|

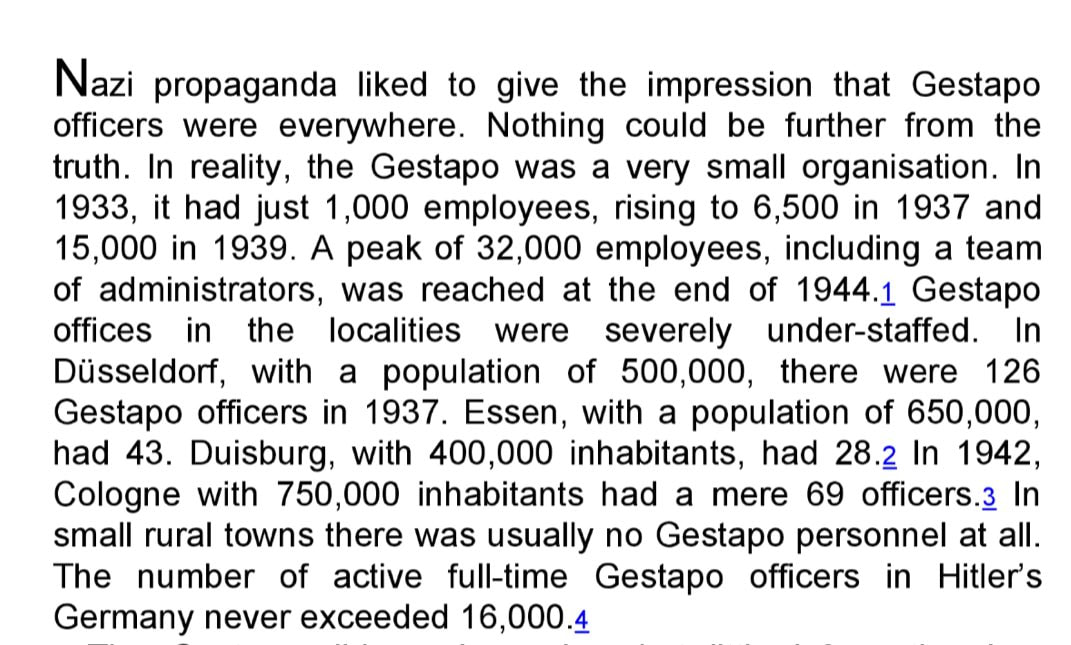

In the dark annals of history, one name stands out as the embodiment of fear and terror during Nazi Germany's reign—the Gestapo. While many perceive this secret police force as an all-encompassing behemoth, its quantitative size was smaller than we might initially think, supported by the scholarship of Frank McDonough. Here, we explore the three most significant aspects of the Gestapo's role, revealing its smaller-than-expected scale, but utter brutality beyond belief and comprehension. 1. The Myth of Omnipotence: Contrary to the common perception of an all-powerful Gestapo, Frank McDonough's research paints a different picture. The Gestapo was indeed a feared entity, but it was a much smaller organization than many believe. In 1939, it had just 7,000 full-time employees. Its influence, however, extended far beyond its numbers, primarily due to its vast network of civilian informants, which numbered around two million. This network, fueled by fear and incentives, effectively turned the population into unwitting agents of surveillance. 2. The Chamber of Horrors: Within the Gestapo's infamous interrogation chambers, victims faced unimaginable brutality. Frank McDonough's scholarship highlights the stark contrast between the small number of Gestapo agents and their extensive reach. These interrogators, armed with ruthless tactics, subjected prisoners to physical and psychological torment. In the cells of the Gestapo, you were treated like a thing, not a human being. The goal was to extract information, break spirits, and ensure compliance with the Nazi regime. 3. Complicity in the Holocaust: One of the darkest aspects of the Gestapo's role was its complicity in the Holocaust. Despite its smaller size, the Gestapo played a pivotal part in the arrest and deportation of countless innocent individuals. Reinhard Heydrich, a high-ranking SS official, insisted that Europe would be combed through from west to east. This directive set in motion the mass arrests, with the Gestapo at the forefront. The chilling statistics speak volumes—approximately six million Jews lost their lives, revealing the staggering impact of the Gestapo's involvement in this horrifying chapter of history. As we delve into the Gestapo's role in Nazi Germany, Frank McDonough's scholarship reminds us that power isn't always synonymous with size. The Gestapo, though smaller in number, wielded immense influence through its network of informants and ruthlessly efficient tactics. Its role in the Holocaust serves as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of unchecked power. In confronting this history, we must strive to remember the victims and prevent such atrocities from ever happening again. Written by VH Guest Blogger Ayesha Gill.

0 Comments

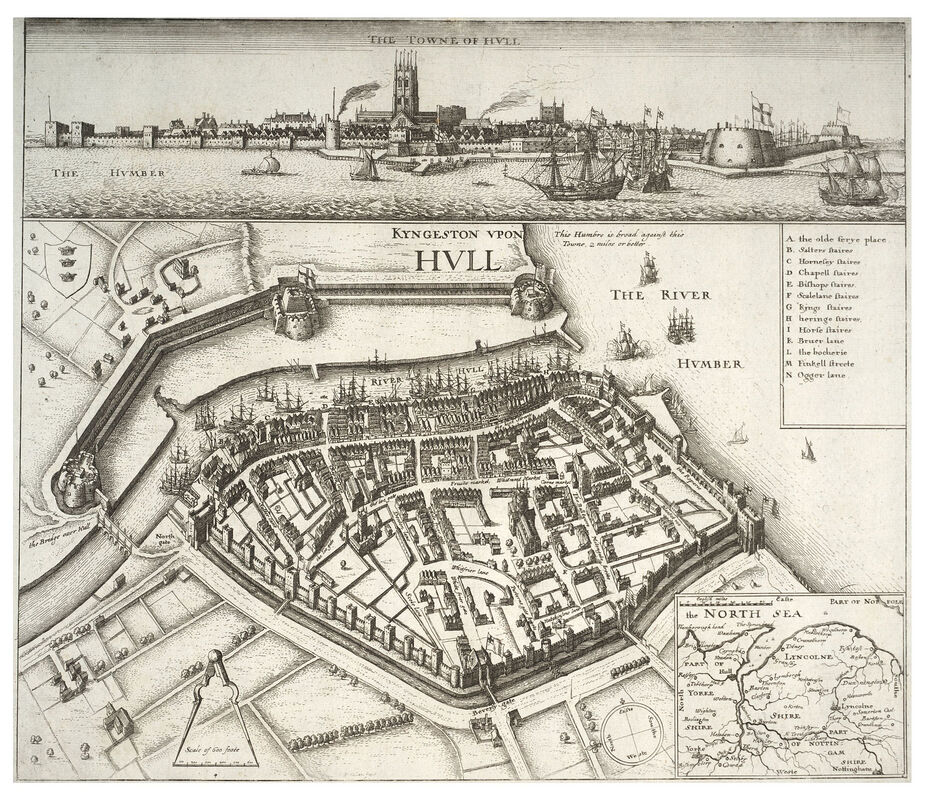

The English Civil War, fought between King Charles I and his Parliament, throw up many a strange story. One among them concerns the Hotham family. Parliamentarians, their loyalty was not always reliable, and Oliver Cromwell himself lost patience. On 1 January 1645, Captain John Hotham, having played loose with his loyalties in the wars that engulfed all three kingdoms of Britain, faced his end at the Tower of London. His proposal to pay Parliament £10,000 to commute his sentence to banishment had been declined, therefore supportively flanked by his brothers, he was put to death by the severing of his head from his body. The following day his father, Sir John, followed him to the block. In the months prior to the outbreak of civil war in England, the momentous actions of father and son delivered a port full of munitions to the parliamentarian cause. They went head-to-head with the king himself; an action that should have seen the Hotham’s wedded to Parliament for ever more. But within one year, that union became strained, for the Hotham’s loved their own status and standing more than either faction. The proud family rapidly fell from the grand pedestal upon which they had perched and managed to end up being mistrusted by both King Charles and Parliament. More especially, they incurred the wrath of Oliver Cromwell. 381 years ago, in January 1642, Parliament ordered Sir John Hotham to take control of Hull. Accordingly, his son led some troops to the town and then seized it – though this action was not borne from pure conviction to Parliament’s cause. Sir John, a one-time Governor of hull, had been dismissed from that post by the king in 1639. The spurned Hothams had coveted the return of this position ever since. Parliament, for their part, needed the town and its vital magazine and both parties became uneasy bedfellows. One of the strongest fortress towns in England was thus delivered to Parliament, along with an arsenal of weapons for 20,000 men, 7000 barrels of gunpowder and 120 pieces of ordnance. In gratitude to Sir John, Parliament appointed him Governor of Hull, a role that would bring infamy. Three months later, on 22 April 1642, Sir John received two surprise visitors; the king’s son, the 9-year-old Duke of York, and his nephew, the Elector Palatine. He reluctantly admitted them into the town. The next day – Saint George’s Day – Sir John’s own chivalry was tested when word reached him that King Charles I was now on his way. It was to be an epic showdown. Hull wasn’t big enough for both the king and Governor Hotham, and when His Majesty arrived, he found the gates already closed. As Sir John stood on the walls looking down upon the royal party, both his allegiance and that of Parliament were put to the ultimate test. This was personal. Parliament’s profession that it was opposing the king’s ‘evil counsellors’ and not the king himself, was cast into doubt. King Charles demanded entry. Hotham apologetically refused. Hull’s outer ditch, angled bastions, earthworks and the 25 towers atop its mediaeval walls seemed to reinforce this decision. The rasps of a royal trumpeter pronounced Hotham a traitor and some of the king’s men called out for the townsfolk to throw the governor from the walls. But nobody moved. Check-mated, the humiliated king finally withdrew. He wrote to Parliament demanding that justice be ‘exemplarily inflicted’ upon Sir John and specifically found it unforgiveable that Hotham delayed releasing his son and nephew until after further negotiation. Nearly four centuries later, this momentous event is regularly given as the unofficial start of the civil war in England. A further unexpected visitor arrived in June 1642, when a small ketch was captured, and a supposedly seasick Frenchman taken into custody at Hull. When brought before Sir John, the prisoner turned out to be none other than the king’s meddler-in-chief, Lord George Digby. The hapless Digby, with his golden locks and silver tongue, managed to secure a tacit agreement from Sir John to hand over Hull to the king. For the preservation of the governor’s honour, the monarch was to come in person and besiege the town. But Parliament’s suspicions were soon aroused, and the iron-willed Sir John Meldrum was posted to Hull to bolster Hotham’s backbone. Therefore, when the royal army did appear, digging trenches, flooding fields and raising batteries, the town remained defiant, and the king withdrew empty handed for a second time. Despite their expectations for preferment with Parliament, the wealthy and influential Hotham dominance of the region was rivalled by another Parliamentarian duo; that of Lord Fairfax and his son, Sir Thomas. It was Lord Fairfax who secured Parliament’s commission as commander in Yorkshire, but it would take more than a slip of paper to bring the Hothams into line, and they constantly disobeyed Fairfax to the detriment of the cause. The Hothams were not happy playing second fiddle to anyone on their home ground. By December 1642, young Captain Hotham was spilling his guts in letter after letter to the king’s northern general, the Earl of Newcastle. When Queen Henrietta Maria landed at Bridlington in February 1643, the captain met her on the pretext of arranging an exchange of prisoners. The Hothams did little to prevent the Queen’s march to York, along with the stash of arms, ammunition and money she’d gathered for her husband’s cause. Captain Hotham, in one of his indiscreet letters to Lord Newcastle, instead ventured that he had been so badly treated by Parliament that ‘no man can think my honour or honesty is further engaged to serve them’. Though in another he wrote of the violent and ill-conditioned officers in the king’s army and judged that he could not serve under any of them should he defect. By mid 1643, Captain Hotham’s indiscretions had made him many enemies; from John Hutchinson (Governor of Nottingham) to Oliver Cromwell, with whom the Hothams had also refused to co-operate militarily. As such, suspicions became ever more heightened. On 18 June 1643, Hutchinson finally arrested the younger Hotham. The captain fired off a letter to the queen, inviting her to rescue him, but promptly managed to escape and fled to Lincoln. He was recaptured soon enough and sent to London. During his time at Hull, Sir John Hotham had spoken out against Oliver Cromwell’s promotion of common men to officer rank. The headstrong Hotham had even threatened to fire on Cromwell’s men if they strayed into his territory. He’d also disobeyed Parliament’s Yorkshire commander, Lord Fairfax, causing a complaint to be lodged. Despite all of this, the one person who had steadfastly supported Sir John was Parliament’s Lord General, the Earl of Essex. But with his son imprisoned, time ran out for Sir John. He was forced to flee Hull, being fired at by his own garrison as he left. After being captured by his own cousin and then attempting an escape, it was said that he was clubbed from his horse by a musketeer and left with a black eye. When brought to the bar of the House of Commons to account for his actions, Sir John fell to tears. A trial was unavoidable. He found himself once again ensconced within a parliamentarian fortress; this time, however, it was the Tower of London. There both father and son languished. Four months passed. In October 1643, Lord General Essex intervened. He recommended that some of his officers try Sir John, but Parliament refused, instead desiring a full court martial. Essex then attempted to set the date of the trial as 8 December 1643, but he was again overruled. Nothing more was done for six months, and Sir John used his time in the Tower to pen a defence of his actions. Parliament granted him an allowance of five pounds per week, along with three pounds for his son, all paid from his estates; pocket money, which they must have found particularly galling. Sir John’s father-in-law unsuccessfully petitioned Parliament in June 1644, calling either for his trial or release. As the tide of war turned, so did the Hothams’ fortunes. Following the Battle of Marston Moor, 2 July 1644, royalist correspondence was captured which proved the Hothams had been in contact with the royalists. This was precisely what Parliament had been waiting for. The trial of father and son now proceeded apace, chaired by Sir William Waller. Sir John asked to sit during proceedings on account of being lame – his defence was quickly judged to be equally so. The argument that he only negotiated with the royalist Earl of Newcastle to buy time for Hull was dubious. He persisted, claiming that this was a tactic employed in the Thirty Years War, of which he was a veteran. The behaviour of father and son had doomed them. At this time, Lord General Essex’s influence was also on the wane, and he would soon be forced to step down. A new order was being ushered in; one which had no truck with the Hothams. Lord Ferdinando Fairfax, Sir John’s rival, was given the Hotham’s money, plate and goods. It was at this juncture that Lieutenant-General Oliver Cromwell steooed forward to extract his vengeance. Professor Ronal Hutton recently wrote that Cromwell was not to be sated in his pursuit of personal opponents within his own side, including the Hothams, who would be hounded to their deaths. Certainly, the House of Commons’ records bear this out. On 11 December 1644, Lady Hotham’s petition for clemency was reluctantly dismissed by a wavering House of Lords. It was, after all, a period where many moderate peers and MP’s felt threatened by the emerging dominance of men such as Oliver Cromwell. The Hothams fates seemed indicative of the factional infighting that had broken out at the heart of Parliament. On 14 December 1644, Sir John successfully petitioned Parliament for an extension of his life, being ‘much straightened in Time for the Settlement of this Things that concern both himself and his Estate’. A further request on 24 December 1644 found opposition in the House of Commons, led by Oliver Cromwell. But, nevertheless, Christmas spirit won out and a further delay was granted. Emboldened by this favour, four days later, Hotham pleaded for mercy. The House of Lords was supportive, but in the House of Commons two military comrades went head-to-head; Sir Philip Stapleton argued in favour of sparing Hotham, but Oliver Cromwell had the numbers behind him and carried the day – 65 votes to 55. One final plea for clemency was put to the Commons the day before the execution, but this time Cromwell romped home with a vast majority, defeating the motion by 94 votes to 46. Despite this, the House of Lords went ahead and ordered a delay to proceedings, prompting the House of Commons to fire off a warning to the Lieutenant of the Tower. Any reprieve had to be authorised by both Houses. Father and son were left with a last hope that only one of them might go to the executioners block. On the day of the son’s execution – 1 January 1645 – the House of Commons resolved that ‘execution be done’ upon Sir John Hotham, according to the sentence and directions of martial law. This decree saw Sir John put to death the following day. It was a clear sign that the old order, which had led Parliament so far, was also finished. Present on the scaffold was the renowned preacher, Hugh Peter. In his last speech Hotham accepted some faults, such as ingratitude and temper, but steadfastly denied betraying Parliament. Eleven months after the two executions a form of clemency was granted to the Hotham family when Parliament lifted the sequestration of their estates. There was also a thawing of royal hostility from beyond the grave. Following the execution of King Charles I, the publication of Eikon Basilike – writings attributed to the king – made specific reference to Sir John Hotham’s demise. The king described his pity for Sir John, because ‘after he begun to have some inclinations towards a repentance for his sinne, and reparation of his duty to Me, he should be so unhappy as to fall into the hands of their justice, and not My mercy, who could as willingly have forgiven him’. The king went on to declare that Hotham had become a ’noticeable monument of unprosperous disloyalty’ leaving it to future generations to decide whether Hotham was ‘more infamous at Hull, or Tower Hill’. Written by Mark Turnbull, author of a new biography of King Charles I – ‘Charles I’s Private Life’. Including new evidence about his childhood, and the identity of his executioners, this is a more intimate focus on the man, rather than the monarch.

Intrigue, deception, and power struggles - the English Civil War was a canvas painted with the bold strokes of history. As we embark on a journey through the annals of time, let us untangle the web of factors that ignited this momentous conflict. Join us as we delve into the witty tapestry of events that paved the way for a war that shook the very foundations of England.

The Royal Clash - A Game of Thrones Unfolds: Step into the court of Charles I, the enigmatic monarch whose longing for absolute power danced with the principles of parliamentary sovereignty. Clashing with a defiant Parliament, the sparks of discord began to ignite. While Charles believed in the divine right of kings, the Parliament was eager to safeguard the rights of the people. Thus, a riveting game of thrones unfolded, with each side vying for supremacy over the other. The Taxing Quandary - When Coins Clash: Ah, taxes - the age-old bone of contention! The English Civil War was no exception. The Stuart kings were all too fond of taxing the masses to fund their extravagant lifestyles and foreign wars. Alas, the Parliament and the common folk were left with empty purses and grumbling bellies. The Pilgrims and Puritans were displeased, for they believed that a king's coffers should be a trifle lighter when it came to the people's coffers. Religious Wrangling - Faith's Friction: When it comes to religious fervor, there's no shortage in England's past. The English Civil War had a healthy dose of religious wrangling. The Puritans, with their stern faces and disapproval of frivolity, sought to cleanse the Church of England of its perceived impurities. Meanwhile, Charles I leaned towards the ritual and pageantry of the High Church, leading to an irreconcilable clash of beliefs. A storm of religious zealotry brewed, setting the stage for a holy collision. Statistics Speak - A Royal Recipe for Rebellion: Oh, numbers, those unfeeling but revealing friends! Let's break it down with some cold, hard facts. By the mid-17th century, taxes had skyrocketed, pushing the English population to the brink. The Crown's share of the national income surged from 1.5% in 1603 to a staggering 10% in 1630. As the pressure of taxation weighed heavy on the people's shoulders, it's no surprise that rebellion began to simmer beneath the surface. The Final Straw - Ship Money's Sigh: Enter the villain of the tale - Ship Money! This egregious tax imposed by Charles I on coastal towns to fund his naval exploits left the masses seething. What could be more exasperating than paying for a royal fleet while having no say in the matter? The Parliament had reached its limit, and Charles' authority now seemed more arbitrary than divine. As we unravel the threads of history, we find that the English Civil War was a clash of wills, ideologies, and ambitions. It was the convergence of political intrigue, economic woes, religious fervor, and an insatiable hunger for power that culminated in one of the most significant chapters in England's history. This chapter reminds us that even the grandest of tapestries can fray when the forces of change and resistance entwine. So, let us raise our glasses to this chaotic yet captivating era - the English Civil War - a time when history took center stage, and the fate of a nation hung in the balance. Written by Versus History Guest Blogger Madeleine Adams-Jones. Madeleine is currently writing her first book on the role of religion in driving the English Civil War. The Starting Point ... The endless complaint about school history is that it is all just Tudors and Nazis. The school history curriculum is far broader than that. Yet, for those studying modern history GCSE, it does remain somewhat of an inaccurate truism when studying the 1920’s and 30’s that it is really just the story of the rise of Hitler as the main cause of WWII. Yes, Hitler did invade Poland in 1939, but to focus on the rise of Hitler is to vastly oversimplify a global slide towards conflict in the 1920’s and ‘30’s. Britain and France faced aggression not only from Germany but also Italy and Japan, and these huge Empires also faced rapidly growing internal discontent as well as worrying about the threat of Communist Russia. Understanding the wider global problems that Britain and France had in maintain control on their Empires from growing nationalist movements helps to explain why the conflict that emerged really was a ‘World War’ and also why British and French leaders were so slow to spot the threat they faced from Germany when they faced so many concerns from inside and outside their Empires. India For the leading politicians in the British Empire in the 1930’s Indian nationalists like Gandhi ere often seen as more of a threat than Hitler. Hundreds of thousands of Indians had fought for the Empire during WWI and the British Government stated that it supported progressive realisation of responsible government in India as part of the British Empire. Yet Britain proved reluctant to allow Indians any real autonomy, even though by 1931 the Indian Congress had the aim of purna swaraj – total independence. This was something that the British government simply could not allow given the economic and political significance of this ‘jewel in the crown’ of their Empire. It is not surprising then that there was growing discontent in India in this period. To give an example of how hindsight has changed the historical perspective students studying this period will see one of the key moments of 1935 as Hitler’s announcement of the rearmament of Germany. This was a critical unpicking of the Treaty of Versailles and marked the start of the growth in German’s military power. Yet in Britain at the time the press was far more alarmed with growing Indian nationalism. During that year there was particular opposition from many Conservatives in Britain objecting to the passing of the Government of India Act which increased the franchise for Indians and gave more control over domestic politics to Indian provincial governments. This led to the formation in Britain of the India Defence League, with Winston Churchill and Rudyard Kipling among its supporters. Churchill famously said that, ‘England, without her Empire in India, ceases to be a Great Power.’ Headlines in the Daily Mail warned of bloodshed in India if the wise rule of Britain was removed. Understanding the preoccupation of Britain with India helps to explain why so many people simply weren’t that interested in what was happening in Germany at the time. Gandhi, the leading Hindu nationalist, was famed for his dedication to non-violent protest, but this strategy proved to be an inspiration for nationalists in India and many others round the world. One Guardian correspondent wrote that, ‘To face the lathi (the steel-tipped cane of the British) charges became a point of honour and in a spirit of martyrdom volunteers went out in hundreds to be beaten’ and throughout the 1930’s one of the British governments most pressing concern was the question of how to retain control of its wealthiest and largest colony – not how to stop Hitler retaking land lost under the Treaty of Versailles. The USSR Another ‘big news story’ which is often kept as a side-note to British school histories of the 1920’s and 30’s is the start of Stalinist rule in Russia and the vast death toll that this created. Superficially Stalin allowed democracy, instituting a new ‘Constitution for the Soviet Union in 1936 that allowed elections every four years. Yet this was very much just a veneer for a society that still only allowed one political party, and Stalin entrenched his hold on power through the purging of millions of people who he deemed opponents through his secret police, the NKVD, in what became known as ‘The Great Terror.’ Many millions more died through Stalin’s police of Collectivisation where the peasantry were forced to unite their farms into large collectives to make them more efficient. Opposition to this movement led to falling production and destruction of crops by protesting farmers, and through a combination of famine and political executions it is estimated that around five million people died in Ukraine in this period, and over thirteen million across the whole of the Soviet Union. This was of particular geopolitical significance for two reasons. Firstly, as news of this bloodshed slowly filtered through to the west, leaders like Chamberlain became increasingly nervous about the prospect of an alliance with Stalin as a way of keeping German expansionism in check. Secondly, with around 90% of the Soviet Union’s top officers being purged in this period Stalin had left his own military dangerously weak, making him far less confident about the prospect of any sort of conflict. British opinion polls from the summer of 1939 showed that 84% wanted Britain, France and Russia to enter into a full military alliance, but in March of that year Chamberlain had already privately stated that: I have no belief in her ability to maintain an effective offensive, even if she wanted to. And I distrust her motives, which seem to me to have little connection with our ideas of liberty and to be concerned only with getting everyone else by the ears. Chamberlain was not alone in his fears, and a correspondent for the Manchester Guardian in March 1939 wrote that ‘Altogether, the terror in Russia is such that persons living even under the Nazi terror could hardly conceive of such a thing’ although even he admitted that ‘we cannot afford to be particular about our allies.’ All this meant that when Chamberlain did finally open negotiations with Russia he did not even send a senior minister to do this, and in his turn, Stalin made a speech stating the doing deals with fascist regimes was no worse than doing the same with liberal democracies. He saw how reluctant Britain and France were to use military force themselves in their many attempts to appease Hitler’s ambitions, and it is therefore unsurprising that Stalin was negotiating in secret with Germany from January 1939, and that he ended up doing a deal with Hitler as the Nazi-Soviet Pact signed in August. To conclude ...

As these two case studies show, the road to war in the 1930’s was a complex interplay of many different factors. Having a focus purely on Hitler and Nazism as the cause of war can downplay these other issues, and this can be a particular problem for a period which is so often used as a comparison to our own times. Charges of appeasement are regularly thrown at political leaders in comparing them to the people who ‘failed to stop Hitler’. It could be that we learn more useful lessons by understanding the incredibly complex scene of that decade where western leaders had to balance competing threats, as well as the reality that many people around the world themselves saw the influence and rule of these western powers as their biggest threat. Written by Luke Ramsden FRSA. Luke is the Señor Deputy Headmaster at St Benedict's School in London, UK. Luke read History at Oxford and is an award winning educational leader. Introduction:

The history of Germany in the early 20th century is marked by the rise of the Sturmabteilung (SA), commonly known as the Brownshirts. This paramilitary organization played a pivotal role in Adolf Hitler's ascension to power and the subsequent consolidation of Nazi control over Germany. To comprehend the significance of the SA, it is essential to explore their origins, tactics, and the profound impact they had on German society. This article will provide a comprehensive analysis, incorporating quotes from historians, as well as statistics and factual evidence, to shed light on this dark chapter in history. Origins and Purpose: Founded in 1920, the SA initially served as a protection force for the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). Driven by radical political ideology, the Brownshirts aimed to intimidate and suppress political opponents, particularly left-wing factions. The SA provided the muscle for the Nazis, streetfighters who sought to establish their dominance through violence and intimidation. Political Violence and Street Battles: A defining characteristic of the SA was their involvement in political violence and street battles with rival groups. Engaging in brutal clashes with communists, socialists, and Jews, the Brownshirts created an atmosphere of fear and terror. According to historical records, these confrontations often resulted in severe beatings and public humiliations. The SA's violent tactics were aimed at spreading fear and establishing Nazi supremacy. The Brownshirts were notorious for their street brawls. During the elections of 1932, political violence in Germany resulted in the deaths of 431 individuals, with the SA playing a significant role in perpetrating these acts. Path to Power: As Hitler's personal paramilitary force, the SA played a crucial role in the Nazis' rise to power. Their public displays of power, organized rallies, parades, and torchlit processions left an indelible impression on the German public. At its peak in 1933, the SA had approximately 2.5 million members, making it one of the largest paramilitary organizations in history. This staggering number underscores the SA's influence and ability to mobilize a considerable force in support of Nazi objectives. The SA's organized rallies, parades, and torchlit processions to create a spectacle of power. Challenges and Internal Struggles: The SA's rapid growth and increasingly radical tendencies created internal tensions within the Nazi hierarchy. Hitler's decision to consolidate power and establish the Schutzstaffel (SS) as a rival organization led to a power struggle between the two groups. The Night of the Long Knives in 1934 witnessed Hitler's ruthless suppression of the SA, resulting in the execution of several SA leaders. This event marked a turning point as the SS emerged as the dominant force within the Nazi apparatus. The SA's influence and power were significantly curtailed thereafter. The Night of the Long Knives witnessed Hitler's ruthless suppression of the SA. Impact on German Society: The SA's role extended beyond street violence; they actively participated in the implementation of Nazi policies, including the persecution of Jews and other targeted groups. Statistics and factual evidence attest to their involvement in enforcing anti-Semitic policies. During Kristallnacht in 1938, the SA played a significant role in the destruction of synagogues and Jewish businesses. This violent pogrom resulted in the arrest and deportation of thousands of Jews. During this pogrom, around 267 synagogues were destroyed, and approximately 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. The SA's actions, driven by their ideological fervor, contributed to the gradual erosion of civil liberties and the establishment of the totalitarian Nazi state. Conclusion: The SA, or Brownshirts, played a crucial role in Adolf Hitler's rise to power and the establishment of Nazi control over Germany. They served as Hitler's loyal enforcers, spreading fear and exerting dominance through violence and intimidation. Though eventually eclipsed by the SS, the SA's impact on German society was profound. As we reflect on this dark chapter in history, it serves as a reminder of the dangers of extremist ideologies and the destructive potential of paramilitary organizations. Written by VH Guest Blogger Ayesha Gill. The American national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner," is a symbol of national pride and patriotism. But do you know the story behind its creation? Let's take a trip down memory lane to explore the origins of this iconic song.

It all began during the War of 1812, when British forces were attacking the city of Baltimore. Francis Scott Key, a lawyer and amateur poet, witnessed the battle from a British ship where he had gone to negotiate the release of an American prisoner. As the battle raged on, Key saw the American flag still flying over Fort McHenry and was inspired to write a poem about the experience. "The rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air, gave proof through the night that our flag was still there," Key wrote in his poem. It was later set to the tune of a popular British song, "To Anacreon in Heaven," and became known as "The Star-Spangled Banner." The song was an instant hit, and by the end of the 19th century, it was played at public events across the country. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson officially recognized it as the national anthem, and it has been a staple of American culture ever since. But did you know that the original poem was actually four stanzas long, and we only sing the first one? The other three stanzas are rarely performed or even known by most Americans. As historian Marc Ferris points out, "The Star-Spangled Banner" is more than just a song – it's a symbol of American resilience and perseverance in the face of adversity. "It's a reminder that we have overcome great challenges in the past and will continue to do so in the future," he says. Today, "The Star-Spangled Banner" is still sung at sporting events, political rallies, and other national gatherings. It may not be everyone's favorite song, but it remains a powerful representation of the American spirit. As Key himself wrote in the final stanza of his poem, "O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave, O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave?" It's a question we still ask ourselves today – and the answer, of course, is a resounding yes. Written by Versus History Guest Blogger Emilia Urquhart. So, England has a new Queen-Consort in Queen Camilla. History tends to overlook the consort, focusing its attention (for better or worse!) on the hereditary monarch. However, while there have been many performing the role of Consort - some, like Anne Boleyn losing their heads in the process - there is (at least!) one successful example for Camilla to draw inspiration from. Queen-Consort Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was a remarkable woman who left an indelible mark on England during her reign as queen-consort from 1761 to 1818. Her legacy as a patron of the arts, philanthropist, and supporter of education lives on to this day. Given that she arrived in England for the very first time as wife to the newly coronated King George III from Central Europe, her achievements are perhaps all the more remarkable. Even more so, perhaps, when we consider the ill-fated arranged marriage just over two hundred years previously between another King of England (Henry VIII) and Anne of Cleves, who, like Charlotte, could speak little - if any - English. Like Anne, Charlotte originated from Europe and had never stepped foot in England previously, arriving in England for the purpose of a Royal Marriage. With this in mind, we will explore some of the most notable achievements of Charlotte during her time as Queen of England. One of Charlotte's most significant accomplishments was her patronage of the arts. She was a passionate supporter of the Royal Academy of Arts and counted artists such as Joshua Reynolds and Johann Zoffany among her close friends. Reynolds painted numerous portraits of Charlotte, including one of her wearing a simple dress and no jewels, which became a sensation at the time. As art historian Elizabeth Einberg notes, "Charlotte's interest in art was genuine and lasting...she made a considerable contribution to the artistic culture of her day." In addition to her patronage of the arts, Charlotte was deeply committed to philanthropy and improving the lives of the less fortunate. She founded numerous organizations aimed at helping those in need, including the Royal Female Orphanage and the Royal General Lying-In Hospital. She also supported the establishment of schools for underprivileged children, including the Asylum for Female Orphans and the Foundling Hospital. As historian Flora Fraser notes, "Charlotte was the first queen to become actively involved in philanthropic work." Her philanthropic work left a lasting impact on society and helped to shape modern England.

Charlotte's commitment to education was also a significant part of her legacy. She was an advocate for the education of women and supported the establishment of schools and institutions for women's education, including the Queen's College in London. She also encouraged her daughters to pursue an education and provided them with a strong foundation in the arts and sciences. As her daughter Princess Sophia once said, "My mother was very much for the education of women, and she set us all an example in that respect." Finally, Charlotte was known for her strength and resilience in the face of adversity, including her husband's bouts of mental illness. During one of George III's episodes, Charlotte assumed the role of regent and provided steady leadership for the country. As historian Julia Baird notes, "Charlotte's steadfastness and courage during these years was crucial in maintaining stability and continuity in a time of great uncertainty." In conclusion, Queen-Consort Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz was a remarkable woman whose achievements as Queen of England continue to be celebrated to this day. Her patronage of the arts, philanthropy, and support for education left a lasting impact on society and helped to shape modern England. Camilla has strongly indicated that she shares Charlotte’s charitable ethos and dispositions. Charlotte’s strength and resilience in the face of adversity were an inspiration to all who knew her, and her legacy serves as a reminder of the power of leadership and dedication. Camilla will, we hope, emulate this and we wish her every success in the role. Written by Versus History Guest Blogger Ayesha Gill. During the early 19th century grave robbery became common practice due to the increased interest in medical science creating a demand amongst medical students for bodies to conduct medical research.

As historian Sarah Wise notes in her extensive study of the subject The Italian Boy in 1831 there were estimated to be around 800 medical students in London, Up until 1832 the only source of these bodies for medical studies were those of criminals hanged for murder. The number of bodies available to the students was far too low to accommodate their demand. Resurrection gangs were highly organised tight knit operators, networking in specific meeting places within travelling distance of medical schools, such as at the Bricklayers Arms public house on the Old Kent Road. For historians, how those caught in the act of grave robbery were dealt with by the courts sheds light on tensions between Victorian ‘laissez-faire’ economics and public morality. Resurrectionist gangs were despised amongst the general population, families of the deceased were left without closure, as their loved ones were taken and used without their consent. Additionally, the practice was dangerous as grave robbers often encountered angry mobs and were at risk of being caught and punished. Members of resurrectionist gangs would often scatter body parts around the homes of rival gangs to draw attention to them and arouse public hostility. However, despite this widespread public disdain, penal sentences for grave robbers were relatively light. In the eyes of the law, the dead human body did not belong to anyone and was not considered to be of material value. The maximum penalty was a fine or six months imprisonment. Cases were most likely to be tried as misdemeanours in a magistrate’s court and as a result very few records of court proceedings involving body snatching remain on public record. Resurrectionist gangs were careful not to take anything else from the grave to avoid more serious charges. In response to the growing problem of grave robbery, the Anatomy Act of 1832 was passed in the UK. The act allowed for the legal donation of bodies to medical schools and abolished the practice of using executed criminals as the only legal source of cadavers. It also allowed for the bodies of those who had died in workhouses to be used. While this put grave robbers out of business, disposing of the bodies of the poor in the same way as bodies of the hanged served to stigmatise poverty by equating the bodies of deceased paupers with the dead bodies of criminals in the public mind. Architectural historian, Professor James Stevens Curl’s research reveals that even though the business of grave robbery effectively ended in 1832 with the change in regulation, the repetition and fear surrounding the activities of the resurrectionist gangs lived on. Many families held onto corpses of relatives in their houses until they had decayed too far to be of interest to any anatomist. Furthermore for the multitude of the working population living on incomes just above workhouse poverty levels, a family bereavement posed serious economic difficulties. This also meant sanitary disposal of bodies would often have to be delayed until the bereaved raised the funds for a funeral. In conclusion the study of resurrection gangs and their activities can help historians shed light on changing Victorian attitudes towards death and memorial. The demand for cadavers for medical research led to the desecration of graves and the violation of the rights of the deceased and their families. While the Anatomy Act of 1832 helped to address the problem, it did not eliminate it. Further Reading Curl, J.S. (2004) The Victorian celebration of death. Stroud (Gloucester, England): Sutton. Wise, S. (2012) The Italian boy: Murder and grave-robbery in 1830s London. London: Vintage Digital. Written by Versus History Guest History Blogger Karl Brown (@MrBuddwing65). You can follow Karl on Twitter here. The Vietnam War was a long, costly, and divisive conflict that ended when the United States left in 1975. Despite America deploying over 500,000 troops and spending billions of dollars, they eventually withdrew in defeat. The Vietnam War was a contentious conflict that has been analyzed and debated by historians for decades. Many of these historians have identified specific factors that contributed to the U.S.'s defeat in Vietnam.

Guest Versus History contributor, Shehab Abdullah British pubs and bars have been an essential part of the country's social and cultural life for centuries. However, over the past twenty years, there has been a significant decline in the number of pubs and bars in the UK. There are several reasons for this decline, ranging from economic factors to social changes. In this article, we will explore the five main reasons for the decline in British pubs and bars, citing precise statistics to support each reason.

Changing Drinking Habits One of the main reasons for the decline in British pubs and bars is changing drinking habits. According to a report by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), alcohol consumption in the UK has decreased by 16% since 2004. This decrease in alcohol consumption is attributed to a rise in health-consciousness, changing attitudes towards alcohol, and a shift towards non-alcoholic alternatives. High Taxes and Costs Another factor contributing to the decline of British pubs and bars is high taxes. The UK has some of the highest taxes on alcohol in Europe, with beer duty increasing by 60% over the past 17 years. According to the British Beer and Pub Association (BBPA), pubs pay 2.8% of all business rates, despite accounting for just 0.5% of the total UK economy. The high costs of energy and staff is also a significant issue facing many British businesses, including the beloved-pub. The rising price of real estate has also resulted in many pub-plots being sold off or repurposed to become homes, flats, nursing homes or knocked down altogether. Competition from Supermarkets Supermarkets selling alcohol at cheaper prices have also impacted the pub industry. According to a report by the Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA), beer sales in pubs fell by 7.3% between 2012 and 2017, while beer sales in supermarkets increased by 22%. The same report states that a third of pub closures are due to competition from supermarkets. Economic Recession The economic recession that began in 2008 also contributed to the decline in British pubs and bars. The recession led to a decline in disposable income, which affected the pub industry as people cut back on discretionary spending. According to the BBPA, there were 2,500 pub closures between 2008 and 2013. The devastating impact of the pandemic and the subsequent 'lockdowns' did nothing to assist the trade, harming the it still further when the situation was already precarious for many outlets. Social Changes Finally, social changes have also played a role in the decline of British pubs and bars. The rise of online social networking and the availability of entertainment options at home have made going out to a pub or bar less appealing to younger generations. According to a report by the BBPA, 18 to 24-year-olds are visiting pubs less often, with 29% saying they go to the pub less than once a month. In conclusion, the decline in British pubs and bars is a complex issue, with multiple factors contributing to the decline. Changing drinking habits, high taxes, competition from supermarkets, economic recession, and social changes have all played a role in the decline of the pub industry. While the situation is challenging, some pubs and bars are adapting by offering different services such as food or hosting events to attract customers. The growth of craft ale and 'gin culture' have bee positive for the trade in recent years, allowing enterprising and responsive pubs to develop a new following. Ultimately, the long term future of British pubs and bars will depend on their ability to evolve and meet the changing needs and preferences of customers. |

Categories

All

Archives

March 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed