|

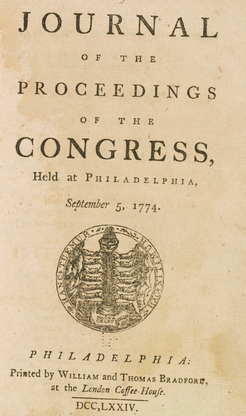

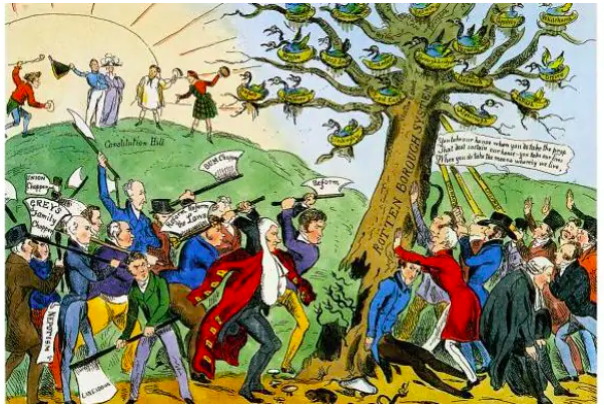

In the current UK political climate it is not uncommon to hear that democracy is under threat, with people of many different outlooks discussing the extent to which ‘the will of the people’ is being either adhered to or ignored. Implicit among all claims however is the idea that the United Kingdom has a rich history of democracy. This may be true in relation to some other countries, but it does not actually go back quite as far as one might think. The traditional starting point of British democracy is the signing of Magna Carta in 1215, a legal document that placed limits on the absolute power of the King. Magna Carta stated many things, establishing trial by jury as a right for all free men, giving liberties to the Church and London, but it also necessitated the consultation of a ‘Great Council’ by the monarch in their rule. This council was far from democratic, being made up only of the greatest magnates and power holders in the land. However, it did mark the end of the ‘absolute’ right to rule of English monarchs and denote that there would be some element of people power in the governance of England. The principles of Magna Carta have spread through much of the world, including to the North American continent. Indeed, if you look at the proceedings of the First Continental Congress of 1774, in some senses initiating the move away from British rule and to American Democracy, the title page contains an image of liberty adopted by the Congress with Magna Carta as its base. There is some irony here. In England, Magna Carta far from ushered in a representative democracy such as citizens on either side of the Atlantic would recognise today. We should not look back to Magna Carta as ushering in representative democracy. So then, what were the chances, even if we go back just a couple of hundred years of an average British person having the vote in a representative democracy? In short, unless they came from the upper echelons of society the chance that they had the vote until extremely recently (in historical terms) is very slim. Firstly we can categorically rule out half of brits having the vote solely on the basis of their sex. With the exception of a few anomalies such as the Isle of Man (ironically), Tuscany and Finland, women were not granted the right to vote until the end of WWI. Even the anomalies preceded the end of WWI by only a few decades and these are statistically so small as to be discounted. Yet the chances of a specific briton having the vote is little better. The first key date on which the answer to this question depends is 1832. The political system used within the British Isles, and the concomitant right to vote, was more or less the same from late medieval times until the so called ‘Great Reform Act’ of 1832. This was the first of a series of laws passed which expanded the number of people who could vote in England and Wales, with a similar law also passed in Scotland and Ireland (at that time under direct British rule). If your ancestors left the British Isles before 1832 they were highly unlikely to have had the vote under this unreformed system. In Scotland, the best estimate of people who were qualified voters is just 0.2%, with the MP for the capital of Edinburgh chosen by the votes of just 33 people! Things were slightly better in England with your male ancestors having a roughly 1 in 25 chance of qualifying to vote. A 4% chance may sound reasonable, even if the way in which one was qualified as eligible to vote was anything but. The country was a patchwork quilt of different systems. In the County constituencies (in effect rural areas), the qualification had been established in 1430, that to qualify as a voter one needed to own (and specifically not rent!) land worth a minimum of 40 shillings. In some counties such as Middlesex this could equate to just 0.22% of people having the vote. If one came from more urban areas, they would have lived within a borough constituency. The borough constituencies of England and Wales had no uniform qualification for voting and their size varied from the infamous Old Sarum, which was a ‘rotten’ borough with ‘no house nor vestige of a house’ yet it still returned two MPs, with the owners of certain sections of a field eligible to vote! Other constituencies, nicknamed pot-walloper boroughs, required that a man not claim poor relief and had a fireplace big enough to boil a certain size of pot! Additionally, if you were a member of the town council in a corporation borough, owner of a specific house in a burgage borough or a payer of poor relief in a scot and lot borough, then, in a rather convoluted manner you had the right to vote.

Sadly, even if they did have the right to vote, many british people were never given the chance to exercise their right. While there were elections at least every seven years, there was every chance that in a constituency there would be an uncontested election with only one candidate. In the 1831 elections, the last before these reforms, only one third of elections were contested (and even in 1910 25% went uncontested!). Matters did improve after 1832, though not very much. Estimates vary but the number of eligible voters jumped from about 4% to somewhere about 6%. Groundbreaking. Come the late 1860s and the passing of a Second Reform Act in 1867, the number of eligible voters jumped to somewhere in the region of 32% of males, with a further jump to nearly 60% after further reform in the mid 1880s. So there we have it, before 1832, an average Englishman had at best a 4% chance of having the right to vote (if they were male) and only a one in 3 chance (so 1.33% overall) of being able to use that, while any Scotsmen had an even lesser chance of doing so. It does make you wonder which history we're remembering at times.... Conal Smith @prohistoricman Bibliography Blackburn, R. The Electoral System in Britain Fisher, D. R. The House of Commons, 1820-1832, History of Parliament Trust, 2009, Vol III Houston, R. Scotland: A Very Short introduction

1 Comment

|

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed