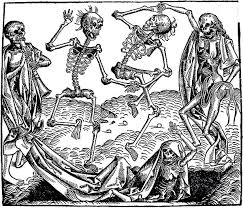

...the black death was actually a good thingIf you know anything about the Black Death, it is most likely that it was a horrible disease that killed huge numbers of people right across Europe a long time ago. This is certainly true, but did you know that (so long as you escaped the illness) it actually hugely improved life for most people in Britain? In the year 1348 a terrible condition began to strike people in England and rampaged through the nation for the next four years. A contemporary description by Giovanni Boccaccio gives us a graphic view of the horrors of the disease which “began both in men and women with certain swellings in the groin or under the armpit. They grew to the size of a small apple or an egg, more or less, and were vulgarly called tumours. In a short space of time these tumours spread from the two parts named all over the body. Soon after this the symptoms changed and black or purple spots appeared on the arms or thighs or any other part of the body, sometimes a few large ones, sometimes many little ones. These spots were a certain sign of death, just as the original tumour had been and still remained” To catch the disease was clearly extremely painful and unpleasant, but also fatal in most cases. Estimates of the casualty rate in England range from one third of the population to roughly half. On a national level it was a disaster. This was perhaps most obvious for those who caught the disease. However, with such a high mortality rate everybody would have close family and friends struck down and been affected in the most harrowing way. Yet, the survivors of the disease actually found their lives materially improved in the second half of the fourteenth century. With such a high proportion of the population removed, and therefore the available pool of labour shrunk radically, peasants, as the majority of the population were, found themselves in demand. Statistical data is inevitably patchy, but the laws passed by the government in the wake of the Black Death reveal the increased value in peasants’ labour.

The Ordinance of Labourers, a law of 1349, stated that when hiring workers “no man pay, or promise to pay, any servant any more wages, liveries, meed, or salary than was wont, as afore” (before the plague) As well as attempting to freeze wages the Ordinance also placed a price freeze on staple foodstuffs such as meat, fish and bread as well as the price that could be charged by skilled craftsmen such as smiths. Fortunately for the labourers of England, evidence suggests this law was unsuccessful. It was followed up by another legal attempt to restrain prices in 1351 called the Statute of Labourers, but neither of these seem to have had a large impact; as many economists will tell you, market forces can be hard to control. In his seminal work Making a Living in the Middle Ages, Chris Dyer states that “the rise in wages was at first modest, and striking improvement often came in the last quarter of the fourteenth century”. So there it is. If you were an agricultural labourer, as most Englishmen were, and you survived the Black Death, you could gain a little more coin for your hard labours and perhaps find it a little easier to put food on the table for yourself and your family.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed