|

Win a copy of The new SAS epic from bestselling military historian Damien Lewis! The author joined the Versus History Podcast on Episode #106 to answer a broad range of questions about his book. We would love to give away a copy to one of our lucky listeners! To be in with a chance of winning Damien's brand new book, just answer the question below correctly! The competition closes on Thursday 10 December 2020.

0 Comments

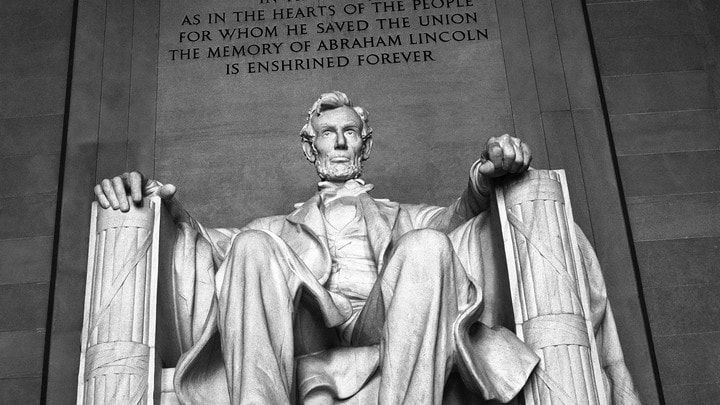

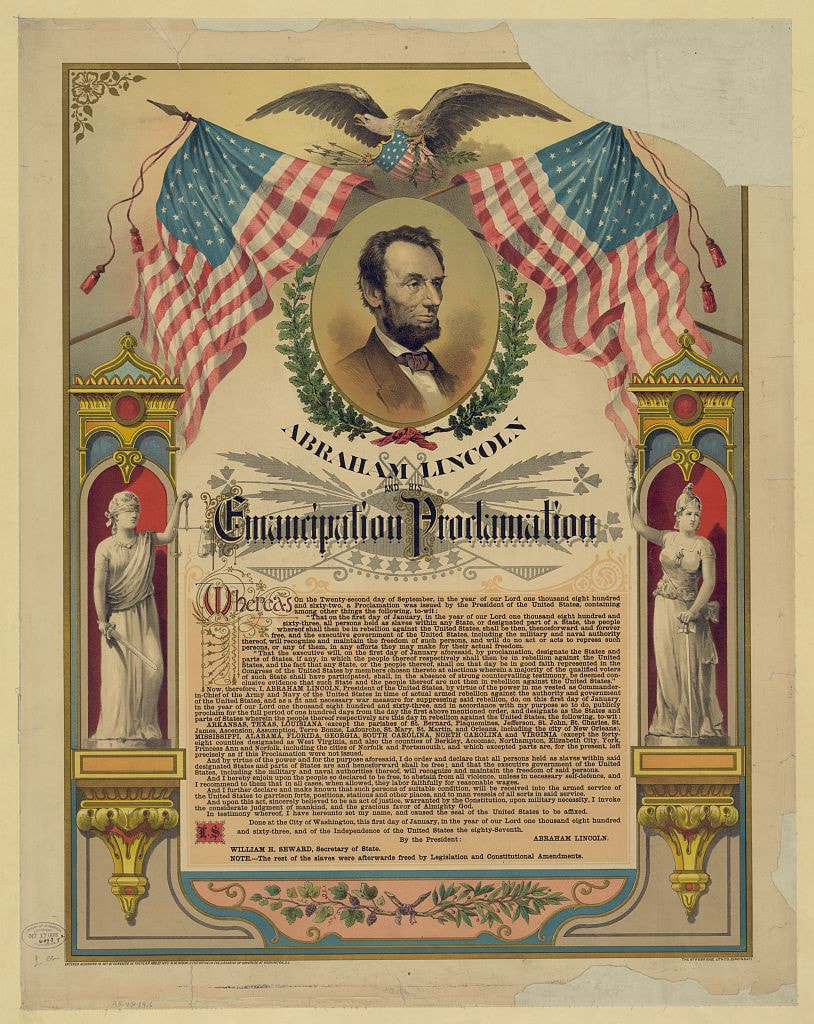

So I got an Abraham Lincoln facemask. I got it for school. To get into the spirit of return to school life. An inspiring person. Provoke conversation with students, maybe staff too. And maybe while out in shops, getting a knowing nod from others in the history community. No one batted an eyelid. No one in school mentioned it other than to say it freaked them out. So yes, I am a fan of Old Abe. I’m drawn to those who defy odds and reach greatness with their drive and intelligence rather than money or privilege. And then once in high office, it is their skill that seems to save the day. (My Twitter name @tacicero78 may give a clue to another hero of mine.) That Lincoln is so relevant is no surprise. The issues he wrestled with plague American society today. Although slavery was officially outlawed in the US, the worldwide inability to end racism are becoming more and more apparent, both historically and in modern life. Still so many see Lincoln as an enigma. So many new books (and blogs, and my upcoming podcast for the HA) on the man still search for the real Lincoln. But here’s the thing. Lincoln is one of the most straight forward political figures in history. Yes, he was a politician, so there are lots of times when Lincoln played politics rather than give a true opinion on a matter. Yes, a lot of the sources we have on Lincoln were written after his assassination so have an air of fallen hero worship. The overall reason people think Lincoln is an enigma is the baggage we bring to him in the 21st Century rather than what he presents. To us today the subject of slavery is an easy one. It was evil. A pervasive evil that dehumanised those who were enslaved and rotted the society it was meant to serve. It is this baggage that we must be aware of when looking at this time period. For while there were some (too few) in the time of Lincoln who would agree with us, there were too many who saw slavery as a question attached to a political spectrum. Most of that spectrum would sicken us today. In Lincoln’s time, slavery was a political question for most, a moral question for some. And the spectrum was wide-ranging. There were the moral abolitionists such as the moral terrorist John Brown whose actions spurred the south to form an army. William Lloyd Garrison who campaigned for abolition from his newspaper The Liberator. Some were against slavery’s spread to the newly conquered western lands. (Within this was often a racist element – as they did not want black people in the west, slave or free) There were those who wanted an end to slavery but could not constitutionally see a way forward (Here sits Lincoln). There were those with no opinion. Those who gained from it, be it in the north or the south. Like New York, who prospered from the trade in goods made by enslaved people. Those who saw it as a religious right to practice slavery and those who justified it based on bad science. Within this spectrum sat Lincoln who was always, consistently against slavery. Never once is he recorded as saying that he supports it. I’ll let him sum it up in a letter he sent a Kentuckian Albert Hodges. He was very good with words. I am naturally anti-slavery. If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong. I cannot remember when I did not so think, and feel. Despite this clear statement, which can be backed up with many other quotes and examples, Lincoln was not an abolitionist. He would sooner have seen slavery die a slow death or to be euthanized by the law of the land. How can this be? If he is against slavery then surely he has to be an abolitionist. Well, no. Remember we have to leave our views for a while, as right and noble as they are. Lincoln thought of himself as a constitutionalist, even when acting outside of it. (If he were here today, his facemask would have been a copy of the Declaration of Independence or the Bill of Rights) In the same letter, he set out his predicament. ‘And yet I have never understood that the Presidency conferred upon me an unrestricted right to act officially upon this judgement and feeling.’ Even so, it was Lincoln that finally freed the enslaved on a massive scale. Those who look for a ‘yeah but . . .’to my ‘Lincoln was the greatest president because . . .’ turn to a letter Lincoln wrote to newspaper editor Horace Greely in 1862. In that letter, they turn to one section which proves Lincoln’s ambivalence towards slavery. My paramount objection in this struggle is to save the Union and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do that. Yes, I know. Hardly Gettysburg address is it? A little context may help. Lincoln’s was responding to a letter Greely published in his newspaper admonishing Lincoln for not acting quickly enough on slavery. Lincoln answered this public letter with his own rather sniffy reply. And yes to our modern ears it sounds at best flat, at worst abandoning. But perhaps on the same desk, he wrote this he had drafted the Emancipation Proclamation. I know that it had a dubious legal basis. Borne out of military tactics no one was actually freed and it did not apply to slave states still loyal to the Union. The language was perfunctory rather than inspiring (although I quite like, ‘shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.) From then on though (or should I say, then, thenceforward and forever) it changed the dynamics of the war. It gave hope to millions that would one day bear fruit. The passage of the 13th Amendment was unusual for many reasons. It would finally place the word ‘slavery’ in the Constitution. It was debated and voted upon when those who it would affect the most did not consider themselves part of the same country anymore. It had the president’s hand all over it in a time when it was not a president’s role to be the chief legislator. There were opportunities for Lincoln to reconcile with the South and set in motion steps that would end federal involvement in slavery, therefore protecting it for generations. There were times when Lincoln could have sided with the south to fight a foreign power, uniting the country against a foe that would stir nationalistic pride and divert attention away from slavery. He did none of those things. While pressing for the successful end to the civil war he pressed for the end of slavery in ways that even he thought stretched his powers. And he did it because he was as he had always been against slavery. However, Lincoln was able to hold two separate views. One on slavery, which he saw as wrong and worked to abolish. Another on race. This is more complicated. I won’t hide behind, ‘he was a man of his times’. And I don’t need to quote him on the many times he sees the races as separate. He proved it in his actions. He advocated and worked for the emigration of black people out of the United States to Central America and to Africa. He set money aside for this and met with groups of black leaders hoping to persuade then to drum up support. They were less enthusiastic than he. The colonisation plan was so poorly thought out that the only one undertaken during Lincoln’s presidency was a disaster. Yet Lincoln sees this as the only option. Once emancipated he does not see black people as able to remain in the US. What was he thinking? Once in another country, what would their nationality be? Would they be an American colony? Would they be US citizens? Able to return? Would they have paid taxes back to the USA? Could they have voted? Or were they simply to be abandoned and forgotten about. The colonisation project never took off. Once the Emancipation Proclamation was issued Lincoln became less vocal about it. In that time he realised that black Americans loved the US and were willing to fight and die in huge numbers to save the Republic. They rightly wanted to remain and enjoy freedom and the benefits that citizenship entails. He was schooled by the best in his meetings with Frederick Douglass that black people were intelligent, passionate and able to hold him to account. In this Lincoln did grow. His views changed. How much he would continue to change we will never know. In his last speech from a window on the White House, Lincoln said he was in favour of suffrage for those who had aided the Union. This was a huge step forward. For a sitting president to simply say this was progress. It shows progress for Lincoln as a person. But we can only take this so far. So, what to do with that facemask. Lincoln was the person who freed slaves in huge numbers. (Let’s not forget self-emancipation and assistance of the Underground Railroads) For that Lincoln will always be the greatest president of the United States. In other views, he was less admirable. Sure a man of his times. And in the context of his times, lightyears ahead of others. He was getting better. He was learning. And I admire that skill in a leader. I can’t think of too many leaders who grow that much when in power. But I won’t wear the mask again. I’ll keep his picture up in my classroom with his quote underneath that all are created equal. I will keep learning about Lincoln. And maybe in learning about Lincoln I have learnt something about history – we search through time, looking for heroes.

Lincoln was a fan of Shakespeare. He would know this from Malvolio in Twelfth Night - Some are born great, some achieve greatness and some have greatness thrust upon them. Lincoln was not born great. He worked with the talents he had to achieve greatness, which he did, more than any other to occupy the same office. And in doing so generations have thrust greatness upon him where maybe it was never needed. By Versus History Guest Blogger Terence Graham (@tacicero78) References The Fiery Trial and Free Soil, Free Labour, Free Men by Eric Foner Lincoln Looks West edited by Richard Etulian Biographies of Lincoln by Michael Burlingame and Doris Kearns Goodwin http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/hodges.htm http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/greeley.htm |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed