|

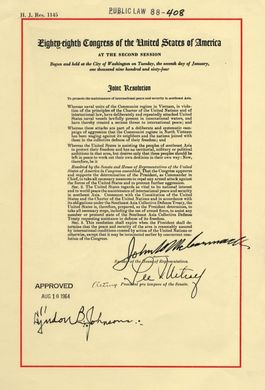

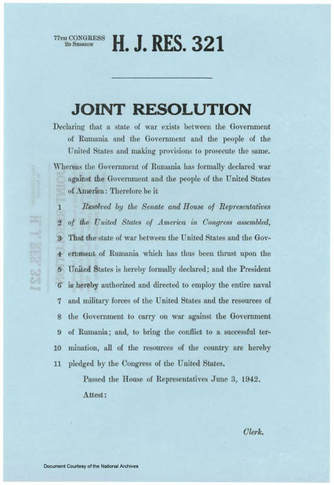

The ‘Tonkin Gulf Resolution’, August 10th, 1964 Our recent Versus History podcast was a fifteen-minute special in which Patrick asked me some quick-fire questions in the allotted time on one of my particular areas of interest. The area of interest that I elected to have questions fired at me upon was American involvement in the Vietnam War. For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by the Vietnam War. I am very much aware that the term ‘fascinated’ is perhaps wholly inappropriate a verb to employ when discussing an event in which countless numbers of people lost their lives, and one which still carries a present-day legacy of physical and emotional trauma, but it is, to me, the right word to use. It is entirely possible that my fascination was conceived during my early to mid-teens when I would spend school lunchtimes at a friend’s house watching (among a number of movies I wasn’t supposed to watch at such a tender age) the Oliver Stone film, Platoon. The horror of the conflict and the stark and complex differences between the ‘soldiers’ on both sides, as well as the differences between the American soldiers themselves, made for a jarring, unsettling viewing experience. The more I learned and, later, taught about American involvement in the Vietnam War, the more it became clear to me why it was so, enigmatic. Again, you may think this a terrible choice of adjective to describe an event of such tragedy and horror - and for the most part, you would be correct in your thinking, except that... Ask yourself this question: When did the Vietnam War begin? Go one further and ask yourself: When did American involvement in Vietnam begin? The enigma that I speak of is bound up in these two questions. It used to be that wars were a largely formal affair - war was declared, lines were drawn, sides were assembled, and battle commenced. The United States has not issued a formal declaration of war since June 4th 1942, which was against Rumania. Of course, to suggest that the United States has been entirely uninvolved in direct military conflict since 1942 would garner immediate incredulity. However, the fact still stands: the United States Congress (for it is only the legislature which can do so) has declared war ‘only’ eleven times in its history, starting in 1812 against the British, and ending in 1942 against the Rumanians. And therein lies the rub. As historians of conventional wars, we can place our finger on a date in a calendar, or a mark on a timeline and declare with the utmost of confidence, “Here, here is where the war starts!”. With the conflict in Vietnam, we can have no such confidence because we can do no such thing. US Declaration of War on Rumania, June 4th 1942 All of what we would call modern day Vietnam (as well as many of its surrounding neighbours - often referred to collectively as Indochina) had been colonised and ruled, almost without break, for hundreds of years by various foreign interlocutors - from China, to France, to Japan, back to France, and then - according to most Vietnamese - to the United States. Each subsequent incoming coloniser (for that is how they were most certainly viewed by the vast majority of the people of Vietnam) came into the country immediately upon the heels of the outgoing coloniser. In some cases, the outgoing invader was forced out by the incoming invader. In some cases, the invader was chased out by the Vietnamese themselves. In other cases - one of particular note - the outgoing occupier (a failing France) asked for assistance from someone they hoped would take on some of the burden of ruling Vietnam - the United States.

Since there is no declaration of war to which we can point as the ‘start’ of the war, then the language we employ must shift to accommodate the vagaries of a war without one. The term we generally use in our investigation is ‘involvement’. In many ways this word is a poor substitute for ‘beginning’ or ‘start’ - instead of making things clearer, the new semantic actually makes murkier the already murky water. Ask any Historian to determine the origin of a war, and expect a deep inhalation of breath before they begin. Ask any Historian about the origin of involvement in a war, and you had better tell your husband or wife that you’ll be late home for dinner. The reason? How do you quantify involvement? How do you qualify involvement? By what criteria do you judge involvement? What does involvement even mean? You know what I mean? Take a deep breath... Without a declaration of war, at what point would you consider America to be involved in Vietnam? If a president utters public phrases criticising French occupation of Vietnam, does that represent a public investment in the concerns of the country? If a president begins discussing who should rule Vietnam once World War Two is over and the Japanese are defeated, does this constitute American involvement? FDR did both of these things. If American soldiers, including Major Allison Thomas, as part of an OSS (Office of Strategic Services) mission had parachuted into North Vietnam to train Ho Chi Minh’s Viet Minh guerrillas to help prevent Japanese escape and gather intelligence, would this constitute American involvement in Vietnam? This happened in the dying days of World War Two, under President Truman. In order to guarantee French support in NATO, and to avoid a Cold War power vacuum being created by a French loss in Indochina (who were now fighting the Viet Minh), Truman authorised millions of dollars in financial and military assistance to the French. Would this be considered US military involvement in Vietnam? President Eisenhower gave billions of dollars worth of aid and provided 1500 military advisors to Diem (the leader of South Vietnam) who helped establish the ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam). He even guaranteed that he would support Diem if he chose not to hold the free elections that had been called for under the Geneva Accords of 1954. Would this be considered involvement? Remember, at this point in time - 1954 - there are no American ‘boots on the ground’. When the French lose at the Battle of Dienbienphu in 1954 and decide to leave Vietnam for good, America already has a financial, military and ideological commitment to the security of South Vietnam. And yet… no war. When JFK, in 1956, gives a speech determining that ‘Vietnam is the place”, is he foreshadowing an increased involvement? When Kennedy becomes the President and increases financial and military assistance, including helicopters and pilot ‘advisers’, authorises the use of Agent Orange and Napalm, increases the number of military ‘advisers’ to 16,000 by 1963, creates the MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam), secretly sends Green Berets, and authorises the Strategic Hamlets Programme, is America involved? Remember, there are still no official US soldiers fighting and there is no Congressionally recognised war. When President Johnson convinces Congress to pass, what was known as, the Tonkin Gulf Resolution, authorising presidential discretion in terms of a military response, is America involved? Is it involved at the point at which Operation Rolling Thunder begins, in 1965, bombing the jungles and villages of North Vietnam, dropping more ordinance than was dropped on Europe during the entirety of World War Two in the process? Is it involved when LBJ authorises an escalation of over half a million troops to assist the government of South Vietnam fight against the Vietcong and the Viet Minh? Exhausting, right? And remember, still no declaration of war by the US Congress. Thank you for bearing with me. Let me synthesise:

Where does this leave the student of American involvement in Vietnam? It leaves you with an interesting and unique opportunity: you get to choose both the meaning of the word ‘involvement’ and determine the point at which you consider the US to be involved. That’s what is so wonderful about the subject of History: provided you maintain an honest commitment to the evidence, you get to set the parameters of your investigation. Dr. Elliott L. Watson (@thelibrarian6) Co- Editor, Versus History

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed