|

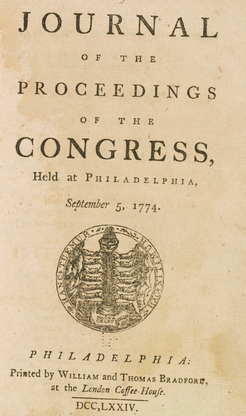

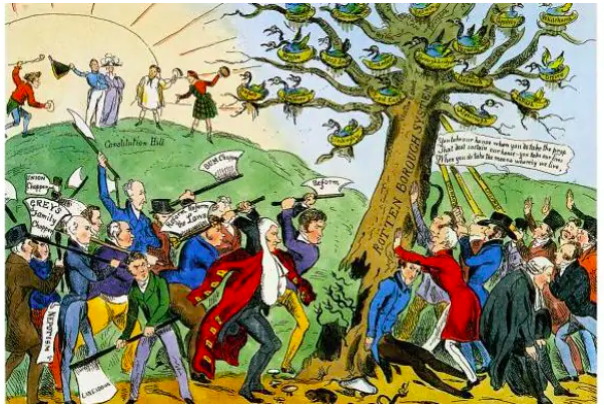

In the current UK political climate it is not uncommon to hear that democracy is under threat, with people of many different outlooks discussing the extent to which ‘the will of the people’ is being either adhered to or ignored. Implicit among all claims however is the idea that the United Kingdom has a rich history of democracy. This may be true in relation to some other countries, but it does not actually go back quite as far as one might think. The traditional starting point of British democracy is the signing of Magna Carta in 1215, a legal document that placed limits on the absolute power of the King. Magna Carta stated many things, establishing trial by jury as a right for all free men, giving liberties to the Church and London, but it also necessitated the consultation of a ‘Great Council’ by the monarch in their rule. This council was far from democratic, being made up only of the greatest magnates and power holders in the land. However, it did mark the end of the ‘absolute’ right to rule of English monarchs and denote that there would be some element of people power in the governance of England. The principles of Magna Carta have spread through much of the world, including to the North American continent. Indeed, if you look at the proceedings of the First Continental Congress of 1774, in some senses initiating the move away from British rule and to American Democracy, the title page contains an image of liberty adopted by the Congress with Magna Carta as its base. There is some irony here. In England, Magna Carta far from ushered in a representative democracy such as citizens on either side of the Atlantic would recognise today. We should not look back to Magna Carta as ushering in representative democracy. So then, what were the chances, even if we go back just a couple of hundred years of an average British person having the vote in a representative democracy? In short, unless they came from the upper echelons of society the chance that they had the vote until extremely recently (in historical terms) is very slim. Firstly we can categorically rule out half of brits having the vote solely on the basis of their sex. With the exception of a few anomalies such as the Isle of Man (ironically), Tuscany and Finland, women were not granted the right to vote until the end of WWI. Even the anomalies preceded the end of WWI by only a few decades and these are statistically so small as to be discounted. Yet the chances of a specific briton having the vote is little better. The first key date on which the answer to this question depends is 1832. The political system used within the British Isles, and the concomitant right to vote, was more or less the same from late medieval times until the so called ‘Great Reform Act’ of 1832. This was the first of a series of laws passed which expanded the number of people who could vote in England and Wales, with a similar law also passed in Scotland and Ireland (at that time under direct British rule). If your ancestors left the British Isles before 1832 they were highly unlikely to have had the vote under this unreformed system. In Scotland, the best estimate of people who were qualified voters is just 0.2%, with the MP for the capital of Edinburgh chosen by the votes of just 33 people! Things were slightly better in England with your male ancestors having a roughly 1 in 25 chance of qualifying to vote. A 4% chance may sound reasonable, even if the way in which one was qualified as eligible to vote was anything but. The country was a patchwork quilt of different systems. In the County constituencies (in effect rural areas), the qualification had been established in 1430, that to qualify as a voter one needed to own (and specifically not rent!) land worth a minimum of 40 shillings. In some counties such as Middlesex this could equate to just 0.22% of people having the vote. If one came from more urban areas, they would have lived within a borough constituency. The borough constituencies of England and Wales had no uniform qualification for voting and their size varied from the infamous Old Sarum, which was a ‘rotten’ borough with ‘no house nor vestige of a house’ yet it still returned two MPs, with the owners of certain sections of a field eligible to vote! Other constituencies, nicknamed pot-walloper boroughs, required that a man not claim poor relief and had a fireplace big enough to boil a certain size of pot! Additionally, if you were a member of the town council in a corporation borough, owner of a specific house in a burgage borough or a payer of poor relief in a scot and lot borough, then, in a rather convoluted manner you had the right to vote.

Sadly, even if they did have the right to vote, many british people were never given the chance to exercise their right. While there were elections at least every seven years, there was every chance that in a constituency there would be an uncontested election with only one candidate. In the 1831 elections, the last before these reforms, only one third of elections were contested (and even in 1910 25% went uncontested!). Matters did improve after 1832, though not very much. Estimates vary but the number of eligible voters jumped from about 4% to somewhere about 6%. Groundbreaking. Come the late 1860s and the passing of a Second Reform Act in 1867, the number of eligible voters jumped to somewhere in the region of 32% of males, with a further jump to nearly 60% after further reform in the mid 1880s. So there we have it, before 1832, an average Englishman had at best a 4% chance of having the right to vote (if they were male) and only a one in 3 chance (so 1.33% overall) of being able to use that, while any Scotsmen had an even lesser chance of doing so. It does make you wonder which history we're remembering at times.... Conal Smith @prohistoricman Bibliography Blackburn, R. The Electoral System in Britain Fisher, D. R. The House of Commons, 1820-1832, History of Parliament Trust, 2009, Vol III Houston, R. Scotland: A Very Short introduction

1 Comment

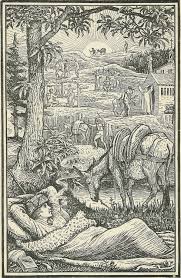

If you are waking up right now, chances are you have had, what clinicians term, one period of consolidated sleep. That is, you went to bed yesterday evening and awoke the following day - this morning. In most parts of the world - particularly the industrialised world - consolidated sleep is the norm. By and large, our patterns of sleep and wakefulness (known as our circadian rhythm) are governed by two things: the cycle of nighttime and daytime; the daily demands on our time. The former is mandated by the movements of the planets (not much we can do about that), the latter is determined by a multitude of factors, perhaps the most significant being the daily work that we have to do. In a sense, for the vast majority of people, we don’t have much control over this either. The Industrial Revolution and state-sponsored education have tended to organise the daily routines of most people around the world, meaning that - exceptions notwithstanding - we carry out our ‘work’ during one continuous block during the day and sleep in one continuous block at night (if we are lucky). It was not always the case. In fact, until relatively recently your ancestors would most probably have maintained a bi-modal sleeping pattern. They had two sleeps a night. In At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past, Roger Ekirch’s revelatory investigation into the social history of what people around the world do at night, a rich and varied trove of evidence from across the centuries and the globe, suggested that we had a ‘first sleep’ and then a ‘second sleep’. The first sleep began a couple of hours after the sun went down and lasted for 3-4 hours. After an hour or so of wakefulness (more on this in a moment), people went back to sleep for another 3-4 hours. During this period of wakefulness between the first and second sleeps, evidence abounds that people did either what was necessary - chopped wood, prepared food, prayed and such - or what was enjoyable - read, talked with bedfellows, had sex and so on. According to Ekirch, the surprising point in his discoveries is not that this practice seems to have been almost entirely forgotten in the post-industrialised world, but that it was such a commonality - references abounding in plain sight - in the first place. In England, prior to, and even during, the early phases of the Industrial Revolution, records of first and second sleeps are abundant and exist without any attention being drawn to their being in any way unusual. That’s because, according to Ekirch, they weren’t. In 1840, Charles Dickens dropped a ‘casual’ mention into Barnaby Rudge, “He knew this, even in the horror with which he started from his first sleep, and threw up the window…” Ekirch opens his 2001 paper, Sleep We Have Lost: Pre-industrial Slumber in the British Isles, (out of which his book, At Day’s Close: Night in Times Past was developed), with journal notes made by the Scottish novelist Robert Louis Stevenson. These notes, written about his time spent camping and hiking through the Cévennes in France in 1878, describe with great poetry what he calls “the stirring hour” and “...this nightly resurrection” - that interval between sleeps which, even by Stevenson’s time, was largely a thing forgotten to history. It is a poignant opening to a piece of research that ‘rediscovered’ a practice which, to your ancestors, would almost certainly have been the norm. Robert Louis Stevenson takes his 'first sleep' in Cevannes WHY did we sleep twice? There have been suggestions that bi-phasal sleep became lodged in western Europe because of the requirements of early Christianity - monkish orders rising during the darkened hours to recite verses and pray - and that this embedded itself in European Catholicism which, in turn, promoted the same such nightly devotions from all strata of society. According to Ekirch, this can’t be the root of segmented sleep, because the very practice not only predates early Christianity, it existed across the world in areas which were, until relatively recently, untouched by Christian missionaries and religious conquistadors. Just why we took two sleeps at night is a complex question, linked perhaps to the dangers our ancestors (and not even to distant ones at that) faced by sleeping through the night - from predators to criminals. Night could be, it must be remembered, a terrifying time for all, dense as it might have been with frightful superstitions, religious paranoia, and the very real criminals that moved unseen. The night time was literally and metaphorically a time when the disreputable elements of life emerged: “Associations with night before the 17th Century were not good," he says. The night was a place populated by people of disrepute - criminals, prostitutes and drunks.” (Kolovsky, Craig.) Breaking sleep, as unnatural as it may seem to us now, could be fundamental to the survival of our ancestors. Sleep was a much more vulnerable state for our ancestors to have to endure than for most of us today. Unless the moon was visible at night, the darkness of the pre-industrial world would have been absolute. When people actually took to their beds for their first sleep was, in part, also related to the darkness because, as Professor Ekirch plainly stated in Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies:

“As in many preindustrial cultures, sleep onset depended less on a fixed timetable than on the existence of things to do.” Since pre industrial England relied so heavily on the daylight to accomplish these ‘things to do’ - our daily toils - once the night arrived it would have been near-impossible to conduct anything except the least arduous of tasks, such as talking, eating, or sleeping. If the work had been accomplished for the day - in the hours of light during which it was possible to accomplish it - then the timing of the ‘first sleep’ need not have been rigid. However, it cannot be overstated just how utterly devoid of light the night could become in a world before the Industrial Revolution. Unless the moon rendered otherwise, darkness would have been near absolute for anyone who could not afford artificial light - candles, oil lamps and such. And this is where the answer to the question of why we no longer have two sleeps at night is to be found: artificial light. Perhaps the more important question isn’t really why we used to have two sleeps and a ‘break’ but why we stopped the practice. The wealthier classes were perhaps the first to move away from the prehistoric ‘two sleep’ pattern because of their earlier access to artificial light - candles, oil lamps, wood fires etc. The Industrial Revolution forced the proliferation of light sources and the brightness of those sources across the British Isles. Gas lights - never really ubiquitous outside of major urban centres - nonetheless opened up the night to those who had hitherto retreated from it. Once the electric lightbulb, with its powerful luminescence and lower cost, changed the British night from dark to light, the practice of two sleeps quickly faded into obscurity. No more was it necessary to stop work when the sun went below the horizon; no longer was it necessary to fear the night and barricade oneself behind locked doors. In short, people began experiencing the night (for both work and leisure) and sleeping later - to the point where the first sleep became the only sleep. In a very short period of time indeed - perhaps as little as one hundred and fifty years - your ancestors went from a nocturnal pattern of sleep that had endured for millennia whereby we slept and then woke and then slept again, to a consolidated sleep determined primarily by the growth of artificial light. Your ancestors from almost certainly followed the practice of two sleeps. What is perhaps equally important is that, since England was the first country to industrialise, they were also probably the first to abandon the practice. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (Co-Editor of Versus History) @thelibrarian6 Bibliography Ekirch, A. Roger. Segmented Sleep in Preindustrial Societies. (http://www.history.vt.edu/Ekirch/sleep_39_03_715.pdf ) Ekirch, A. Roger. Sleep We Have Lost: Post-industrial Slumber in the British Isles (https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5f7d/10e30df23c62edc499ff26e909764e8946ad.pdf?_ga=2.82364371.494877159.1561369868-1007184158.1561369868) Koslofsky, Craig. Evening's Empire: A History of the Night in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge and New York Cambridge University Press 2011) |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed