|

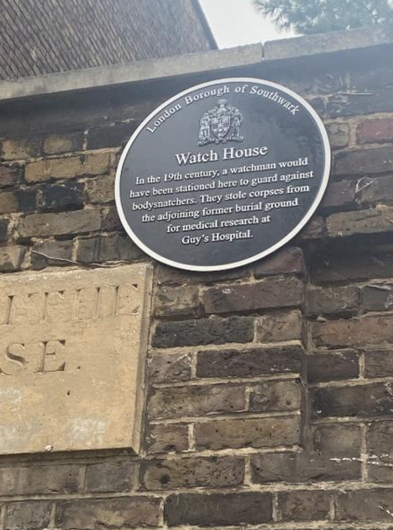

During the early 19th century grave robbery became common practice due to the increased interest in medical science creating a demand amongst medical students for bodies to conduct medical research.

As historian Sarah Wise notes in her extensive study of the subject The Italian Boy in 1831 there were estimated to be around 800 medical students in London, Up until 1832 the only source of these bodies for medical studies were those of criminals hanged for murder. The number of bodies available to the students was far too low to accommodate their demand. Resurrection gangs were highly organised tight knit operators, networking in specific meeting places within travelling distance of medical schools, such as at the Bricklayers Arms public house on the Old Kent Road. For historians, how those caught in the act of grave robbery were dealt with by the courts sheds light on tensions between Victorian ‘laissez-faire’ economics and public morality. Resurrectionist gangs were despised amongst the general population, families of the deceased were left without closure, as their loved ones were taken and used without their consent. Additionally, the practice was dangerous as grave robbers often encountered angry mobs and were at risk of being caught and punished. Members of resurrectionist gangs would often scatter body parts around the homes of rival gangs to draw attention to them and arouse public hostility. However, despite this widespread public disdain, penal sentences for grave robbers were relatively light. In the eyes of the law, the dead human body did not belong to anyone and was not considered to be of material value. The maximum penalty was a fine or six months imprisonment. Cases were most likely to be tried as misdemeanours in a magistrate’s court and as a result very few records of court proceedings involving body snatching remain on public record. Resurrectionist gangs were careful not to take anything else from the grave to avoid more serious charges. In response to the growing problem of grave robbery, the Anatomy Act of 1832 was passed in the UK. The act allowed for the legal donation of bodies to medical schools and abolished the practice of using executed criminals as the only legal source of cadavers. It also allowed for the bodies of those who had died in workhouses to be used. While this put grave robbers out of business, disposing of the bodies of the poor in the same way as bodies of the hanged served to stigmatise poverty by equating the bodies of deceased paupers with the dead bodies of criminals in the public mind. Architectural historian, Professor James Stevens Curl’s research reveals that even though the business of grave robbery effectively ended in 1832 with the change in regulation, the repetition and fear surrounding the activities of the resurrectionist gangs lived on. Many families held onto corpses of relatives in their houses until they had decayed too far to be of interest to any anatomist. Furthermore for the multitude of the working population living on incomes just above workhouse poverty levels, a family bereavement posed serious economic difficulties. This also meant sanitary disposal of bodies would often have to be delayed until the bereaved raised the funds for a funeral. In conclusion the study of resurrection gangs and their activities can help historians shed light on changing Victorian attitudes towards death and memorial. The demand for cadavers for medical research led to the desecration of graves and the violation of the rights of the deceased and their families. While the Anatomy Act of 1832 helped to address the problem, it did not eliminate it. Further Reading Curl, J.S. (2004) The Victorian celebration of death. Stroud (Gloucester, England): Sutton. Wise, S. (2012) The Italian boy: Murder and grave-robbery in 1830s London. London: Vintage Digital. Written by Versus History Guest History Blogger Karl Brown (@MrBuddwing65). You can follow Karl on Twitter here.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed