|

When Versus History kindly asked me to submit a blog post I immediately thought about the threat of revolution in Britain from 1789-1848. This period has fascinated me since my undergraduate days and now I run a course on the subject for the WEA. Sadly, I don’t have the space to cover the entire sixty-year era here. The good news is I can focus instead on the story and some of the historiography of what is possibly the most interesting period, one when revolution seemed possible but did not happen: the “heroic age of popular radicalism” (E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, 1963) from 1816-20.

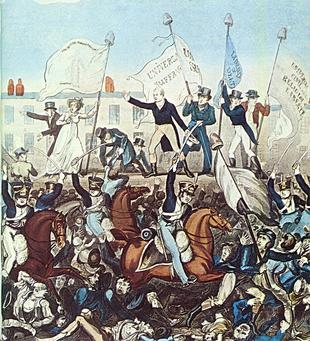

This five-year period includes a public campaign for parliamentary reform running parallel with risings in obscure northern villages (inspired, depending on who you believe, either by government agents or a revolutionary underground), attacks on demonstrations, legislation banning public meetings, and alleged coups d’état culminating in treason trials. The key question arising from all this drama relates directly to the credibility of the revolutionary threat: was it merely the invention of enterprising government agents, or did a revolutionary danger actually exist? Thompson’s The Making suggested the existence of an underground radical thread linking the British Jacobins of the 1790s to 1820. This tradition was harboured and nurtured in the manufacturing districts of the North, finding expression first in clandestine movements of the 1790s, then merging with trades unions via the Combination Acts. After a brief lull came the Luddites, and then finally the widespread campaign for parliamentary reform following the Napoleonic Wars - a campaign which involved open public agitation and covert revolutionary activity. The thread died with the Cato Street Conspiracy of 1820, the last of the proposed Jacobin coups d’etat (the first was in 1803, the “Despard Plot”, the second in 1816 at Spa Fields in London). Ten years later, Thomis and Holt’s Threats of Revolution in Britain 1789-1848 (1972) was in little doubt about the nature of any threat: “The revolutionary underground… seems to have been almost the determined creation of stubborn, short-sighted governments”. This is a view which has its origins in the aftermath of the 1817 Pentrich Rising, when the Leeds Mercury exposed a government spy (“Oliver the Spy”) said to have been responsible for inciting rebellion across the North. Fabian historiography of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries would find much to commend in the story of a ruthless administration sending agents provocateurs to poison the minds of sensible sober Englishmen. Three years later there were echoes of Oliver in the activities of another spy, George Edwards, during the Cato Street Conspiracy. So, amongst other concerns, Thompson’s critics had responded by citing government use of spies to encourage rebellion – allowing them to portray any discontent as the work of isolated, misguided and easily manipulated fools. And there the debate seemed to solidify into two competing and immovable sides. That is, until Edward Royle’s Revolutionary Britannia: Reflections on the threat of revolution in Britain, 1789 – 1848 (2000). Anybody interested in the years 1816 – 20 must read this book. Bringing new and old research together for the first time, Royle shows how a Thompsonian thread could be visible in the stories of men who claimed to have associations with revolutionary activity and in some cases were arrested and tried. Particularly illuminating is the case of John Blackwell, who led an attack on a Sheffield armoury in 1812. Blackwell reappeared four years later during a riot in Sheffield, the day after the alleged Spa Fields coup d’etat attempt in London. And then he put in a final appearance in April 1820 at the head of a crowd attempting to attack a Sheffield barracks on the same day as a rising in South Yorkshire was due to take place. As Royle asks, when considering the nature of the revolutionary threat from 1816-20: “Were ministers rather better informed than sceptical historians have sometimes liked to think?” Mike Towers (@Mike_Towers) Guest Versus History Blogger

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed