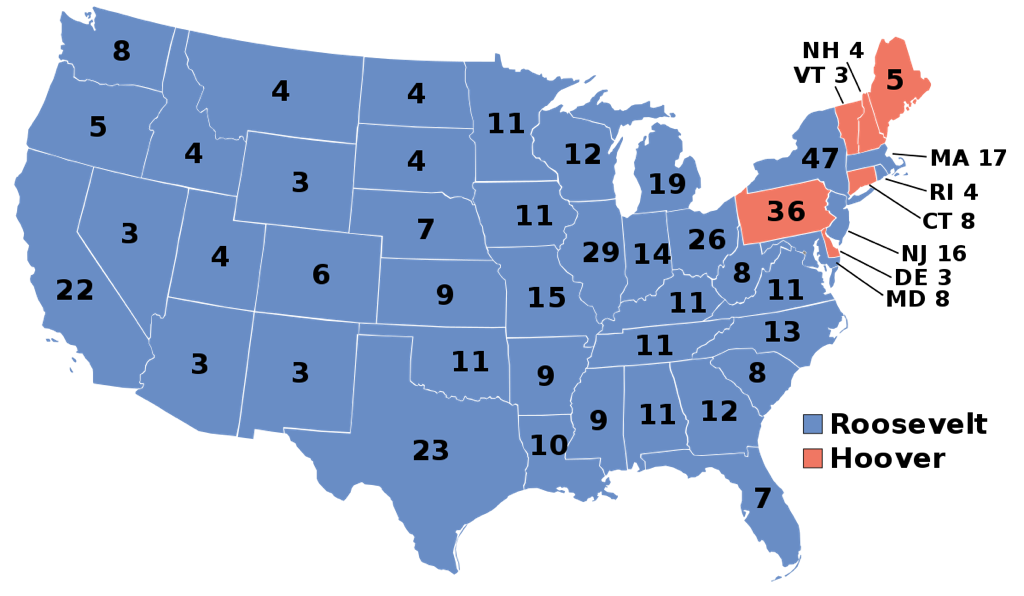

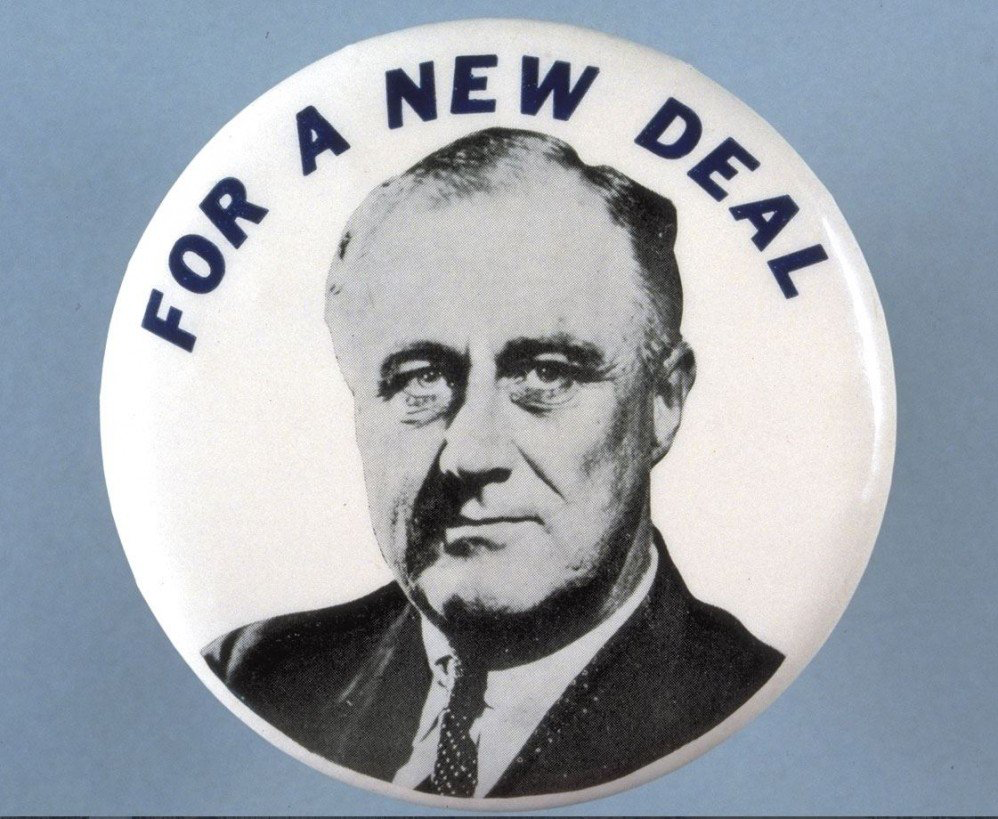

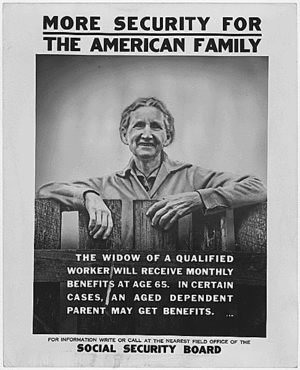

The New Deal: Three lessons on the malleability of significanceStudents of history are often charged with determining the significance of events, issues and people. The New Deal offers a wonderful opportunity to delve into the many ways that significance can be determined, assessed, and deployed. In March 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took control of the White House from Herbert Hoover. FDR was a man born into a wealthy New York family and was as close to an aristocrat as you were likely to come across in interwar America. He held public office almost unceasingly from 1910 (when he became the Senator for New York) until his death in 1945 whilst serving as President. Hoover was a self-made man, beginning his career as an engineer and developing himself into a very successful businessman. He entered public office as the head of the US Food Administration during the First World War, creating a name for himself as a global humanitarian. As Secretary for Commerce during the 1920’s, Hoover was known for his dedication, professionalism and efficiency. A Republican, he served as the 31st President of the United States from 1928 until his humiliating defeat to the Democrat, Roosevelt, in 1932. Rarely has there been a US presidential election that so starkly illustrated the differences between the modern incarnations of the Republican and Democratic Parties. For the majority of the 1920’s, the central tenets of Republicanism - ‘Rugged Individualism’, a laissez faire approach to economic growth, a fervent (near hysterical) aversion to socialism, and an unwavering belief in the robustness of the American Dream - dominated the economic, social, and political landscape. Three successive Republican presidents, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and then Herbert Hoover, presided over an America that appeared (at least on the surface) to be immune to the normal boom-bust cycles of economic theatre. In fact, in a campaign speech in 1928, Hoover stated that, “We in America today are nearer to the final triumph over poverty than ever before in the history of any land”. In less than a year, the US stock market crashed and the country entered a period of sustained economic collapse. Roosevelt, a man who, over a decade earlier, had expressed a desire to see Hoover become president, stood against many of the principles upon which Hoover and the Republican establishment - so long the saviours of America after the upheaval of the Great War - had based their policies. In his campaign, FDR had offered the American people a ‘New Deal’. What this ‘New Deal’ constituted was kept deliberately vague, but it promised something that Hoover and his fellow Republicans (who had naturally borne the brunt of public dissatisfaction over the problems associated with the Great Depression) seemed incapable of demonstrating: action. In his inaugural address on the 4th March 1932, FDR said the following: “This Nation asks for action, and action now”. Whatever the reality of the promises he made and the solutions that he proffered in the build up to the election, the American public bought into them. He beat Hoover in the presidential election of 1932 with 472 Electoral College votes to Hoover’s 59. FDR took around 60% of the popular vote. The following are three lessons that I have learned through my study of FDR and the New Deal. The following are three lessons that I have learned through my study of FDR and the New Deal. The Semantic Lesson: What’s in a name? FDR and his writers were familiar with, and understood the value of, the post-war print and radio media. Although he was prolific in his campaign movements around the country, personal appearances at rallies would always be restricted by his polio, the size of the US, and the challenges associated with criss-crossing it. The ‘New Deal’ was crafted as a slogan before it ever became a set of principles and policies and it was designed to encapsulate all that Roosevelt offered and all that differentiated him from Hoover and the Republicans. Economist, social theorist, semanticist and advisor to Roosevelt, Stuart Chase created the modern manifestation of ‘A New Deal’ (although in purely literary terms it belongs to Mark Twain) and essentially offered it to FDR as a piece of semantic perfection that would resonate with the electorate without denoting specific policy stipulations. Anything ‘New’ meant change and any change meant difference. Any difference meant the opposite of what had come before. The opposite of what had come before could only be better than what had happened, and was continuing to happen in America. In 1932, there were roughly 18 million Americans unemployed (nearly a quarter of those men and women employable). By the end of 1932, most banks were closed or had gone bankrupt. GDP had collapsed to less than half of what it had been before the Wall Street Crash. Whatever it meant in truth, to the electorate it was clear that ‘New’ was a good thing. The Republicans had spent over a decade reinforcing the truism that an administration’s approach to governance was only successful when that governance was ‘hands off’. Success in all walks of life was due to individual hard work and a steadfast belief in an unregulated private sector. Consequently, when the country went to Hell in a handbasket, the people of America lost faith in those principles of Republicanism which had, for so long, trumpeted self-help over community assistance, as well as government non-intervention. Hoover was labeled (quite incorrectly, in many respects) a ‘do nothing president’, at a time when the people of America were desperate for help. FDR’s New Deal offered that help. In fact, it offered them a ‘deal’ - a partnership. No longer would Americans feel ‘forgotten’ in their time of need. US citizens would no longer feel alone and abandoned because Roosevelt and his administration were ‘in it with them’. Their problems were his problems, and vice versa. Perhaps for the first time in US history, the government du jour would cease to be a remote and unsympathetic entity, it would be an equal partner with, and have an equal investment in, the success and wellbeing of its citizens. One (the government) would be indistinguishable from the other (the citizens). A Deal’s a Deal. Particularly a New one. The Political Lesson: The difference between success and failure depends upon your vantage point In the most recent New York Times rankings of ‘Presidential Greatness’ - a poll with a variety of metrics and revisited every four years - Franklin Delano Roosevelt ranks third behind Abraham Lincoln (1st) and George Washington (2nd). Among Democratic, Republican and Independent scholars, his position is unmoved and has remained that way for almost as long as the poll has been going. And yet, and yet... FDR did not end the problems associated with the Great Depression - he didn’t even come close. So, how is it that we can judge FDR as worthy of such historical praise, even though it is summarily accepted that the Great Depression evaporated almost as soon World War Two began, rather than because of the impact of the New Deal? The answer (in addition to everything else contained in this post) is simpler than you might imagine: there are always different interpretations of ‘success and failure’. A simple example might be: unemployment during the early days of the Great Depression reached 18 million; by 1939 it was 9 million. A critic would judge 9 million people as an extraordinary number of Americans still unemployed - and thus cite the New Deal as a failure in its ‘primary task’: that of putting people back to work. Others, including FDR himself, would take the same evidence and, using a different vantage point, would turn the same statistic on its head, arguing that the New Deal was able to cut unemployment by 50% in 6 years. Perhaps another example, should one desire to have another, might be that whereas many countries in Europe began turning to extremist politics for solutions to the economic damage wrought by the worldwide depression - the obvious being the fascist risings in Germany, Italy, and Spain and the tide of communist support pushing into mainstream politics - the United States was never troubled by any such dangers. Even in the UK - the supposed bastion of even-tempered, long suffering souls, Oswald Mosley gained tremendous support for his Hitlerian-style aspirations. Is it fair or right to say that the New Deal was responsible for maintaining America’s resolute adherence to democracy and capitalism? Maybe, maybe not. It depends upon your vantage point. The Historical Lesson: Precedent is often more important than achievement As we have just read, the Great Depression and its associated problems still continued, for the most part, unabated until the outbreak of World War Two. If the New Deal did not kill the Depression, then why discuss it at all in terms of achievement? Franklin Delano Roosevelt won an unprecedented four presidential elections and there is no reason to think that, had he survived, he would not have won a fifth. The 22nd Amendment to the US Constitution, ratified in 1951, put restrictions on those looking to hold the office of the presidency, stating that “No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice”. This was, without doubt, a response to the tenure of FDR. Though many precedents were set by the 32nd president that were to be followed by others, his four term presidency was not one of them. Precedent 1: Regulating stock brokers can often be like taking candy from a baby - they may cry, but it’s good for them to understand that overindulgence can lead to problems later. Prior to the New Deal, regulation of the Stock Market was seen as unnecessary, unwelcome, and dangerous. Consequently, activities that we would consider crimes today (and in truth were crimes that went unpunished then - so called ‘blue sky laws’ were ignored en masse) such as insider trading, manipulating markets, cartels and such, were overlooked and, in fact, often actively encouraged because of the government’s ideological commitment to deregulation. However, after the crash of 1929, many in government (even some Republicans) saw that the stock market required some form of federal control. The Securities Exchange Act of 1934, passed to enforce the Securities Act of 1933, created the Securities and Exchange Commission - more commonly known as the SEC - which was designed specifically to tackle the corruption and lack of transparency of the US Stock Market. The SEC did much to restore/instill public faith in the way the American stock market would operate and helped to stabilise, in relative terms, Wall Street. However, the achievement of the SEC, bearing in mind its first chief was Joe Kennedy - the wildly successful financial malepractor and prolific breaker of banking laws -, is its existential longevity as well as its value as a precedent that would be followed by governments across the world. The SEC continues to regulate Wall Street to this day and well over half of the world’s countries have their own version. Precedent 2: Government intervention isn’t always a bad thing Despite the emergence of the progressive parties and politicians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the American people still remained, until 1933, a people encouraged (if not downright forced) to fend for themselves. The principles of ‘Rugged Individualism’ had dominated North American life for centuries (the products of which were embedded as thoroughly in the political landscape as they were in the physical) but they had recently come to represent the inadequacies of three Republican administrations. As a result, Roosevelt decided early in his presidential campaign that his government needed to look out for the ‘forgotten man’ of America. Hoover once said that “If a man has not made a million by the age of 40, he is not worth much”; FDR, on the other hand, said that government plans must ‘...build from the bottom up and not from the top down, that put their faith once more in the forgotten man at the bottom of the economic pyramid”. Roosevelt’s New Deal may very well have failed to rescue the country from the deeper-set problems of the Great Depression, but one thing it did achieve was a general acknowledgement from many within the political establishment, and a keen expectation from many Americans, that government needed to do more to protect its citizens from hardship. It was no longer sufficient for government to create an environment conducive to prosperity, it also needed to provide a safety net for those who were either unable to take advantage of that environment or those who suffered when that environment evaporated. As it did in 1929. Perhaps the greatest example of the New Deal’s paradigm shift towards the social and economic wellbeing of its citizens can be found in the Social Security Act of 1935. This remarkable piece of legislation introduced federal funding for old age pensions, child welfare, public health, people with disabilities, and unemployment insurance. In this, as well as other New Deal laws, were distilled the essence of the New Deal, and this essence - although not always successful - projected into the future of America. Perhaps ‘Obamacare’ is one of the most recent examples predicated upon the precedent established by the New Deal. Precedent 3: Presidents must be seen to be doing something While there is no doubt that Roosevelt was indeed a man of action - his first one hundred days in office were busier in terms of federal and executive action than any that had gone before and possibly after (regardless of President Trump’s assertions) - there is also no doubt that Herbert Hoover worked himself to exhaustion trying to solve the problems of the Depression. However, while there were clear ideological differences between the two men, and these certainly contributed to the outcome of the 1932 election, one of the more immediately recognisable differences (to the detriment of Hoover) was the ‘media savvy’ that one demonstrated and the other catastrophically failed to understand. No matter how hard a president actually works, he must be seen to be working. Hoover never understood the value of appearance - this is why he was labeled the ‘do nothing president’; FDR embraced the media and was, perhaps, the first of the ‘modern’ presidents, inasmuch as he he understood the importance of appearance as well as reality. Different historians characterise FDR’s relationship with the media using different adjectives: Graham J. White saw in Roosevelt a ‘virtuosity’ in his handling of a press that could not “...cease to admire” him; Leo Rosten, however, believed FDR was more cynical, turning his media charm on and off like a ‘faucet’. None, however, doubt that his relationship with the media was significant in the life of the New Deal. From his 998 press conferences during which crowds of reporters swamped his desk and freely asked their questions - unprecedented in the access they were afforded to the president -, to the famous ‘fireside chats’, whereby the reassuring actions of his government and the optimistic expectations he had of the American people, would be laid out in 31 radio addresses across his four terms, FDR was unlike any other president before him. Even those Americans who were unimpressed by either his policies or the ideology that underpinned them, could not fail to admire the image that he had created for himself through the media - as an energetic and active workman. This cultivated image (warranted or otherwise) is made all the more impressive when we remember that he was confined to a wheelchair for the duration of his presidency. How many photographs have you seen in contemporary newspapers of FDR in his wheelchair? I’ll wager good money that the number is low. With the advent of television and then social media, the importance of presidential appearance has become almost as important as the work done by the president. There is a strong case to be made that Roosevelt created this Presidency of Appearance. Dr Elliott L. Watson

Co Editor of Versus History

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed