|

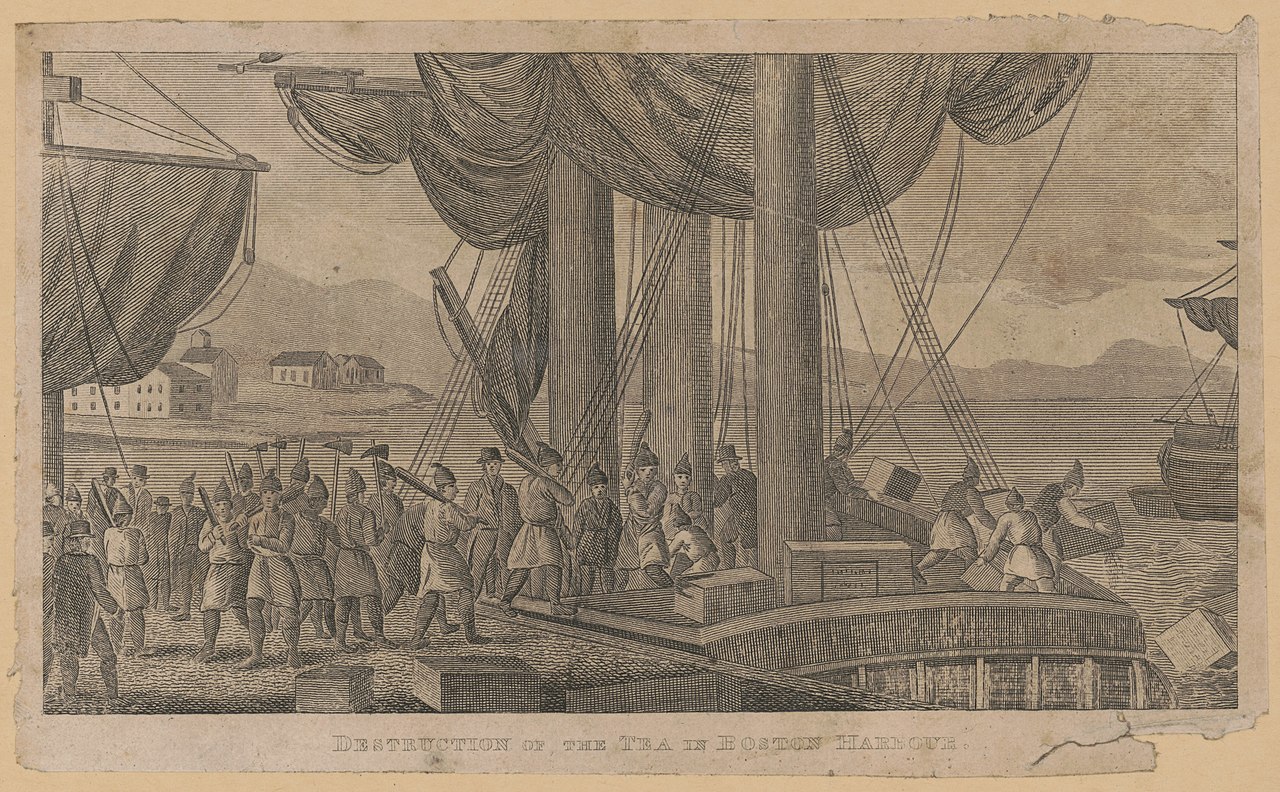

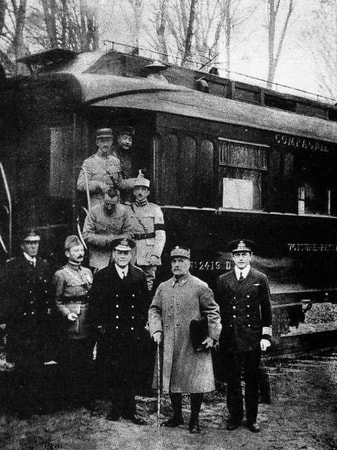

WORDS BY Anthony Ruggiero The American Revolution marked a turning point in the lives of colonists living in America who, after years of perceived mistreatment by the British, finally declared their independence. Although this separation from Britain was meant to benefit all those who advocated for it in the colonies, the results for American women offered no discernable improvement in their lives. Women were often criticised for their attempts at political participation. Additionally, women were forced to rely on their male counterparts for such things as landholding. Furthermore, although it could be argued that women used their spouses as vehicles to promote their political agenda, their reliance on their spouse was a representation of the gender barriers that existed during the time period. Women were also subjected to brutal treatment that was emblematic of their subordinate role in society. The Boston 'Tea Party' (Popular Graphic Arts [Public domain]) Throughout the events of the revolution and thereafter, women actively participated in promoting the agenda of revolutionists and unsuccessfully advocated for political recognition. For example, in 1775 Providence, when tea was being burned in opposition to Britain’s tea tax, women actively participated in the protest.[1] The Virginia Gazette article, Providence Women Burn Tea, recognized women’s participation within the protest, however it perpetuated a stereotype that women have an “evil tendency of continuing the habit of drinking tea.”[2] Additionally, the article also used a negative description of women to represent the burning of the tea as the “funeral of Madam Souchong.”[3] The article’s description perpetuates the contemporary societal view of women as ‘low’; as prostitutes.[4] Additionally, women’s attempted involvement in politics was also scrutinized. For example, Jane Adams advocated for the rights of women to be recognized in the new nation to her husband, congressman, John Adams, stating that women would cause a “rebellion” if their voices were not heard[5]. In response John Adams described her boldness as laughable, thus showing his disregard for her claims.[6] The Virginia Gazette discusses the British Taxation of the Colonies (Alexander Purdie [Public domain]) Although it can be argued that some women, as part of the social elite in society, were able to promote their political views by using their status, there reliance on their male counterpart also demonstrated their role remained as inferior. For example, a land sale by Anne Holden, a member of the Daughters of Liberty, to four men can be viewed as way to insert herself into the political framework, since women were unable to vote despite the size of their landholding[7]. Through giving her land to these four men, it can be argued that she sought to influence the men’s voting choice. However, this action also showed the reliance of women on the male gender to promote a female political agenda. Lastly, women during this period were subjected to brutal treatment. For example, Mary Philips described being raped by a British soldier who claimed she was secretly working with “rebels.”[8] Despite the promotion of female stereotypes and male oppression, many women continued to actively participate in promoting the agenda of revolutionists and advocated (unsuccessfully) for political recognition. For example, The Daughters of Liberty were a political group that surfaced in response to British taxation in the colonies during the American Revolution[9], in particular the Townshend Acts of 1767, which were a series of measures that imposed customs duties on imported British goods such as glass, paints, lead, paper and tea. According to Carol Berkin’s film, Women as Major Participants in the Revolutionary War, women took a political stance by burning tea, and instead of buying English cloth, they would create their own, which became known as "Liberty Cloth.”[10] Although a good majority of women were unable to leave their homes during the Revolution because they were expected to take care of their children, this time period resulted in what would be known as ‘republican motherhood’. This term applied to women who were primarily educated in order to help educate their children in the ways of ‘moral living’.[11] Women also played a pivotal role in influencing their children’s political views.[12] President Thomas Jefferson remarked, "I thought it essential to give [my daughters] a solid education, which might enable them, when they become mothers, to educate their own daughters, and even to direct the course for sons, should their fathers be lost, or incapable, or inattentive."[13] During the Revolution, women also began questioning their inferior status in relation to their husbands. Many women published poems citing their frustrations and their desires to be free. For example, one line from a poem read, “That woman, dear woman, shall ever be free. Nor more shall the wife, all as meek as a lamb.”[14] This time period spawned rhetoric of freedom from both Great Britain, as well as in society for women. The American Revolution was supposed to liberate all those colonists of European descent from oppression, but instead only highlighted the oppression women faced within early American society. Despite attempts to participate in politics, women such as Jane Adams, were still lambasted for their attempts. Furthermore, women were forced to rely on men within the upper classes of society in an attempt to promote their political views. While women attempted to succeed, societally and politically men benefitted.  Anthony Ruggiero is currently a High School History Teacher in New York City, New York. In addition to teaching, he has been published in several magazines, such as History Is Now, Historic-UK, Tudor Life, Discover Britain, and The Odd Historian. Anthony has also written for the Culture-Exchange blog, and The Freelance History Writer blog. His work can also be viewed on his Twitter handle: @Anthony10290122 [1] Providence Women Burn Tea, 1775. In Norton, Mary Beth. Major Problems in American Women’s History. Fifth Edition. Houghton Mifflin, 2014, 112. [2] Providence Women Burn Tea, 1775, 112. [3] Ibid, 113. [4] Ibid, 113. [5] Ibid, 113. [6] Ibid, 114. [7] Ibid, 120. [8] Ibid, 116 [9] Rebecca B. Brooks, The Daughters of Liberty: Who Were They and What Did They Do? History of Massachusetts, 2017. [10] Carol Berkin, Women as Major Participants in the Revolutionary War, 2014. [11] Lauren M. Eleuteri, Patriots in the kitchen: The role of Republican motherhood in Jeffersonian America. Retrieved from http://elonuniversity.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15446coll2/id/36. [12] Patriots in the kitchen: The role of Republican motherhood in Jeffersonian America. [13] Ibid. [14] Tho’ husbands are tyrants, their wives will be free. New York Journal, 1770.

0 Comments

If you are waking up right now, chances are you have had, what clinicians term, one period of consolidated sleep. That is, you went to bed yesterday evening and awoke the following day - this morning. In most parts of the world - particularly the industrialised world - consolidated sleep is the norm. By and large, our patterns of sleep and wakefulness (known as our circadian rhythm) are governed by two things: the cycle of nighttime and daytime; the daily demands on our time. The former is mandated by the movements of the planets (not much we can do about that), the latter is determined by a multitude of factors, perhaps the most significant being the daily work that we have to do. In a sense, for the vast majority of people, we don’t have much control over this either. The Industrial Revolution and state-sponsored education have tended to organise the daily routines of most people around the world, meaning that - exceptions notwithstanding - we carry out our ‘work’ during one continuous block during the day and sleep in one continuous block at night (if we are lucky). It was not always the case. In fact, until relatively recently your ancestors would most probably have maintained a bi-modal sleeping pattern. They had two sleeps a night. In At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, Roger Ekirch’s revelatory investigation into the social history of what people around the world do at night, a rich and varied trove of evidence from across the centuries and the globe, suggested that we had a ‘first sleep’ and then a ‘second sleep’. The first sleep began a couple of hours after the sun went down and lasted for 3-4 hours. After an hour or so of wakefulness (more on this in a moment), people went back to sleep for another 3-4 hours. During this period of wakefulness between the first and second sleeps, evidence abounds that people did either what was necessary - chopped wood, prepared food, prayed and such - or what was enjoyable - read, talked with bedfellows, had sex and so on. According to Ekirch, the surprising point in his discoveries is not that this practice seems to have been almost entirely forgotten in the post-industrialised world, but that it was such a commonality - references abounding in plain sight - in the first place. In England, prior to, and even during, the early phases of the Industrial Revolution, records of first and second sleeps are abundant and exist without any attention being drawn to their being in any way unusual. That’s because, according to Ekirch, they weren’t. In 1840, Charles Dickens dropped a ‘casual’ mention into Barnaby Rudge, “He knew this, even in the horror with which he started from his first sleep, and threw up the window…” Ekirch opens his 2001 paper, Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles, (out of which his book, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past was developed), with journal notes made by the Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson. These notes, written about his time spent camping and hiking through the Cévennes in France in 1878, describe with great poetry what he calls “the stirring hour” and “...this nightly resurrection” - that interval between sleeps which, even by Stevenson’s time, was largely a thing forgotten to history. It is a poignant opening to a piece of research that ‘rediscovered’ a practice which, to your ancestors, would almost certainly have been the norm. Robert Louis Stevenson takes his 'first sleep' in Cevannes WHY did we sleep twice? There have been suggestions that bi-phasal sleep became lodged in western Europe because of the requirements of early Christianity - monkish orders rising during the darkened hours to recite verses and pray - and that this embedded itself in European Catholicism which, in turn, promoted the same such nightly devotions from all strata of society. According to Ekirch, this can’t be the root of segmented sleep, because the very practice not only predates early Christianity, it existed across the world in areas which were, until relatively recently, untouched by Christian missionaries and religious conquistadors. Just why we took two sleeps at night is a complex question, linked perhaps to the dangers our ancestors (and not even to distant ones at that) faced by sleeping through the night - from predators to criminals. Night could be, it must be remembered, a terrifying time for all, dense as it might have been with frightful superstitions, religious paranoia, and the very real criminals that moved unseen. The night time was literally and metaphorically a time when the disreputable elements of life emerged: “Associations with night before the 17th Century were not good," he says. The night was a place populated by people of disrepute - criminals, prostitutes and drunks.” (Kolovsky, Craig.) Breaking sleep, as unnatural as it may seem to us now, could be fundamental to the survival of our ancestors. Sleep was a much more vulnerable state for our ancestors to have to endure than for most of us today. Unless the moon was visible at night, the darkness of the pre-industrial world would have been absolute. When people actually took to their beds for their first sleep was, in part, also related to the darkness because, as Professor Ekirch plainly stated in Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies:

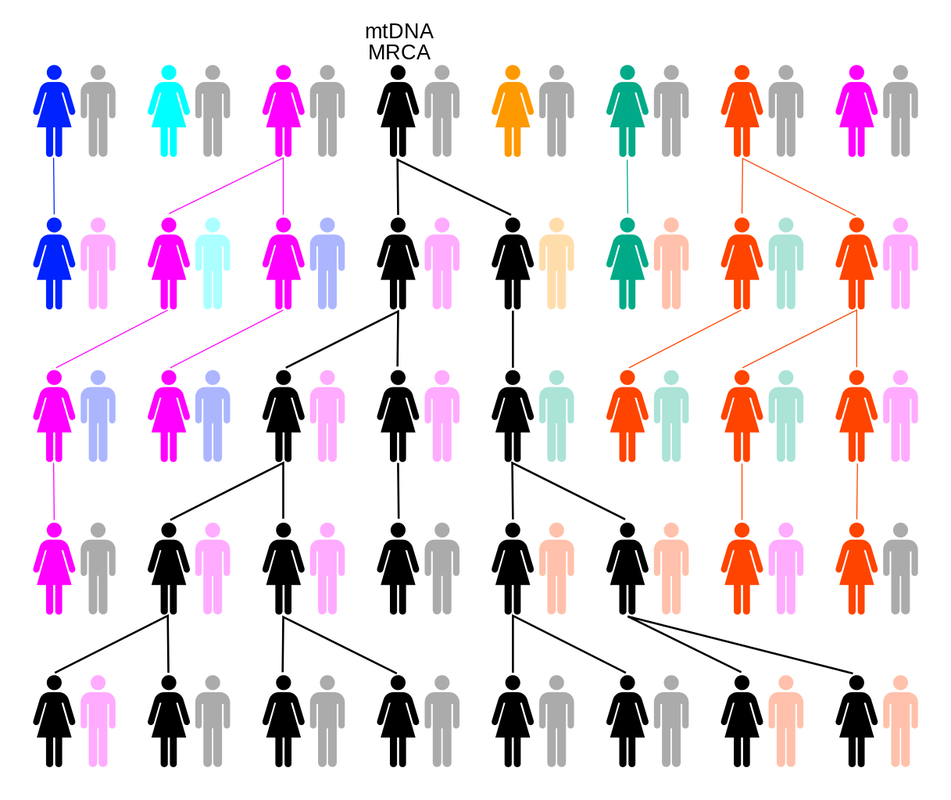

“As in many preindustrial cultures, sleep onset depended less on a fixed timetable than on the existence of things to do.” Since pre industrial England relied so heavily on the daylight to accomplish these ‘things to do’ - our daily toils - once the night arrived it would have been near-impossible to conduct anything except the least arduous of tasks, such as talking, eating, or sleeping. If the work had been accomplished for the day - in the hours of light during which it was possible to accomplish it - then the timing of the ‘first sleep’ need not have been rigid. However, it cannot be overstated just how utterly devoid of light the night could become in a world before the Industrial Revolution. Unless the moon rendered otherwise, darkness would have been near absolute for anyone who could not afford artificial light - candles, oil lamps and such. And this is where the answer to the question of why we no longer have two sleeps at night is to be found: artificial light. Perhaps the more important question isn’t really why we used to have two sleeps and a ‘break’ but why we stopped the practice. The wealthier classes were perhaps the first to move away from the prehistoric ‘two sleep’ pattern because of their earlier access to artificial light - candles, oil lamps, wood fires etc. The Industrial Revolution forced the proliferation of light sources and the brightness of those sources across the British Isles. Gas lights - never really ubiquitous outside of major urban centres - nonetheless opened up the night to those who had hitherto retreated from it. Once the electric lightbulb, with its powerful luminescence and lower cost, changed the British night from dark to light, the practice of two sleeps quickly faded into obscurity. No more was it necessary to stop work when the sun went below the horizon; no longer was it necessary to fear the night and barricade oneself behind locked doors. In short, people began experiencing the night (for both work and leisure) and sleeping later - to the point where the first sleep became the only sleep. In a very short period of time indeed - perhaps as little as one hundred and fifty years - your ancestors went from a nocturnal pattern of sleep that had endured for millennia whereby we slept and then woke and then slept again, to a consolidated sleep determined primarily by the growth of artificial light. Your ancestors from almost certainly followed the practice of two sleeps. What is perhaps equally important is that, since England was the first country to industrialise, they were also probably the first to abandon the practice. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (Co-Editor of Versus History) @thelibrarian6 Bibliography Ekirch, A. Roger. Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies. (http://www.history.vt.edu/Ekirch/sleep_39_03_715.pdf ) Ekirch, A. Roger. Sleep We Have Lost: Post-industrial Slumber in the British Isles (https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5f7d/10e30df23c62edc499ff26e909764e8946ad.pdf?_ga=2.82364371.494877159.1561369868-1007184158.1561369868) Koslofsky, Craig. Evening's Empire: A History of the Night in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge and New York Cambridge University Press 2011) In short, yes. No matter whether you currently reside in the Americas, Europe, Africa, Australia, or Asia, you are related to royalty. It is a mathematical certainty. You are the product, in a biological and historical sense, of an unbroken line of procreation and survival, dating back in time at least as long as Homo Hominids have existed and, most probably, much, much further back than even that. Your ancestors survived for hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of years, so you could enjoy that pizza and this article. It makes sense that, particularly with the rise of genealogy websites and DNA ancestry services, people around the world are increasingly asking one particular question and, perhaps more importantly, able to have this question answered. The question is this: “Am I related to royalty?”. Regardless of the rationale driving this question - whether it be narcissism or practicality (blue blood might make you feel important and it could be very profitable in terms of inheritance rights), the question is a legitimate one - our current identity is bound so intricately (and often messily) with those who carried our blood through the millennia. We all come from somewhere. Where is that somewhere? There is also a romance to the uncovering of an ancestry either steeped in, or merely anointed by, royal blood: taking part in the achievements of our predecessors - bringing pride or infamy - can become, rightly or wrongly, part of our very own myth-making as individuals. When was the last time you told someone proudly of the achievements of your own children? Imagine if you could tell those same people that you were related to the man who overthrew King Richard III of England or the Iceni Queen who punished the Romans so defiantly. Confirmation of existence? Perhaps. Bragging rights? Most certainly. To get back to the question: “Am I descended from Royalty?”. The popular geneticist, Adam Rutherford, in his many works, including A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, explains the irrefutable mathematics of the situation: there have been ‘only’ about 108 billion Homo sapiens. Taking as his starting point the emergence of what we may call our direct human ancestors (hominids very much like us) 50,000 years ago, Rutherford addresses a common misconception about ancestry: it does not resemble a tree, inasmuch as a tree has separate and distinct branches that extend, in a linear fashion, outwards and away from the trunk. Tree branches may have smaller branches extending outwards from them, but they are always linear - they never rejoin another branch. They exist in isolation from every other branch except the one from which they sprout. This is an impossible scenario, genealogically speaking. As we are all born of two parents*, then for the ‘family tree’ metaphor to be in any way accurate, we would expect every generation that is born to necessarily take itself one branch further away from everybody else (including the original parents and their relatives), genetically and relationally speaking - into isolation. Metaphorically, the branches should only get further and further away from the trunk of the tree, and can only stretch in two directions - backwards and forwards. Some ‘simple’ addition tells us this can’t be true. Take the following as true: You have two parents; your parents each had two parents; their parents each had two parents and so on. Add these together and go back as far as you can. 2+4+8+16+32+64 etc. If you do this and go back a ‘mere’ thousand years, the number you arrive at will be over 1 trillion. That’s 1 trillion people in your direct family tree alone. That number exceeds the sum of all humans that have ever existed - by some way. To extrapolate even further, if there are 8 billion people currently on the planet and they each have 1 trillion people in their own linear family trees, then within the last thousand years there have lived and died more than 8 sextillion humans. That’s 8 followed by 21 zeros. In only the last one thousand years. What if we went back 50,000 years - to the point in time that Rutherford and others see the emergence of Homo sapiens that could be said to correspond, in a behavioural sense, to us today? The mind boggles. And it should. So, what’s happening here and how does this relate to the question in the title? Genealogy should resemble a tangled net rather than a 'neat' tree. You see, the numbers of ancestors that we have increases exponentially as opposed to linearly; it's the difference between calculating 2+4+8+16... as opposed to 1+1+1+1… What this means, and what Rutherford, Mathematicians such as Joseph T. Chang, and Computer Scientists such as Mark Humphrys, understand is that ancestral lineage is not linear at all, it is a complicated mesh of overlapping, shared, repeated, and interconnected relationships. In short, every person on this planet is related, in a genealogical sense, to everybody else. More than this - and this is where things get particularly interesting - we all share common ancestors. Even more than this, we all share the same common ancestor/s! In order that we understand this (and do so in as simple a manner as possible) let’s go back to Africa. The most recent ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis - that all living humans are descended from Homo sapiens who emerged from, and then left, Africa between 200-300,000 years ago - rules out parallel evolution (humans evolving in different geographical locations at the same time). What this means is that, if there is only one geographical and evolutionary source for Homo sapiens, then we must, out of necessity, all be related to that source. One of the first significant elements of the human genome that was sequenced was mitochondrial DNA. Not wanting to get unnecessarily complex, mitochondrial DNA is almost exclusively inherited by children from their mothers. Combine this with the understanding of our geo-evolutionary origin (Africa) then it is an absolute certainty that every living person alive today can trace, through their mitochondrial DNA, their genealogy all the way back to a single female ancestor. We can do something similar with Y-chromosome DNA, which is passed almost unchanged from father to son. And so, in the public imagination we are all descended by an unbroken series of genetic links back to a single woman and a single man: the so-called ‘Mitochondrial Eve’ and ‘Y-Chromosomal Adam’. Mitochondrial DNA can be traced through your female ancesters. Counter-intuitively, these two individuals are unlikely to have been the first humans - they are ‘merely’ the MRCA, or Most Recent Common Ancestor, of all humans alive today. Other humans - probably millions - lived and died without leaving children to contribute to the lineage that would mesh with ours. What is perhaps even more astonishing than this is that, because of the interconnectedness of our species - helped in part by our migrations from village to village, town to town, country to country, and continent to continent - the MRCA of all people living today, probably lived just a few thousand years ago! Now that we have established our messy interconnectedness as Homo sapiens, let’s get back to royalty. Some readers may feel a little cheated by what has just been read above - the rather impersonal and blanket claim that ‘we are all related’. “Where’s the romance in that?”, one might ask. Well, let us get more specific. Using the statistical models of people such as Joseph T. Chang, we can circumvent any feeling that our general genealogical relationship to others is somehow boring, and narrow down our ancestral links to more, let us say, exciting specifics. For example, if we disregard only very recent immigration into Europe, the MRCA of all Europeans is either a man or woman who lived in the very recent past - about 600 years ago. Adam Rutherford goes one step further, demonstrating that almost every single European - and therefore anyone of European descent living in the New World - has royalty in their blood. Specifically, they have the Y-chromosome DNA of Charlemagne - Charles the Great - and/or the mitochondria of four out of his five wives. Charlemagne It is crucial to make note of something - and this is where we depart from statistics and move into history - the number of human beings currently alive that have, to any discoverable degree, documented ancestry, is miniscule. Unless your ancestors enjoyed wealth or significant historical impact, chances are there will be little to no evidence of their existence on this planet. Before the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenburg in the 1440’s, the world’s documentation was handwritten, some of which could be painstaking, most of which would be costly. Until the moveable-type printing press proliferated around the world, the fact of the matter was this: regardless of where around the world you lived and died, unless your life was viewed as worthy of documentation by someone with the means and the inclination to do so, it was likely to be forever ignored by posterity. Occasionally, bureaucracy would fortuitously record the lives of common people. For example, the Domesday Book - commissioned by William the Conqueror after his defeat of Harold of Wessex at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and completed in 1086 - provides historians with a wonderful trove of social history. The ‘Great Survey’ of the people of England and Wales was undertaken for the purposes of taxation - William needed to assert his royal pecuniary rights over the people of his newly conquered lands and, in order to do so, needed to know the levels of wealth and property of all the people occupying these lands. Consequently, though the motive of William of Normandy was to exert his royal control, one important outcome of the Domesday Book was detailed proof of the existence of people who would otherwise have disappeared from the historical record. However, such serendipitous recording of the existence of ‘common people’ was the exception rather than the rule. In most parts of the world, well beyond the invention of the printing press or, indeed, the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the historical record was primarily oral. Unfortunately, oral history often hits the same roadblocks as written history - it mostly records the lives of only those deemed ‘worthy’ of the effort. In a very roundabout way what this means is that, depending on the geographical origins of your antecedents, the socio-economic route by which your ancestors travelled (by and large, an impoverished one), and whether or not they did something worth noting, chances are there is no evidence whatsoever of their existence. Except for you. You are the evidence of their existence. You may be the only evidence. And this brings us back to statistical models…

Since there may be little to no evidence of your genealogical history beyond your most immediate ancestors, we must take refuge in statistics. Ignoring Benjamin Disraeli’s supposed claim that “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics”, in this case the mathematics is irrefutable. If you are of European ancestry you are related to royalty. In fact, if you currently reside in the Americas - including the Caribbean and Bermuda - you are, to a high degree of certainty, related to English royalty specifically: “For example, almost everyone in the New World must be descended from English royalty—even people of predominantly African or Native American ancestry, because of the long history of intermarriage in the Americas. Similarly, everyone of European ancestry must descend from Muhammad.” (Chang) To continue, if you live in North America, whether your ancestors left from Plymouth Harbour on the Mayflower in 1620 or fled from Ireland during the potato famine of the mid nineteenth century, they took with them the DNA of royalty. Whether your ancestors were brutally enslaved and transported to the Americas in chains or were native to the land colonised by Europeans, you are related to royalty - whether it be from the royal houses of England, Europe, Africa, Asia or the Americas. It is a statistical certainty. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (Co-Editor of Versus History) @thelibrarian6 Bibliography: Chang, Joseph T. Recent Common Ancestors of all Present-Day Individuals, (Yale University 1999) http://www.stat.yale.edu/~jtc5/papers/CommonAncestors/AAP_99_CommonAncestors_paper.pdf Olson, S. The Royal We, The Atlantic (May 2002) https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/05/the-royal-we/302497/ 1) Probably the most iconic image of American Independence ever … features loads of British flags in the background!The famous painting entitled ‘Declaration of Independence’ was by the American artist John Trumbull. This image - which featured on the $2 Dollar Bill - was not actually commissioned until 1817, some 41 years after the actual ‘Declaration of Independence’ came into effect. Incidentally, the painting does not depict the ‘declaration’ element of 4 July 1776 at all. Rather, it shows the presentation of the draft document to the Continental Congress for consideration prior to signing. Here is another surprise: if one looks at the wall behind the draftees, a collection of British flags is visible, including the King’s Colours - the forerunner of the Union Jack - the very flag that represented the Monarch (George III) that the signatories were declaring independence from. 2) 8 of the 56 SIGNATORIES were actually born in Britain. 2 were born in England!It might come as something of a surprise to learn that many of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence had actually celebrated their British connections at one time or another prior to renouncing them. George Washington, for instance, had fought for Britain against the French and their Native American allies during the Seven-Years’ War / French and Indian War 1756-1763, donning the famous British Redcoat. However, perhaps even more surprisingly, two of the signatories were actually born in England, with 8 in total being born in the British Isles. Robert Morris, who is considered to be one of the architects of the American financial system, was born 3000 miles away in Liverpool. Moreover, Button Gwinnett, the second signatory of the Declaration of Independence, was born in the quiet village of Down Hatherley in Gloucestershire, in 1735. 3) The Declaration of Independence cites the actions OF THE BRITISH KING as the reason for the political separation.The most well-known part of the Declaration of Independence is the preamble, with the famous line ‘We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness …’ which many will have heard recited or quoted. However, the lesser-known, but crucially important second part of the Declaration of Independence includes a long list of grievances against the British King, which would have been longer still if all of Thomas Jefferson’s original recommendations had been upheld. In the minds of the signatories, the list provides evidence for the separation between America and Britain. In total, eighteen of these begin with the word ‘He’, referring squarely and solely to the supposed ills committed by the British King, George III. These grievances include - but are not limited to - King George III’s refusal to pass necessary laws, stationing a large number of British troops in the colonies, obstructing justice, imposing taxes without consent and cutting off trade. Therefore, much of the content of the American Declaration of Independence is actually focused on the alleged tyrannical actions of the British sovereign.

I hope that you found that interesting and thanks for reading. You can check out our Podcast on the causes of American Independence here. Plus, the Podcast on why Britain lost the war that raged until 1783 here. To finish, here is the Podcast with my quick overview on why King George III deserves a more positive appraisal. Happy July 4 and Independence Day to each and all! Patrick @historychappy Co-Editor Did you know ...The linguistic and cultural exchanges between the British Isles and Germany are nothing new. They have been a key feature of the shared history between the two nations for many, many years. The English language is famous for incorporating words, phrases and inspiration from many others, which is no surprise given her history of prolonged and diverse cultural interactions through the centuries. We at @VersusHistory have already discussed how the English language has absorbed words from Arabic, such as 'Admiral' and 'Loot' from the languages of the Indian Subcontinent. However, how many of these 11 words did you know originated from the German language?!

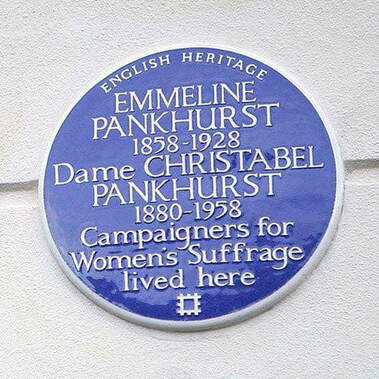

Angst Delicatessen Fest Hamster Hinterland Noodle Poltergeist Prattle Rucksack Spritz Waltz Perhaps there were some surprises amongst the eleven? In any event, it is always interesting to be reminded of the fact that the English language has evolved over the years by incorporating and innovating! Patrick @VersusHistory blue plaques for women! |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed