of Europe. Wine was introduced to the Mediterranean – present day Italy – by the Phoenicians in about 1550 BC, and the Roman Empire brought the crop from there to France. Throughout this time, the local population, through trial and error, figured out the most perfect and fertile plots of land to grow and perfect wine. One can examine the history of the renowned vineyards of Bordeaux in North Western France, which were historically under swamp water but drained by Dutch engineers in the 1600s’, as an example. The Dutch eventually farmed this land and turned it into a gravel and clay based soil – an ideal combination to grow award-winning wines. This new soil happened to bear fruit for the best wine making regions of Haut Medoc, and for wineries like Chateau Margaux and Chateau Lafite, which went on to be recognized by Napoleon and eventually the world as some of the greatest wines of our times. Chateau Lafite Winery The Romans perfected wine maturing in barrels along with the usage of hardened glass to protect the delicate liquid and showcase its most pure character. With wine thriving in Europe thanks to the Renaissance, the beverage was soon exported across the continent and throughout nations further afield through colonization. The discovery of the Americas, South Africa and Australia in the 1600s saw settlers bringing their favorite vines to new shores – George Washington being an avid wine grower himself. The New World, as it was referred to, had less rain and strong summers, which helped to ripen the fruit and bring about a more fruity flavored taste compared to the more mineral flavors in the European mainland. The 17th century was a seminal year for grape wine, with a sparkling variety of the beverage being introduced through sheer chance by a Christian monk named Dom Perignon in the Northern French town of Champagne. The world-of-wine now had a beverage to mark celebratory occasions. In 1703, tensions between the French and the British led to the development of Portugal growing wine of their own to feed the demand of Anglophiles. Portugal and Spain’s wine culture was disrupted under the rule of Islamic conquerors from 792AD to 1492AD. Greek youth using an 'oinochoe' or wine jug. 490-480BC The history of wine, however, does have a dark side. The beverage almost met its demise in the period from 1860 to 1890 due to an insect named Phylloxera which would chew the vines and ruin the fruit. Wine production from all countries dropped to a quarter in this period and with the growing popularity of alcoholic spirits, the wine market neared collapse. The industry finally figured out how to evolve their vines to withstand the bug and started to focus on the more common grape varieties of today- Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. The 20th century gave the industry a new challenge: with growth of the global population from 1.6 Billion in 1900 to 6.1 Billion in 1999, wine growers had to increase supply and adopt technology to rid themselves of archaic methods in order to improve their yield and quality. Two world wars caused a drop in production: the vineyards of Champagne were scenes of battle trenches, and cellars were looted. The state of Alsace in France, bordering Germany, exchanged occupation between the two warring countries, which resulted in the region producing German Rieslings with French finesse still to this day. The United States’ wine industry faced a devastating blow in the 1920s thanks to prohibition, which saw century-old vines uprooted and discarded. The industry lay dormant and discouraged until the 1960s. In 1966 an American called Robert Mondavi invested large sums of money to kick-start his very own winery in Napa, California. Mondavi’s winery encouraged others to follow suit and thus the golden age of New World wines began, with Californian wines often defeating their French superiors in blind tasting competitions. The New World, which comprised of non-European nations, adopted new techniques and methods such as temperature-controlled vats to ensure wine quality and screw caps to appeal to a new market. Today the New World produces more wine than any other single country. In 2019, the $423 Billion a year industry is at an exciting stage with strong demand from cash-rich China, overtaking the markets of Britain and France. With technology, wine growers are aiming to grow the grape in regions where, previously, none would have been deemed possible thanks to their long summers – India, China and Indonesia. Whatever we may see in the future, with global warming and the advent of artificial intelligence – wine will continue to remain man’s true companion, to sit beside him as one enjoys the fruits of life.  Suryaveer Singh, Executive Director of Trance Hotels Instagram: curious_sommelier

1 Comment

Trevor Marriott is a retired British Police murder squad detective who was involved in the investigation of many murders, as well as assisting in the investigation of many other major crimes throughout his long and distinguished police career. In 2002 he commenced a cold case re-investigation into The Whitechapel Murders of 1888 which were attributed to a killer known as Jack the Ripper. The results of that investigation have now not only dispelled, but shattered the myth that has been Jack the Ripper for 130 years. Those results are published in his book “Jack the Ripper-The Real Truth” In 2015, Trevor was commissioned by Merlin Entertainments, owners of The London Dungeon, and many other worldwide tourist attractions to re script the Jack the Ripper attraction in London, which now includes the results of his investigation. He is also the successful author of other books, both fact, and fiction and now travels the length and breadth of The UK, and the rest of the world giving audio visual lectures on not only Jack the Ripper but many other varied and interesting topics. His current list of other published books are; “The Evil Within -The World’s Worst serial Killers” 2014 “Prey Time” 2014 “Myths and Mysteries- The Real Truth” 2015 “Sherlock Holmes-The Final Chapter” 2017 “Pirates of the Caribbean- The Real Truth” 2017 For further information go to www.trevormarriott.co.uk Lars D. H. Hedbor will be the Special Guest on Versus History Podcast #30. The blog post below is by Lars himself, in advance of the release of his new book. Our image of the American Revolution is too often reduced to a caricature of white men in powdered wigs prancing about the countryside, quoting Jefferson and Paine in between picturesque set-piece battles with the vile Redcoats. Exploding that myth, my new historical novel The Freedman: Tales From a Revolution - North Carolina reveals the previously untold story of how former slaves made themselves indispensable to the success of the Revolution in North Carolina. The Freedman tells the story of Calabar, brought from Africa to North-Carolina as a boy and sold on the docks as chattel property to a plantation owner. Abruptly released from bondage, he must find his way in a society that has no place for him, but which is itself struggling with the threat of British domination. Reeling from personal griefs, and drawn into the chaos of the Revolution, Calabar knows that one wrong move could cost him his freedom—or even that of the nation. I was inspired to write The Freedman when I came across a news report about the former mayor of Greenville, North Carolina, who discovered that his African-American ancestors had actually fought on the patriot side. I immediately felt compelled to discover what that experience had been like. The more I learned, the more I knew that I had to tell the story of their vital contributions to the independence and liberty of a society that barely even tolerated their presence. My first novel, The Prize, was published in 2011, followed by The Light in 2013, and The Smoke, The Declaration, and The Break in 2014; The Wind was published in 2015, The Darkness in 2016, and The Path in 2017. Each book is a standalone novel, looking at the experience of the American Revolution from a different colony – including some usually ignored for having the poor judgment of not being part of the original thirteen.

I have also written extensively about this era for the Journal of the American Revolution, and appeared as a featured guest on the Emmy-nominated Discovery Network program The American Revolution, which premiered nationally on the American Heroes Channel in late 2014. I also appeared as a series expert on America: Fact vs. Fiction for Discovery Networks, and was a panelist at the Historical Novel Society’s 2017 North American Conference. The Freedman was released by Brief Candle Press on May 31st, 2018, and will retail for $12.99/€12.99/£9.99 in paperback through all online booksellers, and for $5.99/€5.99/£4.99 in electronic book format, through all major ebook providers. For links to all of my books, visit my Web site at http://larsdhhedbor.com/. Follow me on Twitter @LarsDHHedbor for daily tweets about #TodayInHistory in the #RevWar, and see my page on Facebook at http://facebook.com/Lars.D.H.Hedbor/ to learn about the latest news about my work. When Versus History kindly asked me to submit a blog post I immediately thought about the threat of revolution in Britain from 1789-1848. This period has fascinated me since my undergraduate days and now I run a course on the subject for the WEA. Sadly, I don’t have the space to cover the entire sixty-year era here. The good news is I can focus instead on the story and some of the historiography of what is possibly the most interesting period, one when revolution seemed possible but did not happen: the “heroic age of popular radicalism” (E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, 1963) from 1816-20.

This five-year period includes a public campaign for parliamentary reform running parallel with risings in obscure northern villages (inspired, depending on who you believe, either by government agents or a revolutionary underground), attacks on demonstrations, legislation banning public meetings, and alleged coups d’état culminating in treason trials. The key question arising from all this drama relates directly to the credibility of the revolutionary threat: was it merely the invention of enterprising government agents, or did a revolutionary danger actually exist? Thompson’s The Making suggested the existence of an underground radical thread linking the British Jacobins of the 1790s to 1820. This tradition was harboured and nurtured in the manufacturing districts of the North, finding expression first in clandestine movements of the 1790s, then merging with trades unions via the Combination Acts. After a brief lull came the Luddites, and then finally the widespread campaign for parliamentary reform following the Napoleonic Wars - a campaign which involved open public agitation and covert revolutionary activity. The thread died with the Cato Street Conspiracy of 1820, the last of the proposed Jacobin coups d’etat (the first was in 1803, the “Despard Plot”, the second in 1816 at Spa Fields in London). Ten years later, Thomis and Holt’s Threats of Revolution in Britain 1789-1848 (1972) was in little doubt about the nature of any threat: “The revolutionary underground… seems to have been almost the determined creation of stubborn, short-sighted governments”. This is a view which has its origins in the aftermath of the 1817 Pentrich Rising, when the Leeds Mercury exposed a government spy (“Oliver the Spy”) said to have been responsible for inciting rebellion across the North. Fabian historiography of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries would find much to commend in the story of a ruthless administration sending agents provocateurs to poison the minds of sensible sober Englishmen. Three years later there were echoes of Oliver in the activities of another spy, George Edwards, during the Cato Street Conspiracy. So, amongst other concerns, Thompson’s critics had responded by citing government use of spies to encourage rebellion – allowing them to portray any discontent as the work of isolated, misguided and easily manipulated fools. And there the debate seemed to solidify into two competing and immovable sides. That is, until Edward Royle’s Revolutionary Britannia: Reflections on the threat of revolution in Britain, 1789 – 1848 (2000). Anybody interested in the years 1816 – 20 must read this book. Bringing new and old research together for the first time, Royle shows how a Thompsonian thread could be visible in the stories of men who claimed to have associations with revolutionary activity and in some cases were arrested and tried. Particularly illuminating is the case of John Blackwell, who led an attack on a Sheffield armoury in 1812. Blackwell reappeared four years later during a riot in Sheffield, the day after the alleged Spa Fields coup d’etat attempt in London. And then he put in a final appearance in April 1820 at the head of a crowd attempting to attack a Sheffield barracks on the same day as a rising in South Yorkshire was due to take place. As Royle asks, when considering the nature of the revolutionary threat from 1816-20: “Were ministers rather better informed than sceptical historians have sometimes liked to think?” Mike Towers (@Mike_Towers) Guest Versus History Blogger |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed