|

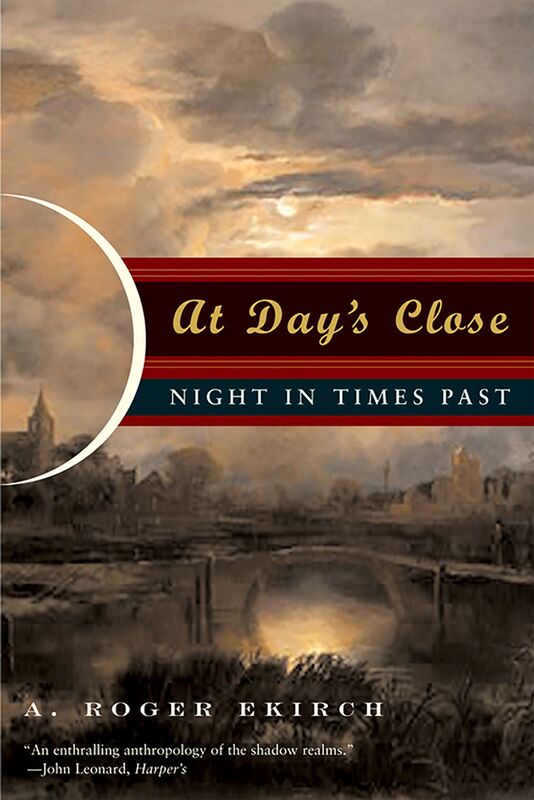

If you are waking up right now, chances are you have had, what clinicians term, one period of consolidated sleep. That is, you went to bed yesterday evening and awoke the following day - this morning. In most parts of the world - particularly the industrialised world - consolidated sleep is the norm. By and large, our patterns of sleep and wakefulness (known as our circadian rhythm) are governed by two things: the cycle of nighttime and daytime; the daily demands on our time. The former is mandated by the movements of the planets (not much we can do about that), the latter is determined by a multitude of factors, perhaps the most significant being the daily work that we have to do. In a sense, for the vast majority of people, we don’t have much control over this either. The Industrial Revolution and state-sponsored education have tended to organise the daily routines of most people around the world, meaning that - exceptions notwithstanding - we carry out our ‘work’ during one continuous block during the day and sleep in one continuous block at night (if we are lucky). It was not always the case. In fact, until relatively recently your ancestors would most probably have maintained a bi-modal sleeping pattern. They had two sleeps a night. In At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, Roger Ekirch’s revelatory investigation into the social history of what people around the world do at night, a rich and varied trove of evidence from across the centuries and the globe, suggested that we had a ‘first sleep’ and then a ‘second sleep’. The first sleep began a couple of hours after the sun went down and lasted for 3-4 hours. After an hour or so of wakefulness (more on this in a moment), people went back to sleep for another 3-4 hours. During this period of wakefulness between the first and second sleeps, evidence abounds that people did either what was necessary - chopped wood, prepared food, prayed and such - or what was enjoyable - read, talked with bedfellows, had sex and so on. According to Ekirch, the surprising point in his discoveries is not that this practice seems to have been almost entirely forgotten in the post-industrialised world, but that it was such a commonality - references abounding in plain sight - in the first place. In England, prior to, and even during, the early phases of the Industrial Revolution, records of first and second sleeps are abundant and exist without any attention being drawn to their being in any way unusual. That’s because, according to Ekirch, they weren’t. In 1840, Charles Dickens dropped a ‘casual’ mention into Barnaby Rudge, “He knew this, even in the horror with which he started from his first sleep, and threw up the window…” Ekirch opens his 2001 paper, Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles, (out of which his book, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past was developed), with journal notes made by the Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson. These notes, written about his time spent camping and hiking through the Cévennes in France in 1878, describe with great poetry what he calls “the stirring hour” and “...this nightly resurrection” - that interval between sleeps which, even by Stevenson’s time, was largely a thing forgotten to history. It is a poignant opening to a piece of research that ‘rediscovered’ a practice which, to your ancestors, would almost certainly have been the norm. Robert Louis Stevenson takes his 'first sleep' in Cevannes WHY did we sleep twice? There have been suggestions that bi-phasal sleep became lodged in western Europe because of the requirements of early Christianity - monkish orders rising during the darkened hours to recite verses and pray - and that this embedded itself in European Catholicism which, in turn, promoted the same such nightly devotions from all strata of society. According to Ekirch, this can’t be the root of segmented sleep, because the very practice not only predates early Christianity, it existed across the world in areas which were, until relatively recently, untouched by Christian missionaries and religious conquistadors. Just why we took two sleeps at night is a complex question, linked perhaps to the dangers our ancestors (and not even to distant ones at that) faced by sleeping through the night - from predators to criminals. Night could be, it must be remembered, a terrifying time for all, dense as it might have been with frightful superstitions, religious paranoia, and the very real criminals that moved unseen. The night time was literally and metaphorically a time when the disreputable elements of life emerged: “Associations with night before the 17th Century were not good," he says. The night was a place populated by people of disrepute - criminals, prostitutes and drunks.” (Kolovsky, Craig.) Breaking sleep, as unnatural as it may seem to us now, could be fundamental to the survival of our ancestors. Sleep was a much more vulnerable state for our ancestors to have to endure than for most of us today. Unless the moon was visible at night, the darkness of the pre-industrial world would have been absolute. When people actually took to their beds for their first sleep was, in part, also related to the darkness because, as Professor Ekirch plainly stated in Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies:

“As in many preindustrial cultures, sleep onset depended less on a fixed timetable than on the existence of things to do.” Since pre industrial England relied so heavily on the daylight to accomplish these ‘things to do’ - our daily toils - once the night arrived it would have been near-impossible to conduct anything except the least arduous of tasks, such as talking, eating, or sleeping. If the work had been accomplished for the day - in the hours of light during which it was possible to accomplish it - then the timing of the ‘first sleep’ need not have been rigid. However, it cannot be overstated just how utterly devoid of light the night could become in a world before the Industrial Revolution. Unless the moon rendered otherwise, darkness would have been near absolute for anyone who could not afford artificial light - candles, oil lamps and such. And this is where the answer to the question of why we no longer have two sleeps at night is to be found: artificial light. Perhaps the more important question isn’t really why we used to have two sleeps and a ‘break’ but why we stopped the practice. The wealthier classes were perhaps the first to move away from the prehistoric ‘two sleep’ pattern because of their earlier access to artificial light - candles, oil lamps, wood fires etc. The Industrial Revolution forced the proliferation of light sources and the brightness of those sources across the British Isles. Gas lights - never really ubiquitous outside of major urban centres - nonetheless opened up the night to those who had hitherto retreated from it. Once the electric lightbulb, with its powerful luminescence and lower cost, changed the British night from dark to light, the practice of two sleeps quickly faded into obscurity. No more was it necessary to stop work when the sun went below the horizon; no longer was it necessary to fear the night and barricade oneself behind locked doors. In short, people began experiencing the night (for both work and leisure) and sleeping later - to the point where the first sleep became the only sleep. In a very short period of time indeed - perhaps as little as one hundred and fifty years - your ancestors went from a nocturnal pattern of sleep that had endured for millennia whereby we slept and then woke and then slept again, to a consolidated sleep determined primarily by the growth of artificial light. Your ancestors from almost certainly followed the practice of two sleeps. What is perhaps equally important is that, since England was the first country to industrialise, they were also probably the first to abandon the practice. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (Co-Editor of Versus History) @thelibrarian6 Bibliography Ekirch, A. Roger. Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies. (http://www.history.vt.edu/Ekirch/sleep_39_03_715.pdf ) Ekirch, A. Roger. Sleep We Have Lost: Post-industrial Slumber in the British Isles (https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5f7d/10e30df23c62edc499ff26e909764e8946ad.pdf?_ga=2.82364371.494877159.1561369868-1007184158.1561369868) Koslofsky, Craig. Evening's Empire: A History of the Night in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge and New York Cambridge University Press 2011)

0 Comments

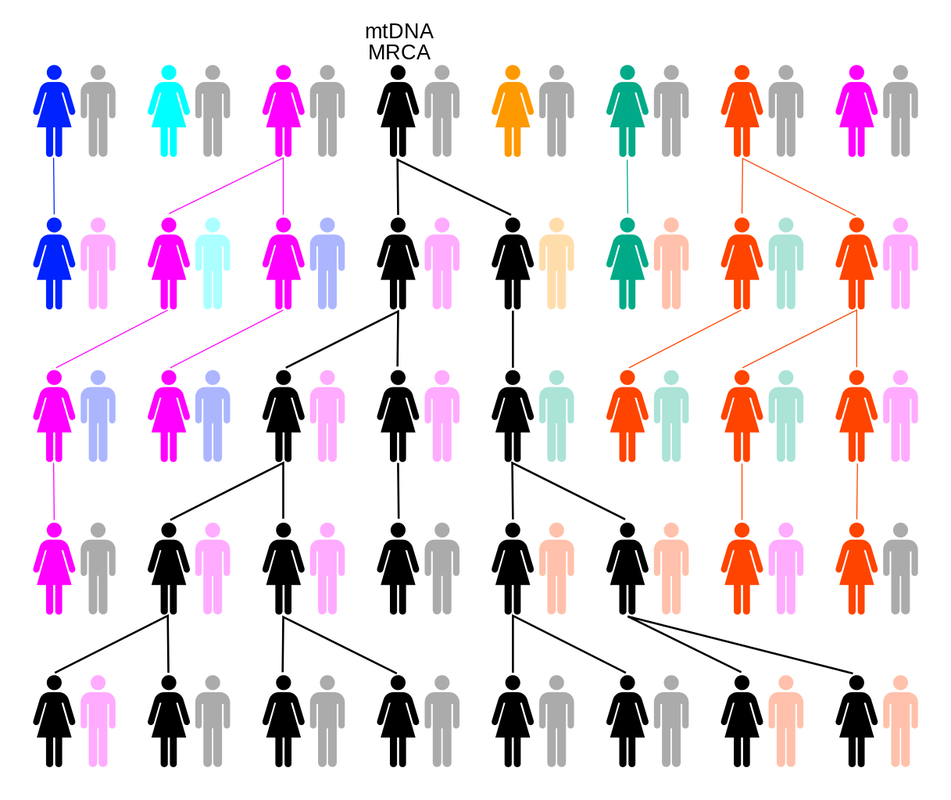

In short, yes. No matter whether you currently reside in the Americas, Europe, Africa, Australia, or Asia, you are related to royalty. It is a mathematical certainty. You are the product, in a biological and historical sense, of an unbroken line of procreation and survival, dating back in time at least as long as Homo Hominids have existed and, most probably, much, much further back than even that. Your ancestors survived for hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of years, so you could enjoy that pizza and this article. It makes sense that, particularly with the rise of genealogy websites and DNA ancestry services, people around the world are increasingly asking one particular question and, perhaps more importantly, able to have this question answered. The question is this: “Am I related to royalty?”. Regardless of the rationale driving this question - whether it be narcissism or practicality (blue blood might make you feel important and it could be very profitable in terms of inheritance rights), the question is a legitimate one - our current identity is bound so intricately (and often messily) with those who carried our blood through the millennia. We all come from somewhere. Where is that somewhere? There is also a romance to the uncovering of an ancestry either steeped in, or merely anointed by, royal blood: taking part in the achievements of our predecessors - bringing pride or infamy - can become, rightly or wrongly, part of our very own myth-making as individuals. When was the last time you told someone proudly of the achievements of your own children? Imagine if you could tell those same people that you were related to the man who overthrew King Richard III of England or the Iceni Queen who punished the Romans so defiantly. Confirmation of existence? Perhaps. Bragging rights? Most certainly. To get back to the question: “Am I descended from Royalty?”. The popular geneticist, Adam Rutherford, in his many works, including A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived, explains the irrefutable mathematics of the situation: there have been ‘only’ about 108 billion Homo sapiens. Taking as his starting point the emergence of what we may call our direct human ancestors (hominids very much like us) 50,000 years ago, Rutherford addresses a common misconception about ancestry: it does not resemble a tree, inasmuch as a tree has separate and distinct branches that extend, in a linear fashion, outwards and away from the trunk. Tree branches may have smaller branches extending outwards from them, but they are always linear - they never rejoin another branch. They exist in isolation from every other branch except the one from which they sprout. This is an impossible scenario, genealogically speaking. As we are all born of two parents*, then for the ‘family tree’ metaphor to be in any way accurate, we would expect every generation that is born to necessarily take itself one branch further away from everybody else (including the original parents and their relatives), genetically and relationally speaking - into isolation. Metaphorically, the branches should only get further and further away from the trunk of the tree, and can only stretch in two directions - backwards and forwards. Some ‘simple’ addition tells us this can’t be true. Take the following as true: You have two parents; your parents each had two parents; their parents each had two parents and so on. Add these together and go back as far as you can. 2+4+8+16+32+64 etc. If you do this and go back a ‘mere’ thousand years, the number you arrive at will be over 1 trillion. That’s 1 trillion people in your direct family tree alone. That number exceeds the sum of all humans that have ever existed - by some way. To extrapolate even further, if there are 8 billion people currently on the planet and they each have 1 trillion people in their own linear family trees, then within the last thousand years there have lived and died more than 8 sextillion humans. That’s 8 followed by 21 zeros. In only the last one thousand years. What if we went back 50,000 years - to the point in time that Rutherford and others see the emergence of Homo sapiens that could be said to correspond, in a behavioural sense, to us today? The mind boggles. And it should. So, what’s happening here and how does this relate to the question in the title? Genealogy should resemble a tangled net rather than a 'neat' tree. You see, the numbers of ancestors that we have increases exponentially as opposed to linearly; it's the difference between calculating 2+4+8+16... as opposed to 1+1+1+1… What this means, and what Rutherford, Mathematicians such as Joseph T. Chang, and Computer Scientists such as Mark Humphrys, understand is that ancestral lineage is not linear at all, it is a complicated mesh of overlapping, shared, repeated, and interconnected relationships. In short, every person on this planet is related, in a genealogical sense, to everybody else. More than this - and this is where things get particularly interesting - we all share common ancestors. Even more than this, we all share the same common ancestor/s! In order that we understand this (and do so in as simple a manner as possible) let’s go back to Africa. The most recent ‘out of Africa’ hypothesis - that all living humans are descended from Homo sapiens who emerged from, and then left, Africa between 200-300,000 years ago - rules out parallel evolution (humans evolving in different geographical locations at the same time). What this means is that, if there is only one geographical and evolutionary source for Homo sapiens, then we must, out of necessity, all be related to that source. One of the first significant elements of the human genome that was sequenced was mitochondrial DNA. Not wanting to get unnecessarily complex, mitochondrial DNA is almost exclusively inherited by children from their mothers. Combine this with the understanding of our geo-evolutionary origin (Africa) then it is an absolute certainty that every living person alive today can trace, through their mitochondrial DNA, their genealogy all the way back to a single female ancestor. We can do something similar with Y-chromosome DNA, which is passed almost unchanged from father to son. And so, in the public imagination we are all descended by an unbroken series of genetic links back to a single woman and a single man: the so-called ‘Mitochondrial Eve’ and ‘Y-Chromosomal Adam’. Mitochondrial DNA can be traced through your female ancesters. Counter-intuitively, these two individuals are unlikely to have been the first humans - they are ‘merely’ the MRCA, or Most Recent Common Ancestor, of all humans alive today. Other humans - probably millions - lived and died without leaving children to contribute to the lineage that would mesh with ours. What is perhaps even more astonishing than this is that, because of the interconnectedness of our species - helped in part by our migrations from village to village, town to town, country to country, and continent to continent - the MRCA of all people living today, probably lived just a few thousand years ago! Now that we have established our messy interconnectedness as Homo sapiens, let’s get back to royalty. Some readers may feel a little cheated by what has just been read above - the rather impersonal and blanket claim that ‘we are all related’. “Where’s the romance in that?”, one might ask. Well, let us get more specific. Using the statistical models of people such as Joseph T. Chang, we can circumvent any feeling that our general genealogical relationship to others is somehow boring, and narrow down our ancestral links to more, let us say, exciting specifics. For example, if we disregard only very recent immigration into Europe, the MRCA of all Europeans is either a man or woman who lived in the very recent past - about 600 years ago. Adam Rutherford goes one step further, demonstrating that almost every single European - and therefore anyone of European descent living in the New World - has royalty in their blood. Specifically, they have the Y-chromosome DNA of Charlemagne - Charles the Great - and/or the mitochondria of four out of his five wives. Charlemagne It is crucial to make note of something - and this is where we depart from statistics and move into history - the number of human beings currently alive that have, to any discoverable degree, documented ancestry, is miniscule. Unless your ancestors enjoyed wealth or significant historical impact, chances are there will be little to no evidence of their existence on this planet. Before the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenburg in the 1440’s, the world’s documentation was handwritten, some of which could be painstaking, most of which would be costly. Until the moveable-type printing press proliferated around the world, the fact of the matter was this: regardless of where around the world you lived and died, unless your life was viewed as worthy of documentation by someone with the means and the inclination to do so, it was likely to be forever ignored by posterity. Occasionally, bureaucracy would fortuitously record the lives of common people. For example, the Domesday Book - commissioned by William the Conqueror after his defeat of Harold of Wessex at the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and completed in 1086 - provides historians with a wonderful trove of social history. The ‘Great Survey’ of the people of England and Wales was undertaken for the purposes of taxation - William needed to assert his royal pecuniary rights over the people of his newly conquered lands and, in order to do so, needed to know the levels of wealth and property of all the people occupying these lands. Consequently, though the motive of William of Normandy was to exert his royal control, one important outcome of the Domesday Book was detailed proof of the existence of people who would otherwise have disappeared from the historical record. However, such serendipitous recording of the existence of ‘common people’ was the exception rather than the rule. In most parts of the world, well beyond the invention of the printing press or, indeed, the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the historical record was primarily oral. Unfortunately, oral history often hits the same roadblocks as written history - it mostly records the lives of only those deemed ‘worthy’ of the effort. In a very roundabout way what this means is that, depending on the geographical origins of your antecedents, the socio-economic route by which your ancestors travelled (by and large, an impoverished one), and whether or not they did something worth noting, chances are there is no evidence whatsoever of their existence. Except for you. You are the evidence of their existence. You may be the only evidence. And this brings us back to statistical models…

Since there may be little to no evidence of your genealogical history beyond your most immediate ancestors, we must take refuge in statistics. Ignoring Benjamin Disraeli’s supposed claim that “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics”, in this case the mathematics is irrefutable. If you are of European ancestry you are related to royalty. In fact, if you currently reside in the Americas - including the Caribbean and Bermuda - you are, to a high degree of certainty, related to English royalty specifically: “For example, almost everyone in the New World must be descended from English royalty—even people of predominantly African or Native American ancestry, because of the long history of intermarriage in the Americas. Similarly, everyone of European ancestry must descend from Muhammad.” (Chang) To continue, if you live in North America, whether your ancestors left from Plymouth Harbour on the Mayflower in 1620 or fled from Ireland during the potato famine of the mid nineteenth century, they took with them the DNA of royalty. Whether your ancestors were brutally enslaved and transported to the Americas in chains or were native to the land colonised by Europeans, you are related to royalty - whether it be from the royal houses of England, Europe, Africa, Asia or the Americas. It is a statistical certainty. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (Co-Editor of Versus History) @thelibrarian6 Bibliography: Chang, Joseph T. Recent Common Ancestors of all Present-Day Individuals, (Yale University 1999) http://www.stat.yale.edu/~jtc5/papers/CommonAncestors/AAP_99_CommonAncestors_paper.pdf Olson, S. The Royal We, The Atlantic (May 2002) https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/05/the-royal-we/302497/ ...many words we use in english originate from the arabic language.There are well over 300 million native Arabic speakers in the world and Arabic is an official language in over 20 countries. However, it may come as a surprise to learn that some of the words which we use in the English language today originate from the Arabic. A study of the etymology of many words with mathematical meanings and connotations will reveal that their root is in Arabic, even though they are now used in English. Here are ten words - they all begin with the letter 'A'. In some cases, they were adopted into English from intermediary languages, having already been borrowed from Arabic. So, let's take a look!

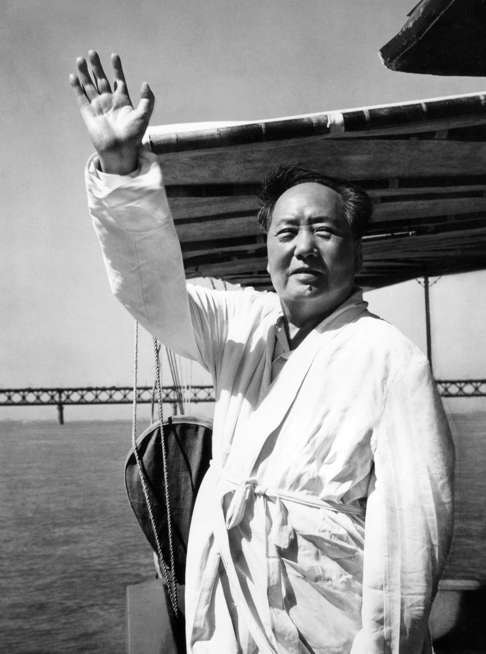

Did any come as a surprise? There are many, many more, such as Jumper, Giraffe and Candy, to name but a few. The history and evolution of languages is a complex, yet entirely fascinating one. Etymology really is something to get excited about! Patrick O'Shaughnessy (@historychappy) ...THAT CHAIRMAN MAO LIVED TO THE AGE OF 82 DESPITE A PROFOUNDLY UNHEALTHY LIFEstyle.125 years, 2 months and 13 days ago (at the time of writing) - on December 26th, 1893 - a baby boy was born in Shaoshan, Hunan. This child would, 56 years later, lead a successful communist revolution in China and serve as its unrivaled - and ruthless - leader until his death in 1976. He died at the age of 82 - something of a remarkable achievement in any country or period of history. Perhaps what is more remarkable is that, in so many respects, Mao Zedong led a life that many of us would consider dangerously unhealthy. Below is an abridged list of some of the ways in which he threw caution to the wind: He never brushed his teeth. In his 1988 memoir, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, Dr. Li, who functioned as Mao’s private physician, described how the leader’s teeth were dark green in colour and pungent in their odour. Mao followed a habit that was common among the Chinese peasantry of rinsing his mouth with tea in the morning, after which he would chew and swallow the leaves. When advice was offered that he might use a toothbrush, Chairman Mao replied that, since a tiger never brushes his teeth, then there was no reason for him to. He rarely, if ever, bathed. His refusal to brush his teeth was absolute, however, Mao’s general cleanliness, though unpalatable to most, was less so. Slightly. Other than when he occasionally went for a swim - which he famously did in the Yangtze River in 1966, marking his ‘return’ to political life after the disaster of the Great Leap Forward - he never bathed. Incidentally, when he swam in the Yangtze on that day in Wuhan, Mao set a world record swim time of 65 minutes for the 15 km distance he covered. For a 72 year old man who, to put it generously, was overweight and dangerously unfit, this ‘record’ (as it was reported by Chinese media at the time), was all the more impressive. A New York Times article entitled The Tyrant Mao, as Told by His Doctor, explained how Mao would never wash his face or hands and, other than the odd river swim, his only concession to cleanliness was an occasional ‘hot towel’ rub down from his bodyguards. Mao setting a 'world record' with his famous swim in the Yangzte in 1966 He ate. And ate. While millions of his people died of starvation during his rule, Mao never went hungry. In fact, at the Zhongnanhai Compound - the heavily guarded area within the Forbidden City - frequent parties would be thrown, the likes of which would, to quote Morrissey, “...make Caligula blush”. In addition to the sexual orgies engaged in by the Chairman, there were also orgies of a culinary kind. Mao’s favourite food - which he devoured with scant regard to portion control - was the rich hong shao rou. This dish consisted of cubes of sugar-caramelised pork belly coated with rice wine. He was a prolific spreader of STD’s Dr. Li diagnosed Mao as a carrier of trichomonas vaginalis and urged him to take an antibiotic to protect his sexual partners. Mao refused on the grounds that, since it wasn’t hurting him, it did not matter. Although it may be difficult to comprehend, the many women that he infected (and there were many) seemed to hold the disease up as a badge of honour, proving that they had been intimate with the Chairman. Wherever Mao travelled, he would have a never-ending coterie of young women brought to him to satisfy his sexual desires. It is claimed by Dr. Li that, as Mao got older the number of women required to satisfy these desires increased. As their number increased, their ages decreased. Significantly. Apparently Mao believed that the more sex he had, and the younger his partners, the longer the life he would lead. Perhaps his demanding sexual schedule is one of the reasons Mao would spend days on end dressed only in his dressing gown. Under Chairman Mao, the Chinese people were often forced to live a life of strict morality and adhere, often pathologically, to an ideological dogma that helped cause the death and suffering of millions. All the while their leader was indulging in private behaviour that would most likely have appeared, had it been made public during his lifetime, bourgeois and decadent at best; deviant, hypocritical and immoral at worst. Regardless, Mao’s scant regard to his own health and cleanliness, is staggering. Dr. Elliott L. Watson @thelibrarian6 ...the english language includes many words from the languages of the indian subcontinent?British links with the Indian subcontinent go back a long, long way. The East India Company (EIC) was founded in 1600, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. By 1763, victory in the Seven Years’ War meant that the enduring colonial power in the region until the twentieth century would be Britain, rather than France or Spain. In 1858, following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Crown took possession of India from the EIC. The subsequent ‘British Raj’ lasted until 1947 when India gained independence from the British Empire. To be sure, the English language has evolved over time, often as a result of British interactions with people from other geographical locations and cultures. Anyone who has studied Shakespeare or studied the Norman Conquest will no doubt be aware of that! Given the extensive history of the British in India, it is perhaps unsurprising to learn that many words used in the English language are actually of Indian origin. Here are just a few of them. Some might well surprise you ... Bungalow Cheetah Cushy Dinghy Juggernaut Punch (as in the drink) Pundit Pyjama Shampoo Thug It is clear, therefore, that history has made its mark on the English language. Patrick (@historychappy) ...THAT NAGASAKI WAS NOT THE ORIGINAL TARGET OF THE SECOND ATOM BOMB IN JAPAN.Mushroom cloud over Nagasaki. (US gov [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) At 8.15am on August 6th 1945, a B-29 Superfortress from the 393rd Bombardment Squadron called the Enola Gay - named after the mother of its pilot, Paul Tibbets - released a bomb carrying 64kg of uranium 235. After just under 45 seconds of freefall, Little Boy - this was the name of the atom bomb - detonated at 580 metres above the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Close to 80,000 civilians died instantly. When the Japanese Imperial Army refused to capitulate, a meeting on the US-controlled Pacific island of Guam, including such military luminaries as General Curtis Lemay and Rear-Admiral William R. Purnell, was convened to determine the next move. With no Japanese surrender forthcoming, the ‘next move’ was adjudged to be the dropping of a plutonium-based weapon, codenamed Fat Man (named by Robert Serber of the Manhattan Project after a character in The Maltese Falcon) over the city of Kokura. Kokura, in the south west of Japan was, incidentally, the secondary target had Hiroshima been cloud-covered on the 6th of August. Now it was the primary target. 'Fat Man' being sprayed with plastic on the island of Tinian At just after 3.45am on the 9th of August, another B-29 Superfortress - this time named Bockscar - took off from the island of Tinian in the Pacific Ocean, loaded with Fat Man, and headed towards the Kokuran military arsenal. After rendezvousing with support planes above Yakushima Island, Bockscar flew onto Kokura. For a good portion of the final months of the war in the Pacific, the USAF had been firebombing the mostly wooden cities of Japan in the hopes of causing such terrible civilian casualties and damage to property that the High Command would be forced into surrender. During the previous day, American bombs had set fire to the nearby city of Yahata. The smoke that continued to billow from the city obscured the primary target of Kakura such that, despite three bombing runs above the target, the Bockscar could find no opening in the cloud cover. As a result, the secondary target was selected. Nagasaki, and not Kokura, would bear the brunt of history’s atomic age. B-29 Superfortress, Bockscar. (ASAF [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) Two minutes before any clock in Nagasaki struck 11am, Fat Man fell from Bockscar. 43 seconds later, one gram of matter (from the 6.19kg of plutonium) was converted into heat and radiation 500 metres above the ground. Approximately 40,000 Japanese people died almost immediately. The number of deaths would have been far higher had it not been for the mountainous topography of Nagasaki which helped shield some residents from the blast. As it was, tens of thousands died from leukaemia and other radiation-related illnesses, as well as the fires that raged long after. Atomic cloud over Nagasaki from Koyagi-jima(Hiromichi Matsuda (松田 弘道, ?-1969) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons) Dr Elliott L. Watson

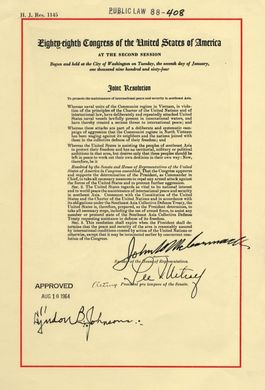

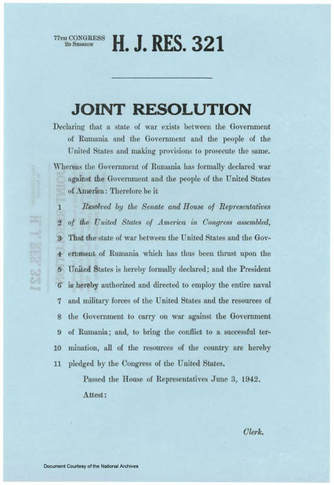

@thelibrarian6 The ‘Tonkin Gulf Resolution’, August 10th, 1964 Our recent Versus History podcast was a fifteen-minute special in which Patrick asked me some quick-fire questions in the allotted time on one of my particular areas of interest. The area of interest that I elected to have questions fired at me upon was American involvement in the Vietnam War. For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by the Vietnam War. I am very much aware that the term ‘fascinated’ is perhaps wholly inappropriate a verb to employ when discussing an event in which countless numbers of people lost their lives, and one which still carries a present-day legacy of physical and emotional trauma, but it is, to me, the right word to use. It is entirely possible that my fascination was conceived during my early to mid-teens when I would spend school lunchtimes at a friend’s house watching (among a number of movies I wasn’t supposed to watch at such a tender age) the Oliver Stone film, Platoon. The horror of the conflict and the stark and complex differences between the ‘soldiers’ on both sides, as well as the differences between the American soldiers themselves, made for a jarring, unsettling viewing experience. The more I learned and, later, taught about American involvement in the Vietnam War, the more it became clear to me why it was so, enigmatic. Again, you may think this a terrible choice of adjective to describe an event of such tragedy and horror - and for the most part, you would be correct in your thinking, except that... Ask yourself this question: When did the Vietnam War begin? Go one further and ask yourself: When did American involvement in Vietnam begin? The enigma that I speak of is bound up in these two questions. It used to be that wars were a largely formal affair - war was declared, lines were drawn, sides were assembled, and battle commenced. The United States has not issued a formal declaration of war since June 4th 1942, which was against Rumania. Of course, to suggest that the United States has been entirely uninvolved in direct military conflict since 1942 would garner immediate incredulity. However, the fact still stands: the United States Congress (for it is only the legislature which can do so) has declared war ‘only’ eleven times in its history, starting in 1812 against the British, and ending in 1942 against the Rumanians. And therein lies the rub. As historians of conventional wars, we can place our finger on a date in a calendar, or a mark on a timeline and declare with the utmost of confidence, “Here, here is where the war starts!”. With the conflict in Vietnam, we can have no such confidence because we can do no such thing. US Declaration of War on Rumania, June 4th 1942 All of what we would call modern day Vietnam (as well as many of its surrounding neighbours - often referred to collectively as Indochina) had been colonised and ruled, almost without break, for hundreds of years by various foreign interlocutors - from China, to France, to Japan, back to France, and then - according to most Vietnamese - to the United States. Each subsequent incoming coloniser (for that is how they were most certainly viewed by the vast majority of the people of Vietnam) came into the country immediately upon the heels of the outgoing coloniser. In some cases, the outgoing invader was forced out by the incoming invader. In some cases, the invader was chased out by the Vietnamese themselves. In other cases - one of particular note - the outgoing occupier (a failing France) asked for assistance from someone they hoped would take on some of the burden of ruling Vietnam - the United States.

Since there is no declaration of war to which we can point as the ‘start’ of the war, then the language we employ must shift to accommodate the vagaries of a war without one. The term we generally use in our investigation is ‘involvement’. In many ways this word is a poor substitute for ‘beginning’ or ‘start’ - instead of making things clearer, the new semantic actually makes murkier the already murky water. Ask any Historian to determine the origin of a war, and expect a deep inhalation of breath before they begin. Ask any Historian about the origin of involvement in a war, and you had better tell your husband or wife that you’ll be late home for dinner. The reason? How do you quantify involvement? How do you qualify involvement? By what criteria do you judge involvement? What does involvement even mean? You know what I mean? Take a deep breath... Without a declaration of war, at what point would you consider America to be involved in Vietnam? If a president utters public phrases criticising French occupation of Vietnam, does that represent a public investment in the concerns of the country? If a president begins discussing who should rule Vietnam once World War Two is over and the Japanese are defeated, does this constitute American involvement? FDR did both of these things. If American soldiers, including Major Allison Thomas, as part of an OSS (Office of Strategic Services) mission had parachuted into North Vietnam to train Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh guerrillas to help prevent Japanese escape and gather intelligence, would this constitute American involvement in Vietnam? This happened in the dying days of World War Two, under President Truman. In order to guarantee French support in NATO, and to avoid a Cold War power vacuum being created by a French loss in Indochina (who were now fighting the Viet Minh), Truman authorised millions of dollars in financial and military assistance to the French. Would this be considered US military involvement in Vietnam? President Eisenhower gave billions of dollars worth of aid and provided 1500 military advisors to Diem (the leader of South Vietnam) who helped establish the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam). He even guaranteed that he would support Diem if he chose not to hold the free elections that had been called for under the Geneva Accords of 1954. Would this be considered involvement? Remember, at this point in time - 1954 - there are no American ‘boots on the ground’. When the French lose at the Battle of Dienbienphu in 1954 and decide to leave Vietnam for good, America already has a financial, military and ideological commitment to the security of South Vietnam. And yet… no war. When JFK, in 1956, gives a speech determining that ‘Vietnam is the place”, is he foreshadowing an increased involvement? When Kennedy becomes the President and increases financial and military assistance, including helicopters and pilot ‘advisers’, authorises the use of Agent Orange and Napalm, increases the number of military ‘advisers’ to 16,000 by 1963, creates the MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam), secretly sends Green Berets, and authorises the Strategic Hamlets Programme, is America involved? Remember, there are still no official US soldiers fighting and there is no Congressionally recognised war. When President Johnson convinces Congress to pass, what was known as, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, authorising presidential discretion in terms of a military response, is America involved? Is it involved at the point at which Operation Rolling Thunder begins, in 1965, bombing the jungles and villages of North Vietnam, dropping more ordinance than was dropped on Europe during the entirety of World War Two in the process? Is it involved when LBJ authorises an escalation of over half a million troops to assist the government of South Vietnam fight against the Vietcong and the Viet Minh? Exhausting, right? And remember, still no declaration of war by the US Congress. Thank you for bearing with me. Let me synthesise:

Where does this leave the student of American involvement in Vietnam? It leaves you with an interesting and unique opportunity: you get to choose both the meaning of the word ‘involvement’ and determine the point at which you consider the US to be involved. That’s what is so wonderful about the subject of History: provided you maintain an honest commitment to the evidence, you get to set the parameters of your investigation. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (@thelibrarian6) Co- Editor, Versus History |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed