|

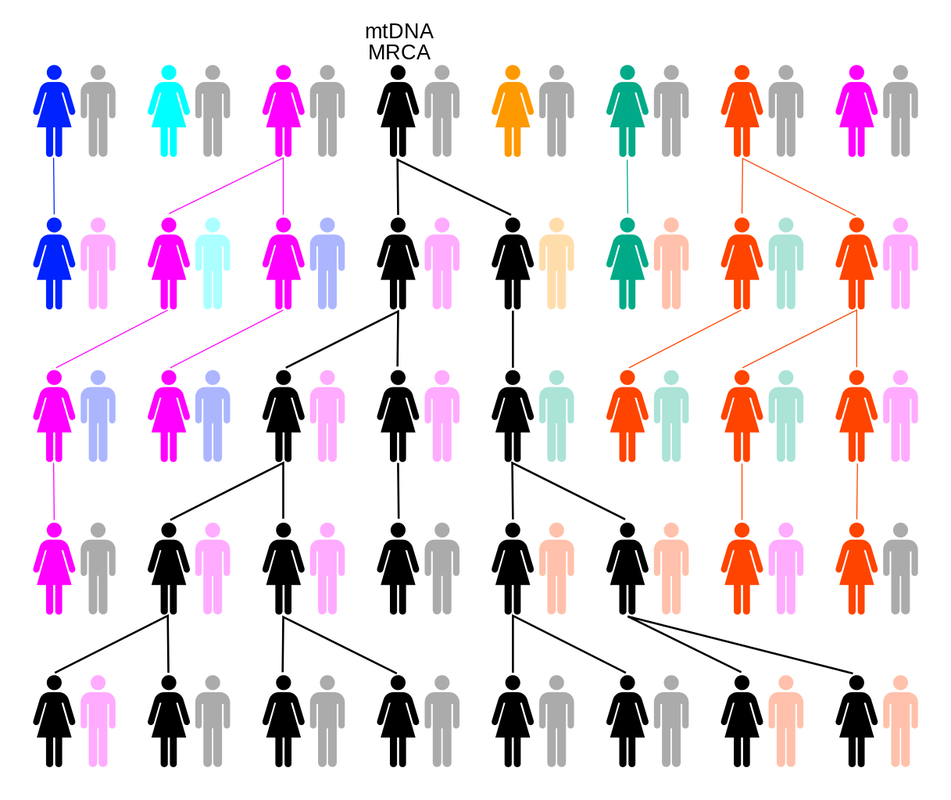

In short, yes. No matter whether you currently reside in the Americas, Europe, Africa, Australia, or Asia, you are related to royalty. It is a mathematical certainty. You are the product, in a biological and historical sense, of an unbroken line of procreation and survival, dating back in time at least as long as Homo Hominids have existed and, most probably, much, much further back than even that. Your ancestors survived for hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of years, so you could enjoy that pizza and this article. It makes sense that, particularly with the rise of genealogy websites and DNA ancestry services, people around the world are increasingly asking one particular question and, perhaps more importantly, able to have this question answered. The question is this: “Am I related to royalty?”. Regardless of the rationale driving this question - whether it be narcissism or practicality (blue blood might make you feel important and it could be very profitable in terms of inheritance rights), the question is a legitimate one - our current identity is bound so intricately (and often messily) with those who carried our blood through the millennia. We all come from somewhere. Where is that somewhere? There is also a romance to the uncovering of an ancestry either steeped in, or merely anointed by, royal blood: taking part in the achievements of our predecessors - bringing pride or infamy - can become, rightly or wrongly, part of our very own myth-making as individuals. When was the last time you told someone proudly of the achievements of your own children? Imagine if you could tell those same people that you were related to the man who overthrew King Richard III of England or the Iceni Queen who punished the Romans so defiantly. Confirmation of existence? Perhaps. Bragging rights? Most certainly. To get back to the question: “Am I descended from Royalty?”. The popular geneticist, Adam Rutherford, in his many works, including A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, explains the irrefutable mathematics of the situation: there have been ‘only’ about 108 billion Homo sapiens. Taking as his starting point the emergence of what we may call our direct human ancestors (hominids very much like us) 50,000 years ago, Rutherford addresses a common misconception about ancestry: it does not resemble a tree, inasmuch as a tree has separate and distinct branches that extend, in a linear fashion, outwards and away from the trunk. Tree branches may have smaller branches extending outwards from them, but they are always linear - they never rejoin another branch. They exist in isolation from every other branch except the one from which they sprout. This is an impossible scenario, genealogically speaking. As we are all born of two parents*, then for the ‘family tree’ metaphor to be in any way accurate, we would expect every generation that is born to necessarily take itself one branch further away from everybody else (including the original parents and their relatives), genetically and relationally speaking - into isolation. Metaphorically, the branches should only get further and further away from the trunk of the tree, and can only stretch in two directions - backwards and forwards. Some ‘simple’ addition tells us this can’t be true. Take the following as true: You have two parents; your parents each had two parents; their parents each had two parents and so on. Add these together and go back as far as you can. 2+4+8+16+32+64 etc. If you do this and go back a ‘mere’ thousand years, the number you arrive at will be over 1 trillion. That’s 1 trillion people in your direct family tree alone. That number exceeds the sum of all humans that have ever existed - by some way. To extrapolate even further, if there are 8 billion people currently on the planet and they each have 1 trillion people in their own linear family trees, then within the last thousand years there have lived and died more than 8 sextillion humans. That’s 8 followed by 21 zeros. In only the last one thousand years. What if we went back 50,000 years - to the point in time that Rutherford and others see the emergence of Homo sapiens that could be said to correspond, in a behavioural sense, to us today? The mind boggles. And it should. So, what’s happening here and how does this relate to the question in the title? Genealogy should resemble a tangled net rather than a 'neat' tree. You see, the numbers of ancestors that we have increases exponentially as opposed to linearly; it's the difference between calculating 2+4+8+16... as opposed to 1+1+1+1… What this means, and what Rutherford, Mathematicians such as Joseph T. Chang, and Computer Scientists such as Mark Humphrys, understand is that ancestral lineage is not linear at all, it is a complicated mesh of overlapping, shared, repeated, and interconnected relationships. In short, every person on this planet is related, in a genealogical sense, to everybody else. More than this - and this is where things get particularly interesting - we all share common ancestors. Even more than this, we all share the same common ancestor/s! In order that we understand this (and do so in as simple a manner as possible) let’s go back to Africa. The most recent ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis - that all living humans are descended from Homo sapiens who emerged from, and then left, Africa between 200-300,000 years ago - rules out parallel evolution (humans evolving in different geographical locations at the same time). What this means is that, if there is only one geographical and evolutionary source for Homo sapiens, then we must, out of necessity, all be related to that source. One of the first significant elements of the human genome that was sequenced was mitochondrial DNA. Not wanting to get unnecessarily complex, mitochondrial DNA is almost exclusively inherited by children from their mothers. Combine this with the understanding of our geo-evolutionary origin (Africa) then it is an absolute certainty that every living person alive today can trace, through their mitochondrial DNA, their genealogy all the way back to a single female ancestor. We can do something similar with Y-chromosome DNA, which is passed almost unchanged from father to son. And so, in the public imagination we are all descended by an unbroken series of genetic links back to a single woman and a single man: the so-called ‘Mitochondrial Eve’ and ‘Y-Chromosomal Adam’. Mitochondrial DNA can be traced through your female ancesters. Counter-intuitively, these two individuals are unlikely to have been the first humans - they are ‘merely’ the MRCA, or Most Recent Common Ancestor, of all humans alive today. Other humans - probably millions - lived and died without leaving children to contribute to the lineage that would mesh with ours. What is perhaps even more astonishing than this is that, because of the interconnectedness of our species - helped in part by our migrations from village to village, town to town, country to country, and continent to continent - the MRCA of all people living today, probably lived just a few thousand years ago! Now that we have established our messy interconnectedness as Homo sapiens, let’s get back to royalty. Some readers may feel a little cheated by what has just been read above - the rather impersonal and blanket claim that ‘we are all related’. “Where’s the romance in that?”, one might ask. Well, let us get more specific. Using the statistical models of people such as Joseph T. Chang, we can circumvent any feeling that our general genealogical relationship to others is somehow boring, and narrow down our ancestral links to more, let us say, exciting specifics. For example, if we disregard only very recent immigration into Europe, the MRCA of all Europeans is either a man or woman who lived in the very recent past - about 600 years ago. Adam Rutherford goes one step further, demonstrating that almost every single European - and therefore anyone of European descent living in the New World - has royalty in their blood. Specifically, they have the Y-chromosome DNA of Charlemagne - Charles the Great - and/or the mitochondria of four out of his five wives. Charlemagne It is crucial to make note of something - and this is where we depart from statistics and move into history - the number of human beings currently alive that have, to any discoverable degree, documented ancestry, is miniscule. Unless your ancestors enjoyed wealth or significant historical impact, chances are there will be little to no evidence of their existence on this planet. Before the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenburg in the 1440’s, the world’s documentation was handwritten, some of which could be painstaking, most of which would be costly. Until the moveable-type printing press proliferated around the world, the fact of the matter was this: regardless of where around the world you lived and died, unless your life was viewed as worthy of documentation by someone with the means and the inclination to do so, it was likely to be forever ignored by posterity. Occasionally, bureaucracy would fortuitously record the lives of common people. For example, the Domesday Book - commissioned by William the Conqueror after his defeat of Harold of Wessex at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and completed in 1086 - provides historians with a wonderful trove of social history. The ‘Great Survey’ of the people of England and Wales was undertaken for the purposes of taxation - William needed to assert his royal pecuniary rights over the people of his newly conquered lands and, in order to do so, needed to know the levels of wealth and property of all the people occupying these lands. Consequently, though the motive of William of Normandy was to exert his royal control, one important outcome of the Domesday Book was detailed proof of the existence of people who would otherwise have disappeared from the historical record. However, such serendipitous recording of the existence of ‘common people’ was the exception rather than the rule. In most parts of the world, well beyond the invention of the printing press or, indeed, the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the historical record was primarily oral. Unfortunately, oral history often hits the same roadblocks as written history - it mostly records the lives of only those deemed ‘worthy’ of the effort. In a very roundabout way what this means is that, depending on the geographical origins of your antecedents, the socio-economic route by which your ancestors travelled (by and large, an impoverished one), and whether or not they did something worth noting, chances are there is no evidence whatsoever of their existence. Except for you. You are the evidence of their existence. You may be the only evidence. And this brings us back to statistical models…

Since there may be little to no evidence of your genealogical history beyond your most immediate ancestors, we must take refuge in statistics. Ignoring Benjamin Disraeli’s supposed claim that “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics”, in this case the mathematics is irrefutable. If you are of European ancestry you are related to royalty. In fact, if you currently reside in the Americas - including the Caribbean and Bermuda - you are, to a high degree of certainty, related to English royalty specifically: “For example, almost everyone in the New World must be descended from English royalty—even people of predominantly African or Native American ancestry, because of the long history of intermarriage in the Americas. Similarly, everyone of European ancestry must descend from Muhammad.” (Chang) To continue, if you live in North America, whether your ancestors left from Plymouth Harbour on the Mayflower in 1620 or fled from Ireland during the potato famine of the mid nineteenth century, they took with them the DNA of royalty. Whether your ancestors were brutally enslaved and transported to the Americas in chains or were native to the land colonised by Europeans, you are related to royalty - whether it be from the royal houses of England, Europe, Africa, Asia or the Americas. It is a statistical certainty. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (Co-Editor of Versus History) @thelibrarian6 Bibliography: Chang, Joseph T. Recent Common Ancestors of all Present-Day Individuals, (Yale University 1999) http://www.stat.yale.edu/~jtc5/papers/CommonAncestors/AAP_99_CommonAncestors_paper.pdf Olson, S. The Royal We, The Atlantic (May 2002) https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/05/the-royal-we/302497/

0 Comments

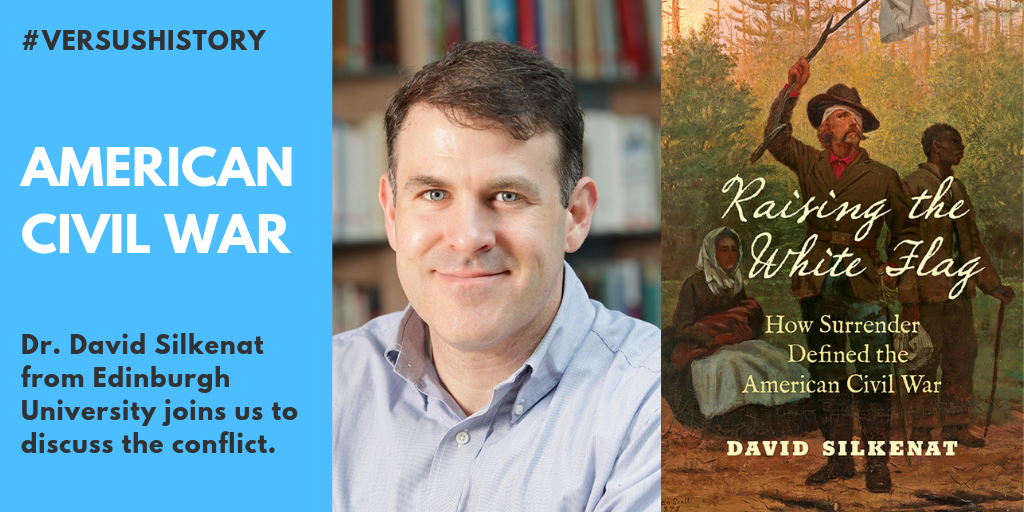

Dr, David Silkenat joined the Versus History Podcast for Episode #80 to discuss the American Civil War. To celebrate, we would like to give away a gratis copy of David's new book, 'Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War', published by The University of North Carolina Press, to one lucky listener of the Podcast. The Amazon page for the book can be found here. The question itself was revealed by Dr Silkenat on the Podcast itself, so all you need to do is download it here and listen! Good luck! |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed