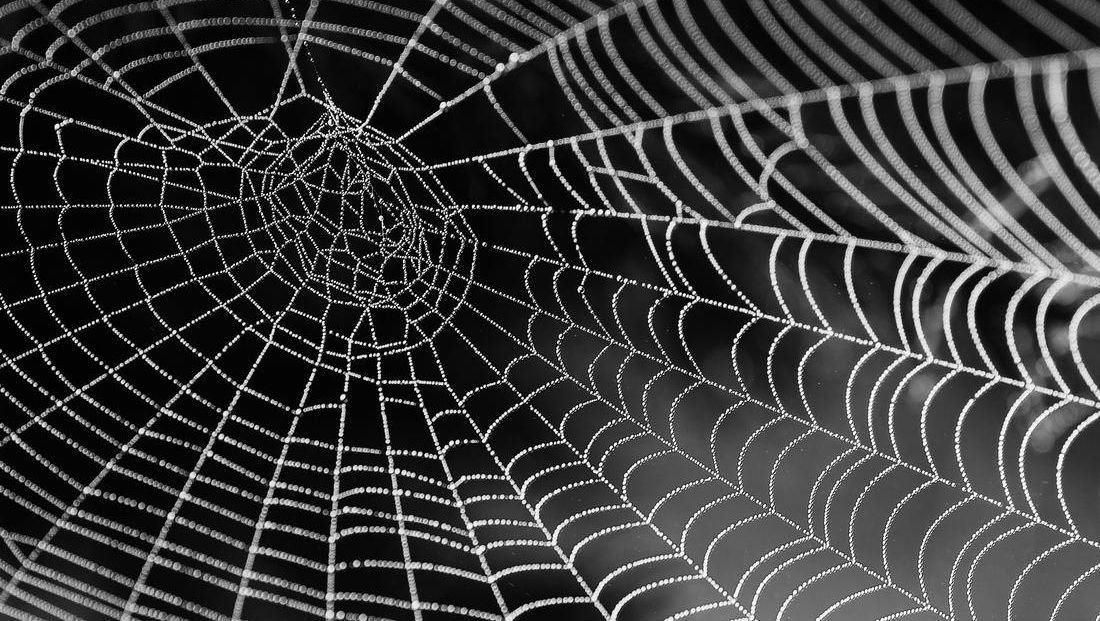

The Causal Web Here at Versus History, we spend a long time emphasising the symbiotic roles of cause and consequence in the creation of history: consequences require causes and thus causes can’t, by definition, exist without consequences. Something of a basic, but watertight piece of cyclical, deductive reasoning. Since the path of history is beset on all sides by the perils of determining cause and consequence, I thought I’d write a few of my thoughts down. In a number of our podcasts, as well as a few chapters of our new publication – 33 Easy Ways to Improve Your History Essays – Patrick and I have discussed the importance of moving beyond simple description or explanation of causes and consequences, towards a more evaluative analysis. What we mean by this is simple: we want our students to create, what Richard Evans calls in his book, In Defence of History, a ‘hierarchy of causes’. I think it is safe to say that history is never mono-causal but multi-causal. As a result, it is vital when answering a question linked to cause that students determine a series of causes to be explored. What’s more, they must, and this is crucial, also determine a hierarchical framework within which to set these causes; a framework constructed by answering the following question: Which cause is the most significant in relation to the others and why? Additionally, though they may judge one cause more important than the other (by virtue of causal relativism and the assigning of historical ‘value’), the student must also admit that there is a web of causes that it may be impossible to separate. Since it can only be the time-traveller who is able to return to a time period and cancel a cause – removing it from history – we can never honestly imagine a set of perfectly separate causes because we can never truly suppose what might have happened had one of the many causes never existed. Thus it is the responsibility of the history student to determine the key causes and then to assess their significance in relation to one another. Identifying the key causes carries an implicit judgement: that ALL of the causes which have been selected are important in some respect or another. This assessment is of profound significance because it is a powerful acknowledgement that, while one cause may be fundamentally more important than the rest (however that may be adjudged to be true), it is also true that every cause under discussion must also retain value – otherwise why discuss it at all? And so, it is imperative that all students of history determine a hierarchy of causation (and consequence) when writing history, but it is prudent to also acknowledge that a web of causes (and consequences), impossible to untangle, exists and that this web may even supersede the importance of any one cause. Best wishes, Elliott L. Watson (@thelibrarian6) #VersusHistory

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed