...ronald mcdonald has been a mcdonald's mainstay since the 1960s?McDonald’s probably has one of the most instantly recognisable brands in the world. Since its inception in San Bernardino, California in the 1940s, the fast-food restaurant chain has gained a truly global footprint, with well over 35,000 branches in over 100 different countries. That is pretty impressive. The Happy Meal, the Big Mac and the McFlurry are just some of the McDonald’s product range. When it comes to advertising the ‘McDonald’s’ brand, the ‘Ronald McDonald’ clown character has been a core feature of its promotional efforts, dating back to the same year that the USSR put the first woman - Valentina Tereshkova - into space. That was 1963! Since Ronald’s debut, the mythical character has had an interesting history. Here are just a few of Ronald’s 'history highlights' ... 1) Ronald McDonald’s early appearances in TV adverts indicated that he was a resident of an imaginary cartoon world known as ‘McDonaldland’, which he shared with the Hamburglar, amongst others. ‘McDonaldland’ landscape cartoons were a regular feature on the walls of McDonald’s restaurants in the 1980s, but these were gradually phased out and often replaced with more sober and corporate style imagery. 2) Ronald McDonald is not the only cartoon mascot for a fast-food burger restaurant chain. Wimpy - who were in direct competition with McDonald’s in North America and Europe in the 1970s and early 1980s - had their very own ‘Mr Wimpy’. 3) Ronald McDonald was a regular visitor to children’s parties across the world in the 1980s and 1990s. Anyone who hosted or visited an event at a McDonald’s restaurant around this time might have been lucky enough to receive a visit from the clown character himself. The author of this article has many such happy memories of Ronald. While Ronald McDonald remained a pivotal plank of the promotional activities of McDonald’s franchises in the Far East between the late 1990s-2010s, he was far less visible in Western Europe during this time. Indeed, in this geographical area, the chain largely mothballed the character. Ronald did, however, make occasional appearances in Happy Meal toys and promotions from time-to-time. Officially, Ronald McDonald was never retired and he remains a facet of the McDonald’s corporate image to this very day, albeit a less visible one in some areas.

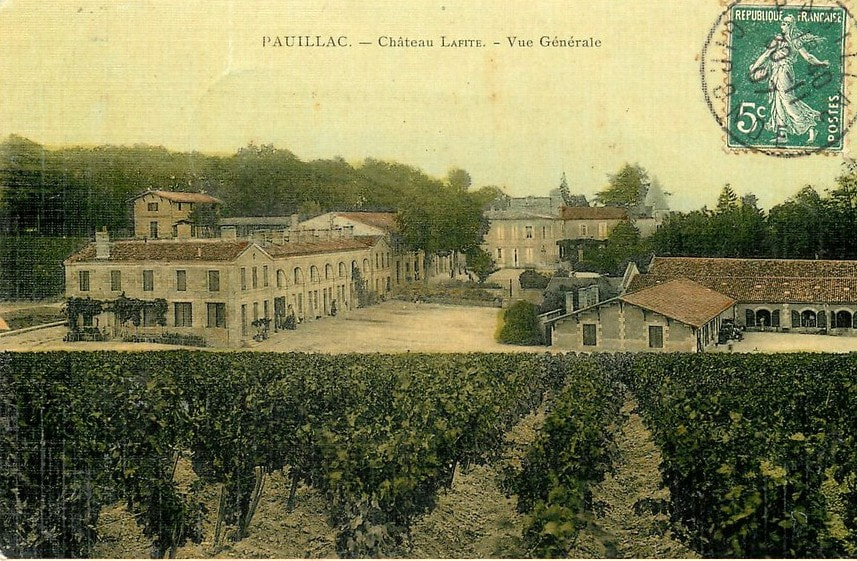

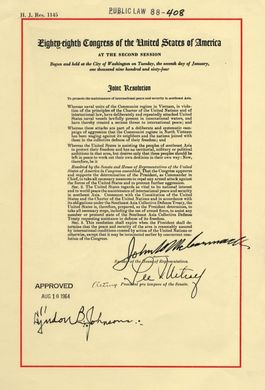

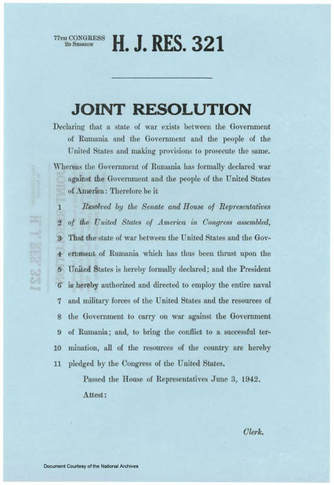

Patrick O'Shaughnessy (@historychappy) Executive director of trance hotels, graduate of École Hôtelière de Lausanne, and certified Court of Master Sommeliers, Suryaveer singh, takes us through the incredible history of wine.Benjamin Franklin once said “Wine is constant proof that God loves us and loves to see us happy”. The world of wine has a dark and mysterious past filled with ups and downs which run parallel to our very own existence as humans. In the mid-1970s a group of Archaeologists, working in the ancient site of ‘Khramis- didi- Gora’ in present day Georgia, stumbled across an artifact which would augment our understanding of the drink we know as wine. The artifact was an 8,000 year old Neolithic jar with fine engravings of grapes on it, used as a vessel in which to crush wine grapes and brew the delicate liquid which represented the terroir and love of the land. Such is the history of wine that it is intertwined with humanity’s history- wherever a civilization was set to thrive and flourish, the evidence of wine being grown is present. From the very moment the Ancient Chinese in 6000 BC discovered the art of fermenting crops into alcohol, humanity has twisted and turned alcohol recipes to suit palates for different ethnicities - be it beer or fortified rice wine. However, the terrain of modern-day Europe turned out to be ideal to grow wine through grapes and thus started the friendship of the Homo Sapien with wine. ‘Khramis- didi- Gora’ wine jug Wine seemed to serve numerous purposes for man - it was a safer to consume beverage over water, it was relatively easy to grow and consume, it was a valuable barter item, it was an ideal beverage to enjoy with food, the drink could be stored for longer periods and all sections of societies enjoyed it. The appreciation of wine in society is made visible with engravings of how to make it in the Pyramids of Giza in 2580 BC: King Tut’s tomb had countless wine jars for him to take to the after-life. On 197 occasions, the Old Testament mentions wine and refers to the beverage as ‘the blood of Christ’. Caesar used to command his mighty Roman army to consume up to 3 litres of wine a day/per soldier. Even Leonardo da Vinci didn’t shy from placing Jesus’ hand reaching for a glass in his iconic ‘The Last Supper’. Wine plays an integral part in mapping the history of Europe. Wine was introduced to the Mediterranean – present day Italy – by the Phoenicians in about 1550 BC, and the Roman Empire brought the crop from there to France. Throughout this time, the local population, through trial and error, figured out the most perfect and fertile plots of land to grow and perfect wine. One can examine the history of the renowned vineyards of Bordeaux in North Western France, which were historically under swamp water but drained by Dutch engineers in the 1600s’, as an example. The Dutch eventually farmed this land and turned it into a gravel and clay based soil – an ideal combination to grow award-winning wines. This new soil happened to bear fruit for the best wine making regions of Haut Medoc, and for wineries like Chateau Margaux and Chateau Lafite, which went on to be recognized by Napoleon and eventually the world as some of the greatest wines of our times. Chateau Lafite Winery The Romans perfected wine maturing in barrels along with the usage of hardened glass to protect the delicate liquid and showcase its most pure character. With wine thriving in Europe thanks to the Renaissance, the beverage was soon exported across the continent and throughout nations further afield through colonization. The discovery of the Americas, South Africa and Australia in the 1600s saw settlers bringing their favorite vines to new shores – George Washington being an avid wine grower himself. The New World, as it was referred to, had less rain and strong summers, which helped to ripen the fruit and bring about a more fruity flavored taste compared to the more mineral flavors in the European mainland. The 17th century was a seminal year for grape wine, with a sparkling variety of the beverage being introduced through sheer chance by a Christian monk named Dom Perignon in the Northern French town of Champagne. The world-of-wine now had a beverage to mark celebratory occasions. In 1703, tensions between the French and the British led to the development of Portugal growing wine of their own to feed the demand of Anglophiles. Portugal and Spain’s wine culture was disrupted under the rule of Islamic conquerors from 792AD to 1492AD. Greek youth using an 'oinochoe' or wine jug. 490-480BC The history of wine, however, does have a dark side. The beverage almost met its demise in the period from 1860 to 1890 due to an insect named Phylloxera which would chew the vines and ruin the fruit. Wine production from all countries dropped to a quarter in this period and with the growing popularity of alcoholic spirits, the wine market neared collapse. The industry finally figured out how to evolve their vines to withstand the bug and started to focus on the more common grape varieties of today- Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir and Chardonnay. The 20th century gave the industry a new challenge: with growth of the global population from 1.6 Billion in 1900 to 6.1 Billion in 1999, wine growers had to increase supply and adopt technology to rid themselves of archaic methods in order to improve their yield and quality. Two world wars caused a drop in production: the vineyards of Champagne were scenes of battle trenches, and cellars were looted. The state of Alsace in France, bordering Germany, exchanged occupation between the two warring countries, which resulted in the region producing German Rieslings with French finesse still to this day. The United States’ wine industry faced a devastating blow in the 1920s thanks to prohibition, which saw century-old vines uprooted and discarded. The industry lay dormant and discouraged until the 1960s. In 1966 an American called Robert Mondavi invested large sums of money to kick-start his very own winery in Napa, California. Mondavi’s winery encouraged others to follow suit and thus the golden age of New World wines began, with Californian wines often defeating their French superiors in blind tasting competitions. The New World, which comprised of non-European nations, adopted new techniques and methods such as temperature-controlled vats to ensure wine quality and screw caps to appeal to a new market. Today the New World produces more wine than any other single country. In 2019, the $423 Billion a year industry is at an exciting stage with strong demand from cash-rich China, overtaking the markets of Britain and France. With technology, wine growers are aiming to grow the grape in regions where, previously, none would have been deemed possible thanks to their long summers – India, China and Indonesia. Whatever we may see in the future, with global warming and the advent of artificial intelligence – wine will continue to remain man’s true companion, to sit beside him as one enjoys the fruits of life.  Suryaveer Singh, Executive Director of Trance Hotels Instagram: curious_sommelier I can spot a skater from a mile off. Identification doesn’t rest on something as simple as the clothes they are wearing or the hair they are styling. And it isn’t because they are carrying a skateboard. It’s something...different; not quite an attitude, more a “type of movement”, as freestyle/street legend Rodney Mullen put it (1). Mullen believes there is an authenticity to skateboarding which transcends the annual fashion trends and is embedded in skateboarding’s rebellious genetic constitution. I happen to agree with him - but this isn’t a philosophical blog post - this is historical. It was around the age of 9 or 10 that I began, what would evolve into, a permanent passion for all things skateboarding. Somehow (I don’t recall how) I came into possession of a ‘Penny Board’ - a narrow fibreglass and plastic skateboard, the type of which you see at any toy store. Mine had a ‘Stars and Stripes’ design on the top but I don’t remember the colour of the wheels. This was the first in a long line of boards that I would purchase and ride over the next 12 years. I still purchase decks (at the age of 44!) but now I buy them for the nostalgia and the artistry of each deck. My first real full size professional board was a Santa Cruz, Rob Roskopp ‘Target IV’. I had begged my parents to buy me one for my birthday. When it arrived, it became my most prized possession - I remember vividly the shape and the feel of it under my feet. I recall spending hours ‘designing’ my grip-tape pattern on the surface of the board. But this isn’t a blog for the sake of nostalgia - this is historical.i] Iterations of Santa Cruz's Rob Roskopp 'Target' Deck. Identifiable origins on the evolutionary timeline of skateboarding can be found in the 1940’s and 1950’s. The evolutionary ‘single-cell’ of skateboarding must be the ‘crate scooter’ or ‘crate-skate’. American children (or, as is more likely, their parents) took empty fruit crates and nailed them to planks of wood, which themselves were set atop metal roller skate wheels. If you have ever watched the first Back to the Future film, you will see Michael J. Fox steal a kid’s crate scooter, rip the crate from its plank of wood, thus creating a skateboard. You then see him (actually his skate-double, professional rider Per Welinder) evade Biff and his bullies by using his 1980’s skills on his 1950’s board. Undoubtedly, these crates carried within their rudimentary design, the DNA of their future progeny, but skateboarding (as we know it today) was really a product of the 1960’s surf scenes in California and Hawaii. Looking for ways to occupy their time and energies when waves were not forthcoming, surfers began transferring their skills to land. Roller skate wheels were screwed to simple planks of wood that surfers would ride barefoot along the sidewalks - thus ‘sidewalk surfing’ was born. Surf companies, quick to pick up on the new trend, began building complete set-ups for sale - some of the more influential being, Hobie, Bing’s and Makaha. Embedded in the genetic blueprint of this early incarnation of skating, was the 1960’s counter-cultural philosophies of rebellion and independence. Skateboarding has changed since then - the boards, the wheels, the fashions, the tricks, the appeal, the marketability, have all evolved beyond measure. One absolute constant, however, is the non-negotiable nature of what it means to be a skater - a dedication to self-improvement (in skateboarding) and a comfort with remaining outside of mainstream social, cultural and political trends. Perhaps the earliest successful embodiment of this ‘nature’ was the Zephyr Team (known more popularly as the Z Boys). Immortalised in the film, Lords of Dogtown (directed by Christine Hardwicke and starring Heath Ledger), the Z Boys (Stacy Peralta, Tony Alva and Jay Adams, to name a few) oversaw an evolution in skateboarding, with their low, fast and aggressive lines pushing the domain of skating into the air and into empty swimming pools. As mentioned in the podcast, there were a number of turning points in the development of skateboarding - I’ve picked three which I believe to have had tremendous impacts: 1) The invention of urethane wheels, 2) The creation of the ‘ollie’, and 3) The use of VHS recording technology. Urethane Wheels Until the invention of the urethane wheel, skateboards ran on metal wheels with little to no grip or control. When Frank Nasworthy introduced this new type of wheel in 1972, creating the company Cadillac Wheels, he revolutionised the emerging sport. With the grip and speed afforded the rider, skaters were now in control of their boards in a manner impossible with metal wheels. This pushed the envelope of technical ability and accelerated trick development. None of today’s tricks would be possible without the ‘ball-bearinged’ urethane wheel. It also ushered in the era of wearing sneakers to skate, instead of riding barefoot. The ‘Ollie’ In the 1960’s, skaters would ride their board barefoot and, should they wish to jump, would either simply leap from their board over an obstacle (think of a high jump where the rider goes over the bar and the board glides underneath it) or, by gripping the board with their toes - the ‘gorilla grip’ - and pulling the board with them when they jumped. This, as you can imagine, limited the trickset that any rider could master. That is, until Alan Gelfand invented the ‘ollie’ in 1977/78. Gelfand was able to air out of a vertical section of Solid Surf Skate Park in Florida without holding onto his board with his hands or feet. This was a truly staggering development as it introduced a new range of aerial tricks that were possible, as well as enabling skaters to ‘pop’ much higher out of the half-pipes, bowls, and pools. The trick was immediately monickered the ‘Ollie Pop’ after its inventor, whose nickname was ‘Ollie’. In the 1980’s, Rodney Mullen was able to recreate the ‘ollie’ on flat land - and thus street skating was born. Pretty much any street skating trick you care to select, is dependent upon the ‘ollie’. VHS Skateboarding was very much an American phenomenon and, as a result, other than Americans who exported the sport abroad when they travelled (American soldiers did this very thing when serving in Germany during the 1970’s), it remained largely bound by the borders of the United States. That is, until, the development of VHS recording technology enabled skate companies to film their teams and market their brands abroad, relatively cheaply. Early pioneers of this format, were Powell-Peralta, with their wildly popular Bones Brigade videos, H-Street, who produced low budget, gonzo-style videos which introduced the world to legends such as Matt Hensley, Danny Way, and Tony Magnusson, and Santa Cruz - the original home of the near-mythic Natas Kaupas. All of a sudden, these brands and their skaters had a global reach. Consequently, new tricks could be learned by kids all around the world, companies became multinational (and wealthy), and skaters like Tony Hawk and Mark Gonzales emerged as superstars. Let’s not forget that directors such as Spike Jonze got his start directing skate videos (see the groundbreaking Video Days starring - the now famous actor - Jason Lee). My passion for skateboarding and push for proficiency in new tricks was, in no small part, due to the availability of a steady stream of skate vids on VHS. The success of shows such as Jackass owes a great debt to both the culture of skateboarding and the media through which it was transmitted. This has been very much a rapid-fire exposition of some of the core elements of the development of skateboarding - most of which have been selected because of a selfish interest in those particular areas. If you are interested in how the modern form continues to inspire and push boundaries (some of the street skating happening around the world currently, is beyond what I could have comprehended thirty years ago), then you could do worse than to visit www.theberrics.com, try and catch a Street League show, or get yourself a copy of Transworld Skateboarding or Thrasher Magazine. If you want to see how boards and designs have changed over the decades, I would recommend The Disposable Skateboard Bible, by Sean Cliver. Dr. Elliott L. Watson Co Editor of Versus History 1 http://www.scmp.com/magazines/style/people-events/article/2107340/skateboarding-legend-rodney-mullen-says-its-all-about. The ‘Tonkin Gulf Resolution’, August 10th, 1964 Our recent Versus History podcast was a fifteen-minute special in which Patrick asked me some quick-fire questions in the allotted time on one of my particular areas of interest. The area of interest that I elected to have questions fired at me upon was American involvement in the Vietnam War. For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by the Vietnam War. I am very much aware that the term ‘fascinated’ is perhaps wholly inappropriate a verb to employ when discussing an event in which countless numbers of people lost their lives, and one which still carries a present-day legacy of physical and emotional trauma, but it is, to me, the right word to use. It is entirely possible that my fascination was conceived during my early to mid-teens when I would spend school lunchtimes at a friend’s house watching (among a number of movies I wasn’t supposed to watch at such a tender age) the Oliver Stone film, Platoon. The horror of the conflict and the stark and complex differences between the ‘soldiers’ on both sides, as well as the differences between the American soldiers themselves, made for a jarring, unsettling viewing experience. The more I learned and, later, taught about American involvement in the Vietnam War, the more it became clear to me why it was so, enigmatic. Again, you may think this a terrible choice of adjective to describe an event of such tragedy and horror - and for the most part, you would be correct in your thinking, except that... Ask yourself this question: When did the Vietnam War begin? Go one further and ask yourself: When did American involvement in Vietnam begin? The enigma that I speak of is bound up in these two questions. It used to be that wars were a largely formal affair - war was declared, lines were drawn, sides were assembled, and battle commenced. The United States has not issued a formal declaration of war since June 4th 1942, which was against Rumania. Of course, to suggest that the United States has been entirely uninvolved in direct military conflict since 1942 would garner immediate incredulity. However, the fact still stands: the United States Congress (for it is only the legislature which can do so) has declared war ‘only’ eleven times in its history, starting in 1812 against the British, and ending in 1942 against the Rumanians. And therein lies the rub. As historians of conventional wars, we can place our finger on a date in a calendar, or a mark on a timeline and declare with the utmost of confidence, “Here, here is where the war starts!”. With the conflict in Vietnam, we can have no such confidence because we can do no such thing. US Declaration of War on Rumania, June 4th 1942 All of what we would call modern day Vietnam (as well as many of its surrounding neighbours - often referred to collectively as Indochina) had been colonised and ruled, almost without break, for hundreds of years by various foreign interlocutors - from China, to France, to Japan, back to France, and then - according to most Vietnamese - to the United States. Each subsequent incoming coloniser (for that is how they were most certainly viewed by the vast majority of the people of Vietnam) came into the country immediately upon the heels of the outgoing coloniser. In some cases, the outgoing invader was forced out by the incoming invader. In some cases, the invader was chased out by the Vietnamese themselves. In other cases - one of particular note - the outgoing occupier (a failing France) asked for assistance from someone they hoped would take on some of the burden of ruling Vietnam - the United States.

Since there is no declaration of war to which we can point as the ‘start’ of the war, then the language we employ must shift to accommodate the vagaries of a war without one. The term we generally use in our investigation is ‘involvement’. In many ways this word is a poor substitute for ‘beginning’ or ‘start’ - instead of making things clearer, the new semantic actually makes murkier the already murky water. Ask any Historian to determine the origin of a war, and expect a deep inhalation of breath before they begin. Ask any Historian about the origin of involvement in a war, and you had better tell your husband or wife that you’ll be late home for dinner. The reason? How do you quantify involvement? How do you qualify involvement? By what criteria do you judge involvement? What does involvement even mean? You know what I mean? Take a deep breath... Without a declaration of war, at what point would you consider America to be involved in Vietnam? If a president utters public phrases criticising French occupation of Vietnam, does that represent a public investment in the concerns of the country? If a president begins discussing who should rule Vietnam once World War Two is over and the Japanese are defeated, does this constitute American involvement? FDR did both of these things. If American soldiers, including Major Allison Thomas, as part of an OSS (Office of Strategic Services) mission had parachuted into North Vietnam to train Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh guerrillas to help prevent Japanese escape and gather intelligence, would this constitute American involvement in Vietnam? This happened in the dying days of World War Two, under President Truman. In order to guarantee French support in NATO, and to avoid a Cold War power vacuum being created by a French loss in Indochina (who were now fighting the Viet Minh), Truman authorised millions of dollars in financial and military assistance to the French. Would this be considered US military involvement in Vietnam? President Eisenhower gave billions of dollars worth of aid and provided 1500 military advisors to Diem (the leader of South Vietnam) who helped establish the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam). He even guaranteed that he would support Diem if he chose not to hold the free elections that had been called for under the Geneva Accords of 1954. Would this be considered involvement? Remember, at this point in time - 1954 - there are no American ‘boots on the ground’. When the French lose at the Battle of Dienbienphu in 1954 and decide to leave Vietnam for good, America already has a financial, military and ideological commitment to the security of South Vietnam. And yet… no war. When JFK, in 1956, gives a speech determining that ‘Vietnam is the place”, is he foreshadowing an increased involvement? When Kennedy becomes the President and increases financial and military assistance, including helicopters and pilot ‘advisers’, authorises the use of Agent Orange and Napalm, increases the number of military ‘advisers’ to 16,000 by 1963, creates the MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam), secretly sends Green Berets, and authorises the Strategic Hamlets Programme, is America involved? Remember, there are still no official US soldiers fighting and there is no Congressionally recognised war. When President Johnson convinces Congress to pass, what was known as, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, authorising presidential discretion in terms of a military response, is America involved? Is it involved at the point at which Operation Rolling Thunder begins, in 1965, bombing the jungles and villages of North Vietnam, dropping more ordinance than was dropped on Europe during the entirety of World War Two in the process? Is it involved when LBJ authorises an escalation of over half a million troops to assist the government of South Vietnam fight against the Vietcong and the Viet Minh? Exhausting, right? And remember, still no declaration of war by the US Congress. Thank you for bearing with me. Let me synthesise:

Where does this leave the student of American involvement in Vietnam? It leaves you with an interesting and unique opportunity: you get to choose both the meaning of the word ‘involvement’ and determine the point at which you consider the US to be involved. That’s what is so wonderful about the subject of History: provided you maintain an honest commitment to the evidence, you get to set the parameters of your investigation. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (@thelibrarian6) Co- Editor, Versus History |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed