|

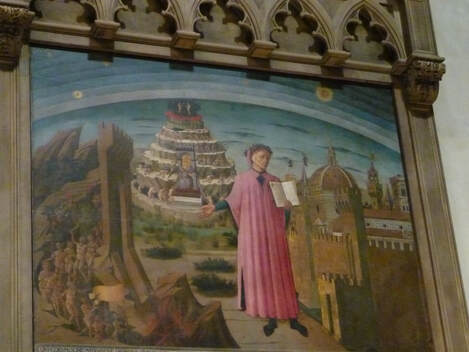

You can learn a lot of history on your travels and the reverse is also true: knowing some history will much enhance your enjoyment and understanding when exploring new places. In Florence this year, the talk is all about the 700th anniversary of the death of the medieval poet, Dante, and knowing something about him and the Florence of his day, would give you a focus if you were lucky enough to visit the city. Florence, capital of the Italian region of Tuscany, is best-known as the cradle of the Renaissance, centring around the time of artists like Donatello (1386-1466) and Michelangelo (1475-1564), but in fact many of the city’s most famous buildings pre-date that and were familiar to Dante, whose dates are 1265-1321. Dante’s reputation reaches far beyond Florence, for he is considered the greatest Italian poet of all time and the father of the Italian language, a man of immense culture, a poet, yes, but also an essayist, philosopher and politician. His ideas and his language are everywhere in Italian thought and speech today and the best comparison, albeit one from a later era, would be to say his influence on Italian culture is as great as Shakespeare’s on the English-speaking world. If you are in Florence for only a few days it can be difficult to prioritise what you want to see, but an itinerary built around places connected with Dante, or Dante Alighieri to give him his full name, would entail a varied and fascinating visit. If you begin in the area around the Duomo, or cathedral, then you are in the heart of Dante’s Florence, a medieval area full of narrow streets, little squares and the road, now called Via Dante, where he lived. The cathedral was begun in 1296 and we know that Dante used to sit nearby and watch the workmen building the beautiful green-and white marble facades and the world-famous dome, a construction nearly everyone at the time said would be impossible to engineer, but which was in fact achieved. The terracotta dome, brooding over the city, is the number one picture found on postcards from Florence today. Much of Dante’s biography is illustrated in this area. Next to the cathedral is the smaller, octagonal building built in a similar style as the cathedral, the Baptistery, where the babies of Florence – including Dante himself – were baptised from the 11th century onwards. It is famous today for its stunning gilded bronze doors, exquisitely sculpted with scenes from the Old Testament and so beautiful that Michelangelo later gave them the name which has stuck right up to today: the Gates of Paradise. To Dante, this building represented his home city and when he was later exiled for political reasons, it was for the baptistery most of all that he pined. In the cathedral itself, hangs a painting of Dante, by the artist Domenico di Michelino which tells more of his story. It shows him as the main figure in the setting of his best-known work, The Divine Comedy. The story tells of a journey from hell, through purgatory and on to heaven and all three settings are depicted in the painting. Two things are particularly striking: a close look at the part representing heaven will reveal that this is represented by the city of Florence – on the right-hand side you will see the dome; secondly, Dante is portrayed wearing a laurel wreath as a crown, the honour traditionally bestowed on poets in ancient Greece. Dante, exiled long before his death, was never honoured in this way, although he wrote in the Divine Comedy that he dreamed of returning to his home city one day and receiving the laurel wreath. Commissioned some 140 years after Dante’s death, the painting is an example of Florence, having shunned Dante during his lifetime, trying to reclaim him. The Casa di Dante – Dante’s house – is also in this medieval part of Florence, but all is not quite what it seems. Dante did indeed live in this street, in fact his family owned several properties here, but his house was destroyed by enemies in revenge for something he wrote in the Divine Comedy. Banned from his own city, and threated with death if he returned, Dante peopled the inferno, the hell of the first section of the work, with real life Florentine residents. They retaliated by wrecking his property. The rebuilt house, which does give a good idea of life in Dante’s day, is now a museum about his life and works. Nearby are buildings he would have known, such as the Torre della Castagna (Chestnut Tower), an 11th century defensive tower built to guard a nearby monastery and the tiny 10th century San Martino Church, just on the corner of the road where he lived. Places you can visit in other parts of the city bear witness to Dante’s later life. Piazza della Signoria is Florence’s other major square, the political centre, rather than the religious one. It was in the Palazzo Vecchio there, that Dante the politician took part in city assemblies and sat on councils and it is here, that still today, you can see his death mask. The Bargello today is Florence’s major museum of sculpture, but it had much grimmer beginnings as a court, prison and place of torture and it was here that Dante was sentenced to exile. The faction he had supported who wanted the city to be independent of the pope had lost and its rival, now ruling, faction, banished him. In later centuries, Dante’s reputation grew, in Italy and worldwide and Florence wanted to claim him back. He is buried in Ravenna, but there is a cenotaph for him in the Santa Croce church in Florence, which was installed in 1829. It depicts him in a pensive mood, captioned by words from his own writing: Onorate l’altissimo poeta’, or ‘In honour of the greatest poet.’ In 1885, a year after the unification of Italy, when national pride was a major theme, a statue of Dante was installed in the square outside Santa Croce. Again Florence, and Italy, were keen to have him to represent them. There is much history to enjoy from seeking out Dante in Florence. Firstly, his own achievements were of national and international importance: masterpieces like the Divine Comedy became known worldwide and influenced the literature of many other nations. Also, because he wrote it in the Tuscan dialect, rather than Latin, and it went on to be so widely read, he is seen as the father of the Italian language. Many of his idioms are used routinely today in modern Italian, the most famous example being the words said when a situation looks desperate: Lasciate ogne speranza voi ch’intrate: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here’, the inscription written above the gates of hell in The Divine Comedy. And secondly, the Florence of his day was one of Europe’s biggest cities, its wealth based on its great wool and textile industry, then on its merchants and bankers, the city where the first golden florin – named after the city – was minted and went on to become the most powerful currency in Europe. To visit Dante’s Florence is to understand medieval Europe better. And, happily for the traveller, much of the Florence he knew can still be seen today, in the city’s streets and churches, in its art, its architecture and its museums. You just have to know where to look! Further Information

Podcast City Breaks Florence Episode 04 - Dante’s Florence Reading Florence The Biography of a City by Christopher Hibbert The Divine Comedy by Dante Pocket Rough Guide to Florence Lonely Planet Travel Guide to Florence and Tuscany Eyewitness Travel Top Ten Guide to Florence and Tuscany Written by Marian Jones

0 Comments

Historical Fiction is a tricky beast: no other genre is expected to offer the ‘triple E’ of education, entertainment, and escapism. Lovers of historical novels will never forget the epiphany of reading THAT novel, which made them fall in love with a pen that brings the past back to life. In my case, I devoured vintage classics such as ‘I, Claudius’ or ‘Sinuhe the Egyptian’. Some authors create entirely fictional characters – think Bernard Cornwall, Patrick O’Brian, Margaret Mitchell, or Robert Harris, introducing their characters into global events. Others, such as Conn Iggulden’s ‘Genghis Khan’ trilogy, the Philippa Gregory Tudor- and War of the Roses novels, or even ‘Desiree’, the world’s second bestselling #HistFic ever, feast on the larger-than-life characters. These can be daunting examples – how can an author avoid the cold, hard re-telling of historical dates and facts as much as an unreliable, if not soppy romanticised version of events? ‘So how much fact is in this?’ people ask, sounding slightly suspicious, when hearing about my ‘Tsarina’ series. Both ‘Tsarina’ and ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ are the first novels ever about either, early, Romanov Empress. Given the mediatic omnipresence of Catherine the Great and the morbid fascination with the last, doomed Tsar Nicholas II, this seems unimaginable. How come, and how to set a stage rich enough for their stunning lives to act out? If my ‘Tsarina’ rose from rags to riches, morphing from serf to the first ever reigning Empress Catherine I of Russia, ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ Elizabeth, the only surviving sibling of Peter the Great’s fifteen children, in my new novel suffers an opposite fate: She falls from riches to rags, before rising triumphantly from rags to Romanov in one rollercoaster of a wild, seductive ride. This made writing about her a particular challenge: she acts far ahead of her time, and also daring beyond her sex. Determined to do things her own way, Elizabeth was a modern woman, even if her path was stony. Not even aged twenty, following her parents’ death, ‘Europe’s most lovely Princess’ – Louis Caravaque paints her looking like a young Marilyn Monroe, dewy-eyed and rosy-cheeked – found herself impecunious and isolated. Given the choice between a third-rate match – when neither the marriage of her sister or her numerous cousins inspired much confidence in marital relations in her – or to retreat to a nunnery, with a maimed and babbling hunchback dwarf as her sole company, Elizabeth did neither. I did research for a year before daring to write the opening sentence of ‘Tsarina’, the world’ ultimate double Cinderella story, describing the birth of a nation. A wide variety of reading bridged past and present, allowing to attempt an answer to the question: How were things REALLY like, especially for women living in a brutal, male dominated world, which offered little prospect beyond annual childbirth? I did my homework, reading everything from the classics such as Gogol, Dostoevsky, and Tolstoy – to the point where a name without patronym looks bland to me! – to letters from foreign envoys at court and travel diaries of a 17th century merchant to fairy tales – invaluable for understanding a people’s imaginary – and, last but not least, tomes such as Prof. Lindsey Hughes’ ‘Russia in the Age of Peter the Great’. The details provide a non-negotiable framework: clothes, food, furniture, travel and the aspect of cities and town. As for the historical background of ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’, the years following Peter the Great’s death set the stage for a brutal battle for the reign in Russia, a struggle for Russia’s very survival. The throne was orphaned three times in five years - a revolving door in these most complex times in the Russian history, which is rarely straightforward. The setting of both novels was like a loom a thousand strands strong, apt to weave a tapestry grand enough to fill the walls of the Winter Palace. Yet this historic background ought never to weigh on the story, but make it float instead. The challenge equals doing a split. Like in the Olympic Games, the setting is the Rhythm Dance, the fleshing out of the character and the flow of a pacey, fresh story the Free Dance. I take liberties with the language, though: my heroines are not stuck in some weird period-drama, but are women of flesh and blood, who speak modern English. ‘Sod the caviar!’ Why ever not? Careful, though – a medieval brain cannot be ‘computing away’, as I recently read it. Take heart! During research you will find the angle to reel a reader into his world and story. In his TED talk, the literary agent Jonny Geller says: ‘Readers are looking for a journey, from a place where they have not been, to a place they know not where...’ It should be the same for an author. In the case of ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’, this was discovering the terrible price my heroine had to pay for seizing power in Russia. Also, the rumours surrounding Elizabeth’s birthplace, Kolomenskoe Palace, were intriguing. It was said to be haunted by soothsaying, ill-willing spirits and rumoured to be a gate to time travel. How seductive to provide my heroine with a Delphic prophecy, which accompanies her life like a choker of dark pearls; guidance, and warning in one. My leading ladies were like Tut-Ankh-Amun, hiding in plain view. Finding them might have been an unbelievable stroke of luck; I prefer to think that I was destined to do so. Germans and Russians share a millennial history (My father grew up in the GDR) and ‘my girls’ lived as raw and fearless as I would like my writing to be. Despite hooped skirts, candle-light and sled-rides, both ‘Tsarina’ and ‘The Tsarina’s Daughter’ are thoroughly modern novels. My heroines breathe with their hearts, surviving wars, vicious female jealousies, and callous court intrigues of the highest order, making for a marriage of dreams of fact and fiction, and a sweeping epic cloaked in ice and snow.

'Tsarina' & 'The Tsarina's Daughter' @Bloomsbury Books Twitter: @Ealpsten_author Instagram: @ellenalpsten_author www.ellenalpsten.com |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed