|

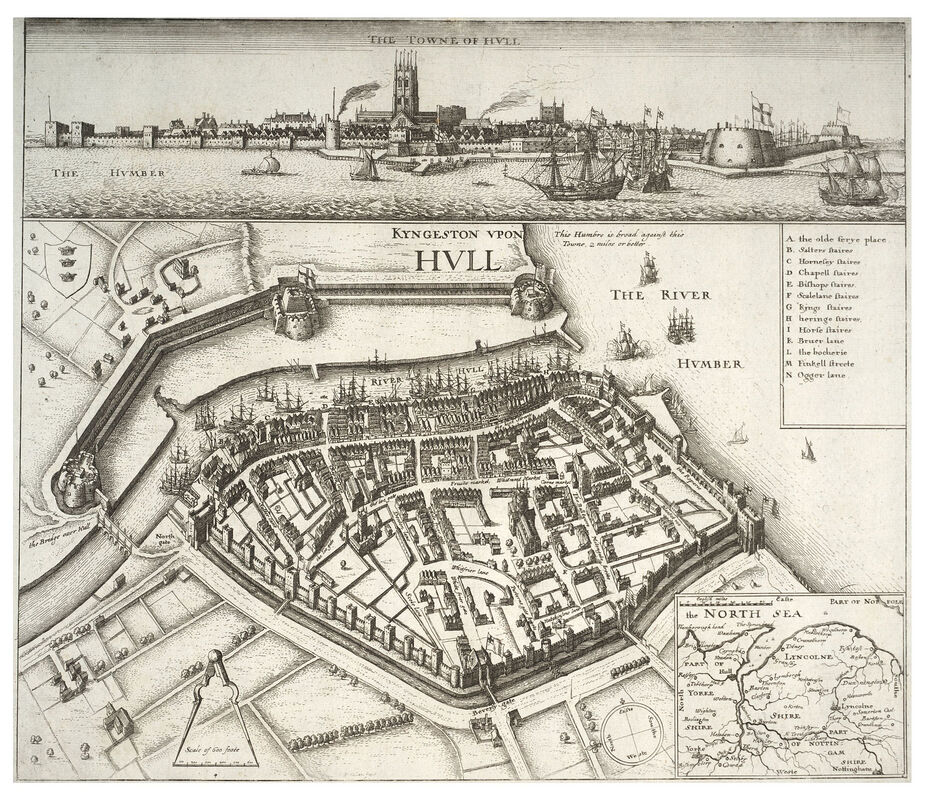

The English Civil War, fought between King Charles I and his Parliament, throw up many a strange story. One among them concerns the Hotham family. Parliamentarians, their loyalty was not always reliable, and Oliver Cromwell himself lost patience. On 1 January 1645, Captain John Hotham, having played loose with his loyalties in the wars that engulfed all three kingdoms of Britain, faced his end at the Tower of London. His proposal to pay Parliament £10,000 to commute his sentence to banishment had been declined, therefore supportively flanked by his brothers, he was put to death by the severing of his head from his body. The following day his father, Sir John, followed him to the block. In the months prior to the outbreak of civil war in England, the momentous actions of father and son delivered a port full of munitions to the parliamentarian cause. They went head-to-head with the king himself; an action that should have seen the Hotham’s wedded to Parliament for ever more. But within one year, that union became strained, for the Hotham’s loved their own status and standing more than either faction. The proud family rapidly fell from the grand pedestal upon which they had perched and managed to end up being mistrusted by both King Charles and Parliament. More especially, they incurred the wrath of Oliver Cromwell. 381 years ago, in January 1642, Parliament ordered Sir John Hotham to take control of Hull. Accordingly, his son led some troops to the town and then seized it – though this action was not borne from pure conviction to Parliament’s cause. Sir John, a one-time Governor of hull, had been dismissed from that post by the king in 1639. The spurned Hothams had coveted the return of this position ever since. Parliament, for their part, needed the town and its vital magazine and both parties became uneasy bedfellows. One of the strongest fortress towns in England was thus delivered to Parliament, along with an arsenal of weapons for 20,000 men, 7000 barrels of gunpowder and 120 pieces of ordnance. In gratitude to Sir John, Parliament appointed him Governor of Hull, a role that would bring infamy. Three months later, on 22 April 1642, Sir John received two surprise visitors; the king’s son, the 9-year-old Duke of York, and his nephew, the Elector Palatine. He reluctantly admitted them into the town. The next day – Saint George’s Day – Sir John’s own chivalry was tested when word reached him that King Charles I was now on his way. It was to be an epic showdown. Hull wasn’t big enough for both the king and Governor Hotham, and when His Majesty arrived, he found the gates already closed. As Sir John stood on the walls looking down upon the royal party, both his allegiance and that of Parliament were put to the ultimate test. This was personal. Parliament’s profession that it was opposing the king’s ‘evil counsellors’ and not the king himself, was cast into doubt. King Charles demanded entry. Hotham apologetically refused. Hull’s outer ditch, angled bastions, earthworks and the 25 towers atop its mediaeval walls seemed to reinforce this decision. The rasps of a royal trumpeter pronounced Hotham a traitor and some of the king’s men called out for the townsfolk to throw the governor from the walls. But nobody moved. Check-mated, the humiliated king finally withdrew. He wrote to Parliament demanding that justice be ‘exemplarily inflicted’ upon Sir John and specifically found it unforgiveable that Hotham delayed releasing his son and nephew until after further negotiation. Nearly four centuries later, this momentous event is regularly given as the unofficial start of the civil war in England. A further unexpected visitor arrived in June 1642, when a small ketch was captured, and a supposedly seasick Frenchman taken into custody at Hull. When brought before Sir John, the prisoner turned out to be none other than the king’s meddler-in-chief, Lord George Digby. The hapless Digby, with his golden locks and silver tongue, managed to secure a tacit agreement from Sir John to hand over Hull to the king. For the preservation of the governor’s honour, the monarch was to come in person and besiege the town. But Parliament’s suspicions were soon aroused, and the iron-willed Sir John Meldrum was posted to Hull to bolster Hotham’s backbone. Therefore, when the royal army did appear, digging trenches, flooding fields and raising batteries, the town remained defiant, and the king withdrew empty handed for a second time. Despite their expectations for preferment with Parliament, the wealthy and influential Hotham dominance of the region was rivalled by another Parliamentarian duo; that of Lord Fairfax and his son, Sir Thomas. It was Lord Fairfax who secured Parliament’s commission as commander in Yorkshire, but it would take more than a slip of paper to bring the Hothams into line, and they constantly disobeyed Fairfax to the detriment of the cause. The Hothams were not happy playing second fiddle to anyone on their home ground. By December 1642, young Captain Hotham was spilling his guts in letter after letter to the king’s northern general, the Earl of Newcastle. When Queen Henrietta Maria landed at Bridlington in February 1643, the captain met her on the pretext of arranging an exchange of prisoners. The Hothams did little to prevent the Queen’s march to York, along with the stash of arms, ammunition and money she’d gathered for her husband’s cause. Captain Hotham, in one of his indiscreet letters to Lord Newcastle, instead ventured that he had been so badly treated by Parliament that ‘no man can think my honour or honesty is further engaged to serve them’. Though in another he wrote of the violent and ill-conditioned officers in the king’s army and judged that he could not serve under any of them should he defect. By mid 1643, Captain Hotham’s indiscretions had made him many enemies; from John Hutchinson (Governor of Nottingham) to Oliver Cromwell, with whom the Hothams had also refused to co-operate militarily. As such, suspicions became ever more heightened. On 18 June 1643, Hutchinson finally arrested the younger Hotham. The captain fired off a letter to the queen, inviting her to rescue him, but promptly managed to escape and fled to Lincoln. He was recaptured soon enough and sent to London. During his time at Hull, Sir John Hotham had spoken out against Oliver Cromwell’s promotion of common men to officer rank. The headstrong Hotham had even threatened to fire on Cromwell’s men if they strayed into his territory. He’d also disobeyed Parliament’s Yorkshire commander, Lord Fairfax, causing a complaint to be lodged. Despite all of this, the one person who had steadfastly supported Sir John was Parliament’s Lord General, the Earl of Essex. But with his son imprisoned, time ran out for Sir John. He was forced to flee Hull, being fired at by his own garrison as he left. After being captured by his own cousin and then attempting an escape, it was said that he was clubbed from his horse by a musketeer and left with a black eye. When brought to the bar of the House of Commons to account for his actions, Sir John fell to tears. A trial was unavoidable. He found himself once again ensconced within a parliamentarian fortress; this time, however, it was the Tower of London. There both father and son languished. Four months passed. In October 1643, Lord General Essex intervened. He recommended that some of his officers try Sir John, but Parliament refused, instead desiring a full court martial. Essex then attempted to set the date of the trial as 8 December 1643, but he was again overruled. Nothing more was done for six months, and Sir John used his time in the Tower to pen a defence of his actions. Parliament granted him an allowance of five pounds per week, along with three pounds for his son, all paid from his estates; pocket money, which they must have found particularly galling. Sir John’s father-in-law unsuccessfully petitioned Parliament in June 1644, calling either for his trial or release. As the tide of war turned, so did the Hothams’ fortunes. Following the Battle of Marston Moor, 2 July 1644, royalist correspondence was captured which proved the Hothams had been in contact with the royalists. This was precisely what Parliament had been waiting for. The trial of father and son now proceeded apace, chaired by Sir William Waller. Sir John asked to sit during proceedings on account of being lame – his defence was quickly judged to be equally so. The argument that he only negotiated with the royalist Earl of Newcastle to buy time for Hull was dubious. He persisted, claiming that this was a tactic employed in the Thirty Years War, of which he was a veteran. The behaviour of father and son had doomed them. At this time, Lord General Essex’s influence was also on the wane, and he would soon be forced to step down. A new order was being ushered in; one which had no truck with the Hothams. Lord Ferdinando Fairfax, Sir John’s rival, was given the Hotham’s money, plate and goods. It was at this juncture that Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell steooed forward to extract his vengeance. Professor Ronal Hutton recently wrote that Cromwell was not to be sated in his pursuit of personal opponents within his own side, including the Hothams, who would be hounded to their deaths. Certainly, the House of Commons’ records bear this out. On 11 December 1644, Lady Hotham’s petition for clemency was reluctantly dismissed by a wavering House of Lords. It was, after all, a period where many moderate peers and MP’s felt threatened by the emerging dominance of men such as Oliver Cromwell. The Hothams fates seemed indicative of the factional infighting that had broken out at the heart of Parliament. On 14 December 1644, Sir John successfully petitioned Parliament for an extension of his life, being ‘much straightened in Time for the Settlement of this Things that concern both himself and his Estate’. A further request on 24 December 1644 found opposition in the House of Commons, led by Oliver Cromwell. But, nevertheless, Christmas spirit won out and a further delay was granted. Emboldened by this favour, four days later, Hotham pleaded for mercy. The House of Lords was supportive, but in the House of Commons two military comrades went head-to-head; Sir Philip Stapleton argued in favour of sparing Hotham, but Oliver Cromwell had the numbers behind him and carried the day – 65 votes to 55. One final plea for clemency was put to the Commons the day before the execution, but this time Cromwell romped home with a vast majority, defeating the motion by 94 votes to 46. Despite this, the House of Lords went ahead and ordered a delay to proceedings, prompting the House of Commons to fire off a warning to the Lieutenant of the Tower. Any reprieve had to be authorised by both Houses. Father and son were left with a last hope that only one of them might go to the executioners block. On the day of the son’s execution – 1 January 1645 – the House of Commons resolved that ‘execution be done’ upon Sir John Hotham, according to the sentence and directions of martial law. This decree saw Sir John put to death the following day. It was a clear sign that the old order, which had led Parliament so far, was also finished. Present on the scaffold was the renowned preacher, Hugh Peter. In his last speech Hotham accepted some faults, such as ingratitude and temper, but steadfastly denied betraying Parliament. Eleven months after the two executions a form of clemency was granted to the Hotham family when Parliament lifted the sequestration of their estates. There was also a thawing of royal hostility from beyond the grave. Following the execution of King Charles I, the publication of Eikon Basilike – writings attributed to the king – made specific reference to Sir John Hotham’s demise. The king described his pity for Sir John, because ‘after he begun to have some inclinations towards a repentance for his sinne, and reparation of his duty to Me, he should be so unhappy as to fall into the hands of their justice, and not My mercy, who could as willingly have forgiven him’. The king went on to declare that Hotham had become a ’noticeable monument of unprosperous disloyalty’ leaving it to future generations to decide whether Hotham was ‘more infamous at Hull, or Tower Hill’. Written by Mark Turnbull, author of a new biography of King Charles I – ‘Charles I’s Private Life’. Including new evidence about his childhood, and the identity of his executioners, this is a more intimate focus on the man, rather than the monarch.

2 Comments

Mark Turnbull

9/9/2023 22:34:12

Thanks David, really pleased you enjoyed it!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed