|

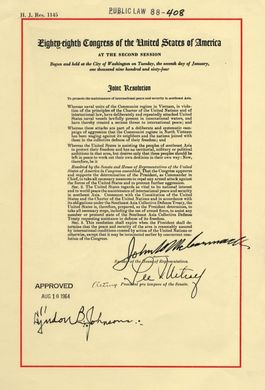

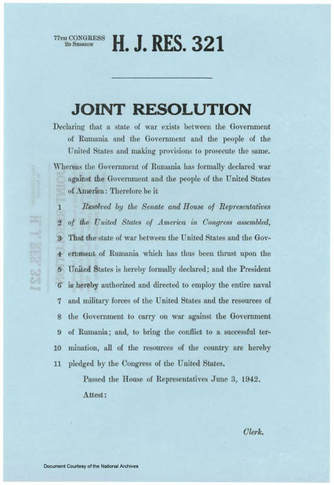

The ‘Tonkin Gulf Resolution’, August 10th, 1964 Our recent Versus History podcast was a fifteen-minute special in which Patrick asked me some quick-fire questions in the allotted time on one of my particular areas of interest. The area of interest that I elected to have questions fired at me upon was American involvement in the Vietnam War. For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by the Vietnam War. I am very much aware that the term ‘fascinated’ is perhaps wholly inappropriate a verb to employ when discussing an event in which countless numbers of people lost their lives, and one which still carries a present-day legacy of physical and emotional trauma, but it is, to me, the right word to use. It is entirely possible that my fascination was conceived during my early to mid-teens when I would spend school lunchtimes at a friend’s house watching (among a number of movies I wasn’t supposed to watch at such a tender age) the Oliver Stone film, Platoon. The horror of the conflict and the stark and complex differences between the ‘soldiers’ on both sides, as well as the differences between the American soldiers themselves, made for a jarring, unsettling viewing experience. The more I learned and, later, taught about American involvement in the Vietnam War, the more it became clear to me why it was so, enigmatic. Again, you may think this a terrible choice of adjective to describe an event of such tragedy and horror - and for the most part, you would be correct in your thinking, except that... Ask yourself this question: When did the Vietnam War begin? Go one further and ask yourself: When did American involvement in Vietnam begin? The enigma that I speak of is bound up in these two questions. It used to be that wars were a largely formal affair - war was declared, lines were drawn, sides were assembled, and battle commenced. The United States has not issued a formal declaration of war since June 4th 1942, which was against Rumania. Of course, to suggest that the United States has been entirely uninvolved in direct military conflict since 1942 would garner immediate incredulity. However, the fact still stands: the United States Congress (for it is only the legislature which can do so) has declared war ‘only’ eleven times in its history, starting in 1812 against the British, and ending in 1942 against the Rumanians. And therein lies the rub. As historians of conventional wars, we can place our finger on a date in a calendar, or a mark on a timeline and declare with the utmost of confidence, “Here, here is where the war starts!”. With the conflict in Vietnam, we can have no such confidence because we can do no such thing. US Declaration of War on Rumania, June 4th 1942 All of what we would call modern day Vietnam (as well as many of its surrounding neighbours - often referred to collectively as Indochina) had been colonised and ruled, almost without break, for hundreds of years by various foreign interlocutors - from China, to France, to Japan, back to France, and then - according to most Vietnamese - to the United States. Each subsequent incoming coloniser (for that is how they were most certainly viewed by the vast majority of the people of Vietnam) came into the country immediately upon the heels of the outgoing coloniser. In some cases, the outgoing invader was forced out by the incoming invader. In some cases, the invader was chased out by the Vietnamese themselves. In other cases - one of particular note - the outgoing occupier (a failing France) asked for assistance from someone they hoped would take on some of the burden of ruling Vietnam - the United States.

Since there is no declaration of war to which we can point as the ‘start’ of the war, then the language we employ must shift to accommodate the vagaries of a war without one. The term we generally use in our investigation is ‘involvement’. In many ways this word is a poor substitute for ‘beginning’ or ‘start’ - instead of making things clearer, the new semantic actually makes murkier the already murky water. Ask any Historian to determine the origin of a war, and expect a deep inhalation of breath before they begin. Ask any Historian about the origin of involvement in a war, and you had better tell your husband or wife that you’ll be late home for dinner. The reason? How do you quantify involvement? How do you qualify involvement? By what criteria do you judge involvement? What does involvement even mean? You know what I mean? Take a deep breath... Without a declaration of war, at what point would you consider America to be involved in Vietnam? If a president utters public phrases criticising French occupation of Vietnam, does that represent a public investment in the concerns of the country? If a president begins discussing who should rule Vietnam once World War Two is over and the Japanese are defeated, does this constitute American involvement? FDR did both of these things. If American soldiers, including Major Allison Thomas, as part of an OSS (Office of Strategic Services) mission had parachuted into North Vietnam to train Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh guerrillas to help prevent Japanese escape and gather intelligence, would this constitute American involvement in Vietnam? This happened in the dying days of World War Two, under President Truman. In order to guarantee French support in NATO, and to avoid a Cold War power vacuum being created by a French loss in Indochina (who were now fighting the Viet Minh), Truman authorised millions of dollars in financial and military assistance to the French. Would this be considered US military involvement in Vietnam? President Eisenhower gave billions of dollars worth of aid and provided 1500 military advisors to Diem (the leader of South Vietnam) who helped establish the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam). He even guaranteed that he would support Diem if he chose not to hold the free elections that had been called for under the Geneva Accords of 1954. Would this be considered involvement? Remember, at this point in time - 1954 - there are no American ‘boots on the ground’. When the French lose at the Battle of Dienbienphu in 1954 and decide to leave Vietnam for good, America already has a financial, military and ideological commitment to the security of South Vietnam. And yet… no war. When JFK, in 1956, gives a speech determining that ‘Vietnam is the place”, is he foreshadowing an increased involvement? When Kennedy becomes the President and increases financial and military assistance, including helicopters and pilot ‘advisers’, authorises the use of Agent Orange and Napalm, increases the number of military ‘advisers’ to 16,000 by 1963, creates the MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam), secretly sends Green Berets, and authorises the Strategic Hamlets Programme, is America involved? Remember, there are still no official US soldiers fighting and there is no Congressionally recognised war. When President Johnson convinces Congress to pass, what was known as, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, authorising presidential discretion in terms of a military response, is America involved? Is it involved at the point at which Operation Rolling Thunder begins, in 1965, bombing the jungles and villages of North Vietnam, dropping more ordinance than was dropped on Europe during the entirety of World War Two in the process? Is it involved when LBJ authorises an escalation of over half a million troops to assist the government of South Vietnam fight against the Vietcong and the Viet Minh? Exhausting, right? And remember, still no declaration of war by the US Congress. Thank you for bearing with me. Let me synthesise:

Where does this leave the student of American involvement in Vietnam? It leaves you with an interesting and unique opportunity: you get to choose both the meaning of the word ‘involvement’ and determine the point at which you consider the US to be involved. That’s what is so wonderful about the subject of History: provided you maintain an honest commitment to the evidence, you get to set the parameters of your investigation. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (@thelibrarian6) Co- Editor, Versus History

0 Comments

Lars D. H. Hedbor will be the Special Guest on Versus History Podcast #30. The blog post below is by Lars himself, in advance of the release of his new book. Our image of the American Revolution is too often reduced to a caricature of white men in powdered wigs prancing about the countryside, quoting Jefferson and Paine in between picturesque set-piece battles with the vile Redcoats. Exploding that myth, my new historical novel The Freedman: Tales From a Revolution - North Carolina reveals the previously untold story of how former slaves made themselves indispensable to the success of the Revolution in North Carolina. The Freedman tells the story of Calabar, brought from Africa to North-Carolina as a boy and sold on the docks as chattel property to a plantation owner. Abruptly released from bondage, he must find his way in a society that has no place for him, but which is itself struggling with the threat of British domination. Reeling from personal griefs, and drawn into the chaos of the Revolution, Calabar knows that one wrong move could cost him his freedom—or even that of the nation. I was inspired to write The Freedman when I came across a news report about the former mayor of Greenville, North Carolina, who discovered that his African-American ancestors had actually fought on the patriot side. I immediately felt compelled to discover what that experience had been like. The more I learned, the more I knew that I had to tell the story of their vital contributions to the independence and liberty of a society that barely even tolerated their presence. My first novel, The Prize, was published in 2011, followed by The Light in 2013, and The Smoke, The Declaration, and The Break in 2014; The Wind was published in 2015, The Darkness in 2016, and The Path in 2017. Each book is a standalone novel, looking at the experience of the American Revolution from a different colony – including some usually ignored for having the poor judgment of not being part of the original thirteen.

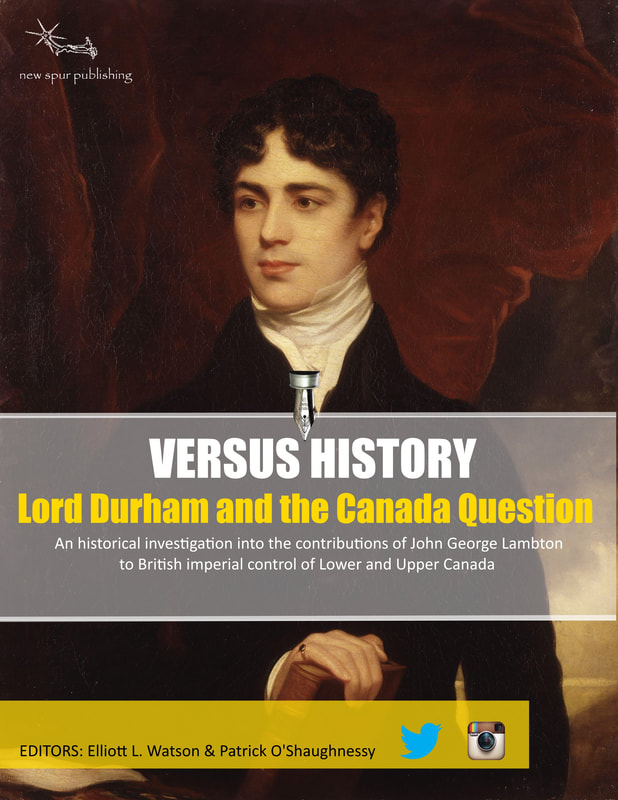

I have also written extensively about this era for the Journal of the American Revolution, and appeared as a featured guest on the Emmy-nominated Discovery Network program The American Revolution, which premiered nationally on the American Heroes Channel in late 2014. I also appeared as a series expert on America: Fact vs. Fiction for Discovery Networks, and was a panelist at the Historical Novel Society’s 2017 North American Conference. The Freedman was released by Brief Candle Press on May 31st, 2018, and will retail for $12.99/€12.99/£9.99 in paperback through all online booksellers, and for $5.99/€5.99/£4.99 in electronic book format, through all major ebook providers. For links to all of my books, visit my Web site at http://larsdhhedbor.com/. Follow me on Twitter @LarsDHHedbor for daily tweets about #TodayInHistory in the #RevWar, and see my page on Facebook at http://facebook.com/Lars.D.H.Hedbor/ to learn about the latest news about my work. Today marks the arrival of our second Versus History publication: Lord Durham and the Canada Question. Our previous publication, 33 Easy Ways to Improve Your History Essays, was written to help students navigate the difficult waters of historical writing; this time we have written an academic investigation into an integral part of British Imperial history. The rationale for writing about Lord Durham - often known as ‘Radical Jack’ - was simple: we found that Lord Durham’s contribution to British Imperial policy, particularly as it related to the Canadas, was woefully under served in the textbooks and presented a truly difficult challenge to students seeking to source readily available academic literature on the topic. Thus it was that we set our energies to uncovering the role of the enigmatic Lord Durham in the ‘Canada Question’.

Great Britain’s influence in North America was reduced in humiliating fashion by the American Revolutionary War (1775-83); the loss of the thirteen American colonies was a disaster for King George III and the metropole. However, British influence - though radically diminished - still remained in North America, albeit in a much diluted form and a more northerly location. Its reconstituted North American territory still contained New France - a product of the British victory in the Seven Years War over France and Spain. Among other territories, New France contained Lower and Upper Canada. When, in 1837, the British-controlled territories of Lower and Upper Canada erupted in open rebellion against the metropole, it seemed to some at the time that Great Britain was to suffer an unconscionable second colonial humiliation in the space of just over half a century. Although there is debate about just how serious these twin rebellions were to London’s dominion over the Canadas and, indeed, to the wider British Empire. Equally, the comparisons drawn between the revolution south of the border and those of Lower and Upper Canada, have proved uncertain. What is certain, however, is that Lord Durham was thrust into the centre of this ‘Canadian problem’. John George Lambton, Earl of Durham and Whig boulevardier, was cajoled by British Prime Minister, Viscount Melbourne, and even the young Queen Victoria, to take on the roles of Governor-General and High Commissioner of British North America. In this role, he was tasked with determining the causes of the twin Canadian rebellions and, crucially, proffer solutions. These solutions needed to achieve twin outcomes, both with high degrees of subtlety: placate Canadian dissatisfactions; maintain British rule. The central discussions rest here: what, if anything, did Lord Durham achieve in his brief time as the Governor-General/High Commissioner of British North America? Canada did not follow the revolutionary lead of its geographical cousin to the south and, in fact, became the very model of responsible government within the British empire. In time, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa would adopt similar models of government. However, just to what degree Lord Durham deserves credit for these developments, is where we must begin our investigations. In true Versus History style, Elliott will be asserting the contributions of Lord Durham were crucial to the settling of the ‘Canadian issue’, while Patrick will be challenging this argument with his own: that Durham’s involvement was minimal at best, and the ‘issue’ was a mere ‘trifle’ in the overall concerns of the British Empire. Pre-order the ebook format now, or download it from Amazon on the 17th, which is free for the first five days of publication, and discover - either as a student or a teacher - the contributions of the enigmatic Lord Durham to the ‘Canada Question’. Elliott L. Watson & Patrick O’Shaughnessy Co Editors and Authors of Versus History The Broadway musical ‘Hamilton’ has been an absolute smash hit, both in America and London. Even if one is not familiar with the historical context of the production, they may well have heard one of the catchy songs from the musical itself. Tickets for Hamilton are certainly not cheap - demand for seats has far exceeded supply! Along with appearances from the 'Founding Father' Alexander Hamilton, the production features three comical songs from the British King George III, who reigned from 1760 to 1820, directed at his troublesome and revolutionary colonial subjects on the other side of the Atlantic.

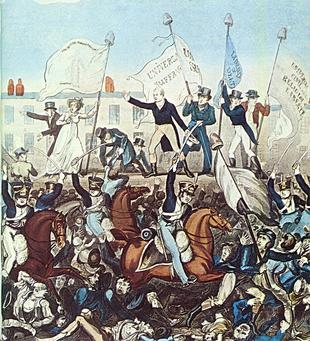

For many, this may well be the first time they have encountered George III as a historical actor. King George III did indeed support the raft of Parliamentary legislation aimed at bringing the American colonists to heel, notably under his Prime Minister Lord North in the turbulent 1770s. In this period, the Boston Massacre, the Tea Act, the Boston Tea Party and the ‘Coercive Acts’ heightened tensions and galvanised the wrath of American Patriots in the Thirteen Colonies towards British rule. Moreover, Thomas Paine labelled George III as the ‘royal brute’ in his 1776 pamphlet ‘Common Sense’, while the Declaration of Independence of the same year accused George of trying to establish an ‘absolute tyranny’ in British America. All in all, a pretty damning critique! The validity of these claims is, of course, subject to debate. The musical Hamilton has certainly brought these issues back to the forefront of public and historical consciousness. But, there was more to King George III than America and tyranny. George III was the first of the Georgian monarchs to style himself as a proud British - as opposed to a Hanoverian - King. English was his first language, not German, unlike George I and II. Indeed, George III never even visited his throne in Hanover. He took a great interest in the art of Kingship, writing numerous essays on the topic as an adolescent. George had a particular penchant for farming and a keen interest in the system of enclosure that was engulfing England at the time - hence his nickname 'Farmer George'. In 1769, George's thirst for knowledge resulted in him building the Royal Observatory in Richmond, in which he took great pleasure. George was - by all accounts - committed to his large family and his wife, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, who lent her name to Charlotte, North Carolina (which, incidentally, Lord Cornwallis identified as a ‘hornets’ nest of rebellion’ during the American Revolution). George III may have been the last King of America, but he was also the first King of Australia, reigning over his Kingdom during a time of vast social, economic and industrial change. Few would doubt that George was a ‘hands-on’ sovereign, taking great pride and an intense interest in the ruling of his realm. He is Britain’s third longest-reigning monarch, behind Victoria and Elizabeth II. He was, perhaps, the last British sovereign to exercise bona fide executive power. His son, the Prince Regent and subsequently King George IV from 1820 to 1830, was certainly a great deal less popular with the British people than his father had been. Mental illness incapacitated George III for the last years of his life - a fact which is directly referenced in the songs by George III in Hamilton the musical. Hopefully, the musical itself will serve to inspire those interested in the production and historians to learn more about the ‘Mad King’. There was - whatever your opinion on King George III - certainly more to him and his reign than America and mental illness. I would love to hear your thoughts! Patrick O’Shaughnessy (@historychappy) Co-Editor of Versus History When Versus History kindly asked me to submit a blog post I immediately thought about the threat of revolution in Britain from 1789-1848. This period has fascinated me since my undergraduate days and now I run a course on the subject for the WEA. Sadly, I don’t have the space to cover the entire sixty-year era here. The good news is I can focus instead on the story and some of the historiography of what is possibly the most interesting period, one when revolution seemed possible but did not happen: the “heroic age of popular radicalism” (E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, 1963) from 1816-20.

This five-year period includes a public campaign for parliamentary reform running parallel with risings in obscure northern villages (inspired, depending on who you believe, either by government agents or a revolutionary underground), attacks on demonstrations, legislation banning public meetings, and alleged coups d’état culminating in treason trials. The key question arising from all this drama relates directly to the credibility of the revolutionary threat: was it merely the invention of enterprising government agents, or did a revolutionary danger actually exist? Thompson’s The Making suggested the existence of an underground radical thread linking the British Jacobins of the 1790s to 1820. This tradition was harboured and nurtured in the manufacturing districts of the North, finding expression first in clandestine movements of the 1790s, then merging with trades unions via the Combination Acts. After a brief lull came the Luddites, and then finally the widespread campaign for parliamentary reform following the Napoleonic Wars - a campaign which involved open public agitation and covert revolutionary activity. The thread died with the Cato Street Conspiracy of 1820, the last of the proposed Jacobin coups d’etat (the first was in 1803, the “Despard Plot”, the second in 1816 at Spa Fields in London). Ten years later, Thomis and Holt’s Threats of Revolution in Britain 1789-1848 (1972) was in little doubt about the nature of any threat: “The revolutionary underground… seems to have been almost the determined creation of stubborn, short-sighted governments”. This is a view which has its origins in the aftermath of the 1817 Pentrich Rising, when the Leeds Mercury exposed a government spy (“Oliver the Spy”) said to have been responsible for inciting rebellion across the North. Fabian historiography of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries would find much to commend in the story of a ruthless administration sending agents provocateurs to poison the minds of sensible sober Englishmen. Three years later there were echoes of Oliver in the activities of another spy, George Edwards, during the Cato Street Conspiracy. So, amongst other concerns, Thompson’s critics had responded by citing government use of spies to encourage rebellion – allowing them to portray any discontent as the work of isolated, misguided and easily manipulated fools. And there the debate seemed to solidify into two competing and immovable sides. That is, until Edward Royle’s Revolutionary Britannia: Reflections on the threat of revolution in Britain, 1789 – 1848 (2000). Anybody interested in the years 1816 – 20 must read this book. Bringing new and old research together for the first time, Royle shows how a Thompsonian thread could be visible in the stories of men who claimed to have associations with revolutionary activity and in some cases were arrested and tried. Particularly illuminating is the case of John Blackwell, who led an attack on a Sheffield armoury in 1812. Blackwell reappeared four years later during a riot in Sheffield, the day after the alleged Spa Fields coup d’etat attempt in London. And then he put in a final appearance in April 1820 at the head of a crowd attempting to attack a Sheffield barracks on the same day as a rising in South Yorkshire was due to take place. As Royle asks, when considering the nature of the revolutionary threat from 1816-20: “Were ministers rather better informed than sceptical historians have sometimes liked to think?” Mike Towers (@Mike_Towers) Guest Versus History Blogger |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed