|

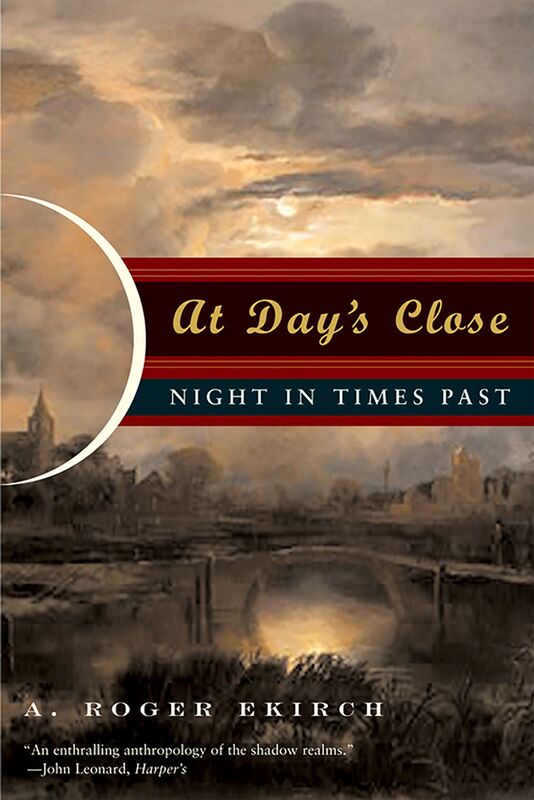

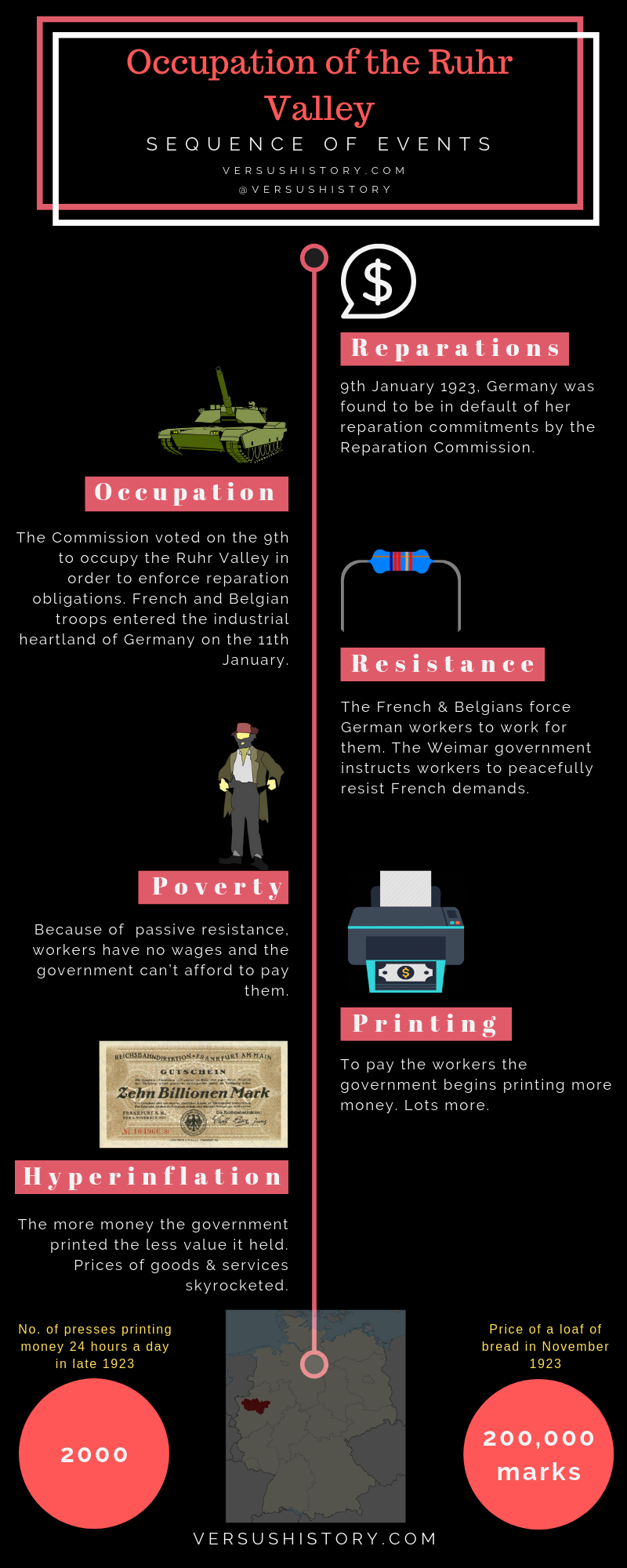

If you are waking up right now, chances are you have had, what clinicians term, one period of consolidated sleep. That is, you went to bed yesterday evening and awoke the following day - this morning. In most parts of the world - particularly the industrialised world - consolidated sleep is the norm. By and large, our patterns of sleep and wakefulness (known as our circadian rhythm) are governed by two things: the cycle of nighttime and daytime; the daily demands on our time. The former is mandated by the movements of the planets (not much we can do about that), the latter is determined by a multitude of factors, perhaps the most significant being the daily work that we have to do. In a sense, for the vast majority of people, we don’t have much control over this either. The Industrial Revolution and state-sponsored education have tended to organise the daily routines of most people around the world, meaning that - exceptions notwithstanding - we carry out our ‘work’ during one continuous block during the day and sleep in one continuous block at night (if we are lucky). It was not always the case. In fact, until relatively recently your ancestors would most probably have maintained a bi-modal sleeping pattern. They had two sleeps a night. In At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, Roger Ekirch’s revelatory investigation into the social history of what people around the world do at night, a rich and varied trove of evidence from across the centuries and the globe, suggested that we had a ‘first sleep’ and then a ‘second sleep’. The first sleep began a couple of hours after the sun went down and lasted for 3-4 hours. After an hour or so of wakefulness (more on this in a moment), people went back to sleep for another 3-4 hours. During this period of wakefulness between the first and second sleeps, evidence abounds that people did either what was necessary - chopped wood, prepared food, prayed and such - or what was enjoyable - read, talked with bedfellows, had sex and so on. According to Ekirch, the surprising point in his discoveries is not that this practice seems to have been almost entirely forgotten in the post-industrialised world, but that it was such a commonality - references abounding in plain sight - in the first place. In England, prior to, and even during, the early phases of the Industrial Revolution, records of first and second sleeps are abundant and exist without any attention being drawn to their being in any way unusual. That’s because, according to Ekirch, they weren’t. In 1840, Charles Dickens dropped a ‘casual’ mention into Barnaby Rudge, “He knew this, even in the horror with which he started from his first sleep, and threw up the window…” Ekirch opens his 2001 paper, Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles, (out of which his book, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past was developed), with journal notes made by the Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson. These notes, written about his time spent camping and hiking through the Cévennes in France in 1878, describe with great poetry what he calls “the stirring hour” and “...this nightly resurrection” - that interval between sleeps which, even by Stevenson’s time, was largely a thing forgotten to history. It is a poignant opening to a piece of research that ‘rediscovered’ a practice which, to your ancestors, would almost certainly have been the norm. Robert Louis Stevenson takes his 'first sleep' in Cevannes WHY did we sleep twice? There have been suggestions that bi-phasal sleep became lodged in western Europe because of the requirements of early Christianity - monkish orders rising during the darkened hours to recite verses and pray - and that this embedded itself in European Catholicism which, in turn, promoted the same such nightly devotions from all strata of society. According to Ekirch, this can’t be the root of segmented sleep, because the very practice not only predates early Christianity, it existed across the world in areas which were, until relatively recently, untouched by Christian missionaries and religious conquistadors. Just why we took two sleeps at night is a complex question, linked perhaps to the dangers our ancestors (and not even to distant ones at that) faced by sleeping through the night - from predators to criminals. Night could be, it must be remembered, a terrifying time for all, dense as it might have been with frightful superstitions, religious paranoia, and the very real criminals that moved unseen. The night time was literally and metaphorically a time when the disreputable elements of life emerged: “Associations with night before the 17th Century were not good," he says. The night was a place populated by people of disrepute - criminals, prostitutes and drunks.” (Kolovsky, Craig.) Breaking sleep, as unnatural as it may seem to us now, could be fundamental to the survival of our ancestors. Sleep was a much more vulnerable state for our ancestors to have to endure than for most of us today. Unless the moon was visible at night, the darkness of the pre-industrial world would have been absolute. When people actually took to their beds for their first sleep was, in part, also related to the darkness because, as Professor Ekirch plainly stated in Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies:

“As in many preindustrial cultures, sleep onset depended less on a fixed timetable than on the existence of things to do.” Since pre industrial England relied so heavily on the daylight to accomplish these ‘things to do’ - our daily toils - once the night arrived it would have been near-impossible to conduct anything except the least arduous of tasks, such as talking, eating, or sleeping. If the work had been accomplished for the day - in the hours of light during which it was possible to accomplish it - then the timing of the ‘first sleep’ need not have been rigid. However, it cannot be overstated just how utterly devoid of light the night could become in a world before the Industrial Revolution. Unless the moon rendered otherwise, darkness would have been near absolute for anyone who could not afford artificial light - candles, oil lamps and such. And this is where the answer to the question of why we no longer have two sleeps at night is to be found: artificial light. Perhaps the more important question isn’t really why we used to have two sleeps and a ‘break’ but why we stopped the practice. The wealthier classes were perhaps the first to move away from the prehistoric ‘two sleep’ pattern because of their earlier access to artificial light - candles, oil lamps, wood fires etc. The Industrial Revolution forced the proliferation of light sources and the brightness of those sources across the British Isles. Gas lights - never really ubiquitous outside of major urban centres - nonetheless opened up the night to those who had hitherto retreated from it. Once the electric lightbulb, with its powerful luminescence and lower cost, changed the British night from dark to light, the practice of two sleeps quickly faded into obscurity. No more was it necessary to stop work when the sun went below the horizon; no longer was it necessary to fear the night and barricade oneself behind locked doors. In short, people began experiencing the night (for both work and leisure) and sleeping later - to the point where the first sleep became the only sleep. In a very short period of time indeed - perhaps as little as one hundred and fifty years - your ancestors went from a nocturnal pattern of sleep that had endured for millennia whereby we slept and then woke and then slept again, to a consolidated sleep determined primarily by the growth of artificial light. Your ancestors from almost certainly followed the practice of two sleeps. What is perhaps equally important is that, since England was the first country to industrialise, they were also probably the first to abandon the practice. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (Co-Editor of Versus History) @thelibrarian6 Bibliography Ekirch, A. Roger. Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies. (http://www.history.vt.edu/Ekirch/sleep_39_03_715.pdf ) Ekirch, A. Roger. Sleep We Have Lost: Post-industrial Slumber in the British Isles (https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5f7d/10e30df23c62edc499ff26e909764e8946ad.pdf?_ga=2.82364371.494877159.1561369868-1007184158.1561369868) Koslofsky, Craig. Evening's Empire: A History of the Night in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge and New York Cambridge University Press 2011)

0 Comments

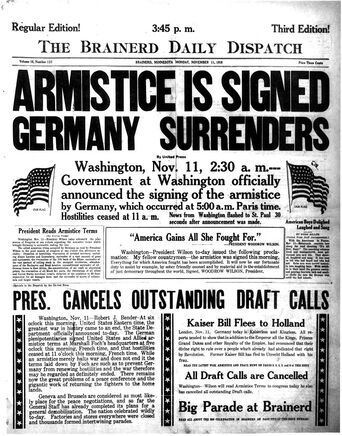

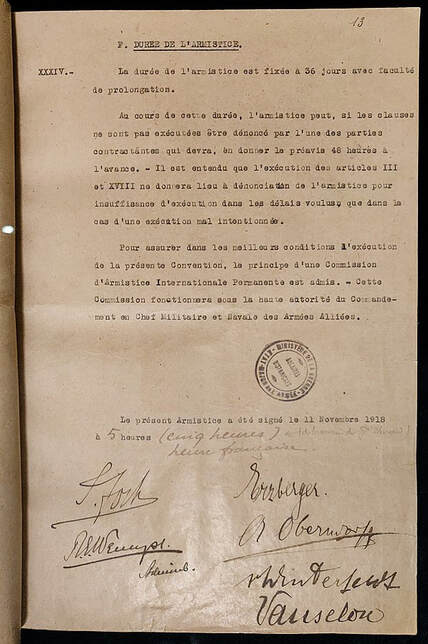

...THAT THE ARMISTICE ENDING WORLD WAR ONE WAS NOT SIGNED AT 11aM (and was written only in French)Every year on the 11th November at 11am, silence falls across many parts of the world as the people of the present remember the sacrifices made in the line of duty by people of the past. Remembrance Day (or Veterans Day in the US) emerged out of an Armistice Day tradition begun by King George V in 1919 while hosting the President of France, Émile Loubet, at Buckingham Palace. The Armistice that King George was celebrating was that which was signed the previous year on the 11th November, 1918 and which signalled the end to hostilities on the Western Front. What is well known is this: we choose to signal the start of remembrance and reflection at 11am every year on the 11th November. There are different traditions and norms, but usually the signal is followed immediately by a minute or more of silence. What is slightly less known is that the timing of 11am should, technically, be observed by the French clock. What is, perhaps, even less well known is that the 11am ‘signal’ for remembrance was chosen not because the Armistice was signed at 11am on 11th November, 1918 - it was no such thing - but because that is when the Armistice came into ‘effect’. The Armistice that helped draw fighting on the Western Front to a close was signed nearly six hours earlier, in a railway carriage deep in the Forest of Compiègne`, approximately 60km north of Paris. In his 1996 book, Armistice 1918, the rather appropriately named Bullitt Lowry explained how on the 6th November 1918, members of the German High Command sent a late night radio message asking for permission from the Allies to send a delegation through the front lines to sue for peace. The man to whom this message was directed was Frenchman, Marshal Ferdinand Foch - the Supreme Allied Commander on the Western Front. According to Lowry, a delegation from Germany crossed No-Man’s Land in three cars, as one German soldier waved a white flag and another sounded a bugle - both indicating a temporary truce that would allow for their unmolested transit. Once they were safely across, the delegation switched cars - to ones of French heritage - and then boarded a train. The train would take them through the night to the Forest of Compiègne - where they would arrive on the morning of November 8th. Awaiting them in a railway siding was the carriage of Foch. It was in this carriage that, over the next four days, the fate of Europe would be decided. Foch is second from the right. He stands next to his carriage - the carriage in which the Armistice was signed. Regardless of the nature and contents of the Armistice that was eventually agreed to by this German delegation, it was, ultimately, signed at just after 5am (some put it as late as 5.45am) on the 11th November. At 6.01am on that same morning, a directive from Marshall Foch was broadcast on Official Radio from Paris which stipulated the following:

The last page of the Armistice document (Emeric84 [CC0]) Henry Nicholas John Gunther was, according to most accounts, the last soldier killed during World War One. An American soldier desperately looking to regain a rank he had recently lost*, Gunther ran headfirst into a hail of German machine-gun fire at 10.59am. Even the German soldiers at which Gunther was running and firing, cognisant of the fact that the war had only one minute left to run, tried to wave the American soldier away. The last soldier to be killed: Henry Nicholas John Gunther. (User:Concord [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)]) And so, when we commemorate the fallen at 11am, remember that the Armistice was signed as the sun rose above a beautiful forest in northern France, but also that the soldiers on the front lines who had to fight on that final morning, knew full well that the war was over for them - provided that they could avoid death until the clocks of Paris struck 11am.

Elliott L. Watson @thelibrarian6 *A letter that Gunther sent home to the US contained criticisms of the conditions on the front. It was intercepted and he was demoted from Sergeant to Private. ...Most of the time no one died in a gladiator fightIf you were to watch Hollywood you would be left with the impression that every gladiator fight ended in the death of the loser. We’ve all seen it. The triumphant gladiator looms over his vanquished foe and waits for the decision of the Emperor. Listening to the crowd, the Emperor pauses before dramatically putting his thumb down, at which the victor finishes off his opponent to the roar of the crowd. Without even going into the questionable thumbs down gesture, the overriding problem with this is that actually only a small proportion of gladiator fights ended in death. It is true that the fate of the defeated was left to the ambitious politician who put on the games, but, as with all entertainment today, it was also a business; gladiators were quite an investment. Gladiators were far from amateurs. Training a good quality fighter could take years of training, feeding and clothing them from their owners, not to mention the time and fights required to gain a reputation. Therefore, summarily executing them meant an instantaneous wiping out of this investment; as such the gladiator’s trainer would often receive compensation from the show’s sponsor were they to be killed. Naturally this is not to say that gladiator fights were not a dangerous business. Death could come either in the course of the fight or as a result of the patron's decision. However, Professor Mary Beard in her book Pompeii: the life of a Roman Town puts the chances of a bout resulting in a death, by either route, somewhere around 13%. Such a rate means that a gladiator's life expectancy was rather short, with the average age of those recorded with tombstones being in their late twenties. However, the fact remains, most of the time that Hollywood scene has it wrong. The vanquished gladiator was far more likely to be spared than skewered.

Conal Smith @prohistoricman ...the black death was actually a good thingIf you know anything about the Black Death, it is most likely that it was a horrible disease that killed huge numbers of people right across Europe a long time ago. This is certainly true, but did you know that (so long as you escaped the illness) it actually hugely improved life for most people in Britain? In the year 1348 a terrible condition began to strike people in England and rampaged through the nation for the next four years. A contemporary description by Giovanni Boccaccio gives us a graphic view of the horrors of the disease which “began both in men and women with certain swellings in the groin or under the armpit. They grew to the size of a small apple or an egg, more or less, and were vulgarly called tumours. In a short space of time these tumours spread from the two parts named all over the body. Soon after this the symptoms changed and black or purple spots appeared on the arms or thighs or any other part of the body, sometimes a few large ones, sometimes many little ones. These spots were a certain sign of death, just as the original tumour had been and still remained” To catch the disease was clearly extremely painful and unpleasant, but also fatal in most cases. Estimates of the casualty rate in England range from one third of the population to roughly half. On a national level it was a disaster. This was perhaps most obvious for those who caught the disease. However, with such a high mortality rate everybody would have close family and friends struck down and been affected in the most harrowing way. Yet, the survivors of the disease actually found their lives materially improved in the second half of the fourteenth century. With such a high proportion of the population removed, and therefore the available pool of labour shrunk radically, peasants, as the majority of the population were, found themselves in demand. Statistical data is inevitably patchy, but the laws passed by the government in the wake of the Black Death reveal the increased value in peasants’ labour.

The Ordinance of Labourers, a law of 1349, stated that when hiring workers “no man pay, or promise to pay, any servant any more wages, liveries, meed, or salary than was wont, as afore” (before the plague) As well as attempting to freeze wages the Ordinance also placed a price freeze on staple foodstuffs such as meat, fish and bread as well as the price that could be charged by skilled craftsmen such as smiths. Fortunately for the labourers of England, evidence suggests this law was unsuccessful. It was followed up by another legal attempt to restrain prices in 1351 called the Statute of Labourers, but neither of these seem to have had a large impact; as many economists will tell you, market forces can be hard to control. In his seminal work Making a Living in the Middle Ages, Chris Dyer states that “the rise in wages was at first modest, and striking improvement often came in the last quarter of the fourteenth century”. So there it is. If you were an agricultural labourer, as most Englishmen were, and you survived the Black Death, you could gain a little more coin for your hard labours and perhaps find it a little easier to put food on the table for yourself and your family. New Book Release: |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed